by Kevin McLaughlin

The world premiere of Quinn Mason’s Portrait of Scheherazade, commissioned by the CSO, made for an appealing start. It’s always exciting to hear a piece for the first time, particularly so when it’s introduced by the composer. Speaking easily and plainly, Mason identified his purpose as depicting the person of Scheherazade (“who the lady was”) rather than refashioning the famous work by Rimsky-Korsakov.

Quinn’s Scheherazade (the lady) is a “loving” and attractive figure, represented by warm strings and a beguiling clarinet solo. By contrast, her strong will (she tells a different story every night for a thousand and one nights, for heaven’s sake) is conveyed by a “persistent theme” in the low strings, timpani, and tuba. After a pause, the work returns to the warm string chords, fading away too soon, leaving us (and the sultan, presumably) wanting more.

The Canadian pianist Sheng Cai is a sure rising star. With enormous technique and graceful control of rubatos and tempi, he reminds one of heavyweights such as Yefim Bronfman or Cai’s teacher at Juilliard, Gary Graffman. One could imagine what he might have done with a better-sounding piano (the one used on Sunday was inexplicably tinny, especially up high), but the gifts on display were remarkable. This was fine playing and a convincing case for more frequent performances of this easy-to-like concerto, Saint-Saëns’ fifth.

Known as “The Egyptian,” the work was a natural companion for the two Scheherazades — not only for its nickname but for the occasional exoticism (augmented scales in the second movement) and found melodies: a Nubian folksong, and an aria from the composer’s Samson et Dalila. Sheng Cai and the orchestra also paired well, agreeing on rubatos and a wonderful sense of rising tension in the toccata-like finale. Standing ovations were warranted, as was a tricky encore, Montreal-born composer André Mathieu’s Printemps Canadien.

A regional, if not national gem, Gerhardt Zimmermann showcased his usual sure hand in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade. Sitting to conduct, he demonstrated more control and flair than his more balletic peers. Where many are tempted to leap and step on the gas for excitement, Zimmermann kept tempi and temperature in check, achieving surety, not worry, from his players.

Scheherazade’s persona was enticing and resolute in the hands of concertmaster Konrad Kowal, whose tone radiated and shimmered in the hall. Indeed, this was an entire orchestra that knew exactly what it was doing. Soloists shone, especially the principal winds: clarinetist Georgiy Borisov, flutist Jenny Robinson, oboist Terry Orcutt, and bassoonist Todd Jelen, all outstanding. The brass made a glorious sound, even while portraying the menacing Sultan. And the fast tonguing by horns and trumpets was handled with such ease as to seem nonchalant. The music on this night charmed and enchanted, and may well have done so for a thousand and one more.

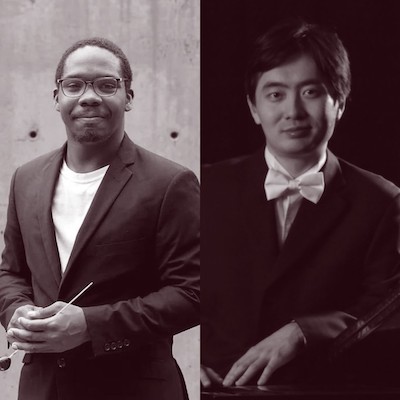

Pictured: Quinn Mason and Sheng Cai

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 31, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article