by Mike Telin

The second edition of the Festival, which runs September 6-9, will include screenings of five films, each with live accompanying music, at three locations around Cleveland.

Laurance, a visiting associate professor of musicology at Oberlin Conservatory, noted that Colorado-based Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra will be returning, and the partnership with the Cinematheque at the Cleveland Institute of Art continues as well.

“This year we’re bringing in noted theater organist Clark Wilson, and the Western Reserve Theater Organ Society and Radio on the Lake Theater are new partnerships.” New venues include Masonic Auditorium and Cleveland Museum of Art. Click here for tickets and more information.

The Festival kicks off at 7:30 pm on Wednesday, September 6 at Masonic Auditorium with a screening of Harold Lloyd’s 1923 iconic film Safety Last! The screening will feature Clark Wilson performing on the mighty Wurlitzer. Wilson’s accompaniments will reflect the techniques and materials of the musical performances given in major picture palaces during the heyday of silent film.

In addition to his busy concert schedule, Wilson is a sought-after tonal consultant and finisher of theater and classical pipe organs, and has been involved with more than 100 organ installations throughout North America and England.

On Thursday the 7th at 7:30 pm at the Cleveland Institute of Art’s Cinematheque, Colorado’s Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra returns to Cleveland for the first of three Festival programs: The Mark of Zorro (1920).

There’s a double bill on Friday the 8th at 7:30 pm at Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gartner Auditorium: The Heart of Cleveland (1924) and Man with a Movie Camera (1929). The former chronicles a fictional family living on a Northeast Ohio farm with no electricity. A pilot en route to Cleveland makes an emergency landing in their field and invites the two farm children to the city to learn about electricity. The film was produced for the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company and is an opportunity to see aerial shots of the city during its industrial heyday.

The Heart of Cleveland was recently discovered at Cinecraft Productions in Ohio City, and was digitized and archived by the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware. The screening will feature a talk by Kevin Martin of the Hagley preservation team, who will give a background on the film, its discovery, and its restoration.

Directed by Dziga Vertov with cinematography by Mikhail Kaufman, the documentary Man with a Movie Camera presents a tour of Soviet urban life. While the film features footage from Moscow, most of it was filmed in present-day Ukraine.

Laurence said that Mont Alto’s Rodney Sauer deserves credit for the pairing of the two films. “He thought they would make a good double bill because in their own way, they’re both about the birth of the modern industrial city — but from very different perspectives. The Heart of Cleveland is very much an infomercial for the illuminating company, as opposed to Man with a Movie Camera, which is more of an artsy film that documents life in various Soviet cities.”

The Festival will conclude on Saturday the 9th at 7:30 pm at the Cinematheque with Lewis Milestone’s 1930 All Quiet on the Western Front. During the screening, Mont Alto’s music will be supplemented by sound effects created live by Cleveland’s own Radio on the Lake Theatre.

If you weren’t aware of the silent version of All Quiet on the Western Front, Laurance said that during the transition from silent to sound, it was common for studios to release two versions of a film. “The sound version was the one released in the States and the silent version was the one released abroad. They’re almost identical, except for supertitles, but I’m biased toward the silent version because in a way, it has more power with the live music.”

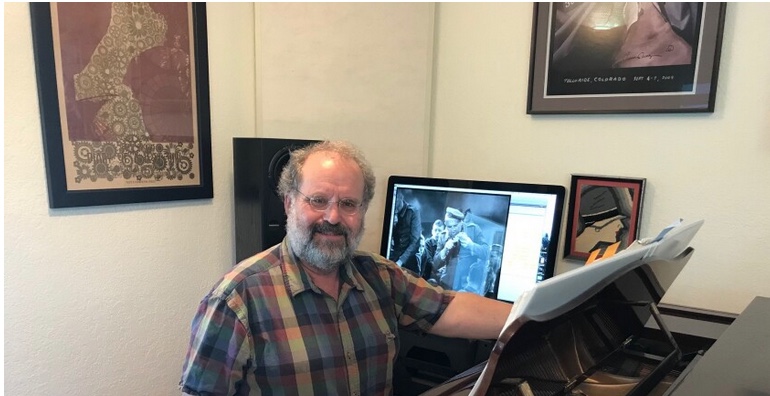

Prior to the 2022 Cleveland Silent Film Festival, Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra artistic director Rodney Sauer explained the process for preparing a silent film score, beginning with photoplay music. The following is an excerpt from our conversation.

So what is photoplay music? “It was called a whole bunch of things back in the day,” Sauer said during a telephone interview. “I didn’t invent the term but incidental music is a little more vague. There were other terms that were used but ‘photoplay music’ pegs it.”

“It’s important to know just how flexible this repertoire is,” Sauer said. “You can play it with any size orchestra. It was designed that way because it was a commercial business. You wouldn’t have a 40-piece orchestra in a small town, so what do you do? You use the same music, just simplify it.” Click here to access Sauer’s Photoplay Starter Kit.

How did Sauer, a pianist with a chemistry degree from Oberlin, discover photoplay music and come to form the Mont Alto Orchestra? “I discovered it when I was looking for dance music — I’ve always enjoyed playing for dancers,” he said.

His search led him to a collection of music housed at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “It turned out to be mostly silent film music that I had never heard of. Just the vastness of this repertoire, how big it was in America, and how it was completely forgotten, was like coming across a lost country.”

One thing led to another until Sauer found himself renting a movie and compiling a score. “It all went up from there,” he said. “I got a movie on 16 millimeter film from the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, rented an auditorium, and put on the show — it was a blast. Since then I think I’ve scored almost 150 movies.”

Sauer said that although more people are now scoring silent films, obtaining the material is still difficult. “Now that many of the collections are online it is getting easier,” he said. “The reason I’m coming to Ohio is that Emily and I are both interested in getting a new generation of musicians interested in this repertoire. And not just playing the music I’ve compiled — I want them to be able to put the scores together on their own.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 30, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article