by Timothy Robson

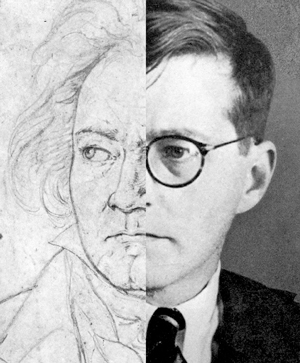

The program book featured specially written essays by Welser-Möst and composer/journalist Frank J. Oteri on the relationship of Beethoven’s and Shostakovich’s music to politics. For Beethoven, especially composing the third, fourth and fifth symphonies following the French revolution and under the philosophy of the Enlightenment; and for Shostokovich, enduring the Stalinist period of World War II and the grim Soviet era 1950s following Stalin’s death.

Beethoven’s was a period of social upheaval and political protest; Shostakovich lived in an era of political repression, where a statement against the regime likely would have dire consequences. Both composers expressed their political views through their music: Beethoven the concept of the freedom of all humankind; Shostokovich the idea of political protest hidden in secret messages within his music. The appreciation of these two great symphonies is not dependent on awareness of their context—even when performed together; however, the written commentary did enhance the experience.

How does one approach the performance of the musical work that begins with the most famous four notes in all of music? “Beethoven’s Fifth” has been played in every conceivable way (as well as some that are likely inconceivable); is it necessary for a conductor to try to find something new in this timeless masterpiece? Franz Welser-Möst did not strive for the unusual or bizarre; he infused this performance, especially the famous first movement, with tension and urgency, with tempi that were brisk but not rushed. There were wide dynamic ranges, from the most delicate quiet passages to thunderous climaxes.

The second movement, a set of variations, was much more relaxed. The third movement was delicate, yet mysterious, ending with the huge crescendo that is the transition to the glorious, full-blooded finale, with its striking use of piccolo at the end of the symphony, Beethoven’s first use of the instrument, and the extended cadence pounding home a glorious C major ending.

Shostokovich’s Symphony No. 10 was written beginning in about 1948 (perhaps even earlier), and was completed and announced in the months following Stalin’s death in 1953. The composer had been a target of the Soviet Politburo for the vague charge of “formalism,” which was vague enough to be difficult to defend against.

The symphony is highly self-referential, with a musical motif based on Shostakovich’s name (D – E-flat – C – B-natural, corresponding to the first initial of his name, and the first three letters of the German transliteration of his last name including “Es” (E-flat) and “H” (the German identification of B-natural). The motif forms the basis of the first movement, by far the longest of the four, and returns in the other movements.

The first movement opens with a growling unison melody in the double basses, and expands from there to a strident climax with trilling strings, brass fanfares and snare drum. The music fades away, only to be further developed. Solo piccolos end the bleak movement.

The second movement, a fierce scherzo-like allegro, was frantic, like a battle scene, that ends as suddenly as it begins. The third movement features solos from all of the principal wind players, later a prominent solo for horn. Out of nowhere Shostakovich inserts a snippet of a grotesque waltz, which disappears as quickly as it came.

The fourth movement is introduced by a sinuously chromatic oboe solo, a theme then taken up by the solo bassoon. The main part of the movement is marked “Allegro,” and is a huge development of the D – S – C – H theme, repeated unceasingly in many forms. The climax is glorious, and The Cleveland Orchestra’s performance was thrilling. But as with much of Shostakovich’s music, it was unsettling. Was Shostakovich being ironic or triumphal? It is an unknowable question.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 29, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.