by Mike Telin

On Saturday, May 25 at 7:00 pm at Rocky River Presbyterian Church, McGirr will join conductor Matthew Salvaggio and the Cleveland Repertory Orchestra in Elgar’s five-movement song cycle for mezzo-soprano and large orchestra. The program also includes Jessie Montgomery’s Overture and Barbara Harbach’s Symphony No. 10 (“Symphony for Ferguson”).

Harbach’s work pays tribute to the tenth anniversary of the civil unrest in Ferguson, Missouri after the killing of Michael Brown during the summer of 2014. In an email Salvaggio said, “Harbach was living and teaching in St. Louis at the time, and the piece takes music familiar to people living in Ferguson (like Wade in the Water and Chester) and transforms them into a powerful reflection on the events of that summer from the perspective of someone living in that community.” The concert is free. Click here for advance registration.

Back to the Elgar, McGirr and I continued our conversation by delving further into the piece, beginning with the poems that make up its text.

Kira McGirr: There are five different poets, but I see the poems following a journey as opposed to being just five different poems. I will give acknowledgement to the wonderful Elgar scholar Charles McGuire, who presents the idea that there’s a narrative through the five poems.

One part of that narrative is travel — each of the songs takes place in a different location.

The first, “Sea Slumber Song” by Roden Noel, takes place on the coast of Cornwall. The second is “In Haven (Capri)” by Caroline Alice Elgar, who was Elgar’s wife, and Capri is off the coast of Italy. The third is “Sabbath Morning at Sea” by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and you eventually end up in Australia with “Where Corals Lie” by Richard Garnett and “The Swimmer” by Adam Lindsay Gordon.

The second narrative idea is that of a metaphorical journey from childhood to old age.

The first movement is a sea mother singing to the child. You get the sense of a childlike fantasy — elf in land, elf in light.

The second movement is very much about naive and youthful love. And then it makes a transition and the narrator is a little older, a little wiser — they’re on a journey and fondly remembering friends at home.

The fourth movement is an older speaker, and as much as they love where they are, there’s also this immense desire to journey and explore the world.

And by the fifth movement you get to an even older, more mature person with a lot more lived experience. In the last line of text, the narrator desires to go where no light veers and no loved one remains — kind of this idea of into the infinite. I don’t think it’s death, but that the journey continues in life.

KM: It is, but in a different way than I’ve experienced before. It’s all very lyrical, but there’s a lot of text and it’s important to get that text across. There’s a large orchestra, so there’s a lot of power behind me. By the time you get to number five, you’ve been through a fair amount already. And five is the longest movement, so you need a lot of stamina. So yes, it’s demanding in that way. But again, it is written so well for the mezzo voice that it works.

MT: I am such a lover of English music of that period, and I know you are too. What attracts you to it?

KM: There’s a lushness about the music. I’ve always been really drawn to 19th-century vocal-instrumental works, whether it’s a larger orchestra like this one or a smaller ensemble. That was such an important kind of format at the end of the 19th century. It’s interesting that this piece isn’t more famous, because it really demonstrates everything that was popular during that period.

MT: This may be a little bit off track here, but I was reading that when it premiered in October of 1899 at the Norfolk and Norwich Festival, Clara Butt sang the premiere dressed as a mermaid. Do you have any special costume in store for the audience?

KM: I will not be covered in shimmering scales, and of course it’s so funny that her outfit is mostly what the press focused on. They said, ‘Oh, the music was great too but she was dressed like a mermaid, didn’t have a corset — wild and crazy.’ I believe that my choice of attire will not generate quite so much controversy, and hopefully the music will be first and foremost.

MT: Is there anything else you would like to tell me?

KM: It’s so exciting to be performing this piece. I just absolutely adore the songs and I love singing them.

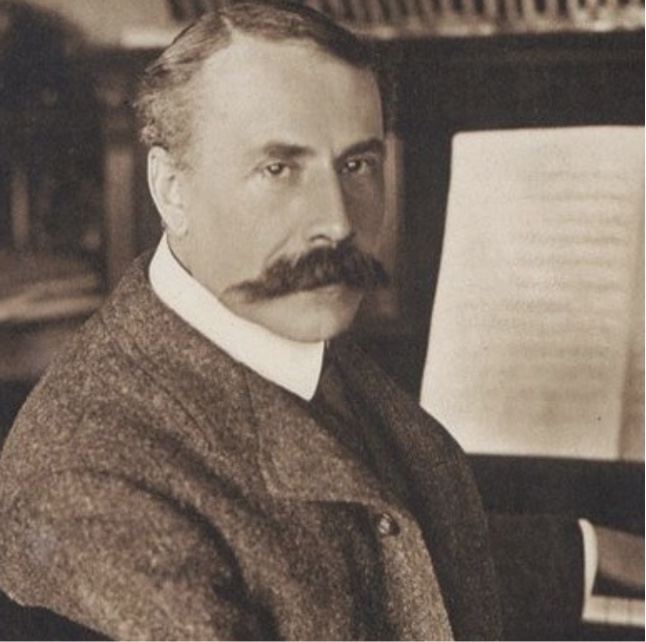

McGirr photo by Jennifer Manna.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 23, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article