by Mike Telin

George Szell made his first appearance as music director of The Cleveland Orchestra on October 17, 1946, opening the ensemble’s twenty-ninth season with Weber’s Oberon Overture, Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, Strauss’s Don Juan and Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony.

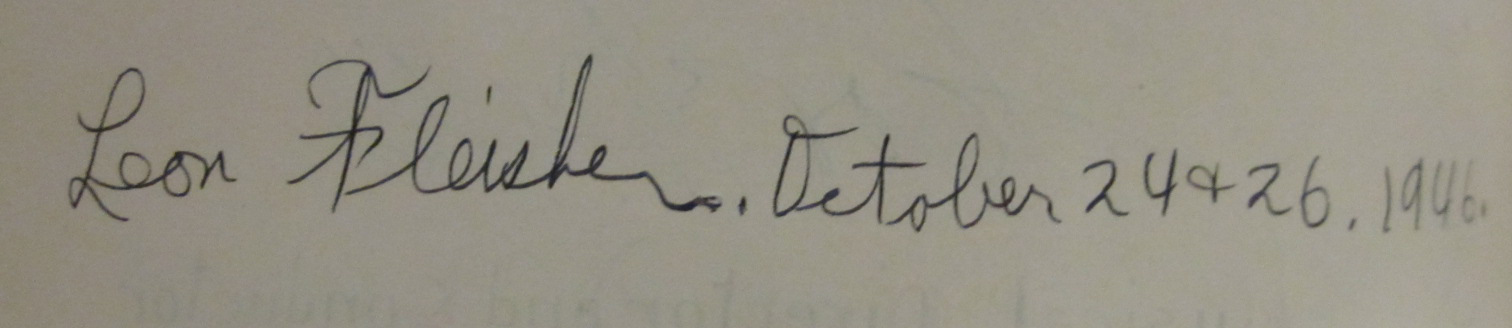

One week later, on October 24 and 26, Szell welcomed his first soloist to the stage when 18-year-old Leon Fleisher played the Schumann concerto with the orchestra on a program that included Brahms’s second symphony, Berlioz’s Roman Carnival Overture and Britten’s Three Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes.

On October 25, Plain Dealer critic Herbert Elwell wrote, “The second symphony program of the Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell last night at Severance Hall was another stimulating evening of vigorous and enjoyable music making to which the young American pianist, Leon Fleisher made a splendid contribution by his brilliant playing of the Schumann Concerto.”

Elwell went on to say, “No pianist could have been supplied with a more expressive or closely woven instrumental backdrop than that provided by Szell and it often seemed as though piano and orchestra were so intimately inter-related as to be one.”

That opening concert marked the beginning of what has become the longest relationship of any visiting artist with The Cleveland Orchestra. This weekend, on December 5, 6 and 7, Leon Fleischer returns to Severance Hall —this time as conductor — to lead the orchestra in Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture and in Beethoven’s second and third piano concertos. Pianist Jonathan Biss has agreed to replace Mitsuko Uchida, who has withdrawn due to a minor thumb injury.

Surely it entitles him to some kind of prize. Fleisher has logged 71 performances with the Orchestra as piano soloist, the last time in 2003 when he played Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand with David Zinman at Blossom. He appeared as guest conductor only once before, in January of 1978 at a West Side Concerts series performance by the Orchestra in Lakewood Civic Auditorium.

His discography with the Orchestra includes all five Beethoven concertos, both Brahms concertos, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Franck’s Symphonic Variations and Mozart’s 25th concerto as well as the concertos of Grieg and Schumann.

All of those recordings were in partnership with George Szell, with whom Fleisher had a special bond. “I don’t know if it was paternal or avuncular, whatever,” Fleisher said. “But I had an extraordinary kind of musical relationship with him. Not once in our career together, if you want to call it that, did he disagree with what I was doing with my interpretation. The background as I see it is that George Szell adored my teacher, Artur Schnabel, and I was kind of a shining young American with European gifts.”

As an early teenager, Fleisher first met Szell at a New Friends of Music concert series at Town Hall in New York that Schnabel helped create. The series was educational for the young pianist. He heard Bartók and his wife play the sonata for two pianos and percussion there as well as encountering Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire for the first time. “I burst out laughing because I had never heard Sprechtstimme before and it seemed to me like a kind of whooping, My mother had to take me out of the hall.”

Fleisher recalls his first impressions of Szell. “He was a very imposing gentleman in a black overcoat and black Homburg. I remember he strode over to Schnabel’s box and they embraced. Schnabel saw me sitting in the balcony and he beckoned me to come over and he introduced me.”

Szell invited Fleisher to play in Cleveland after collaborating with the young pianist the summer before at Ravinia. While Szell could be brutal with pianists — he once pushed Clifford Curzon off the bench and demonstrated how a passage should go — Michael Charry recalls in his recent biography of the conductor the very different first collaboration between Szell and Fleisher in Cleveland. “Szell told Fleisher that is was unnecessary to have a piano rehearsal before they rehearsed with the orchestra, saying, ‘I know how you play this. My orchestra is so trained as to whatever you do they will just follow.’”

All went swimmingly in Fleisher’s career until he suffered a major setback in 1965, withdrawing from The Cleveland Orchestra’s Soviet tour due to “a pulled tendon in his right hand,” as reported in the Plain Dealer on April 19.

Ironically, just two weeks before, Plain Dealer critic Robert Finn had written in a review of Mozart’s C-major concerto, K. 503, “Fleisher’s fingerwork was perfect, his rapport with Szell and the orchestra exemplary. If the Fleisher-Szell team works together like this on the coming Russian tour, the Russians will not soon forget it.”

Fleisher & Szell after a performance of Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, October 25, 1956 (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

Sound clip: Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini (Variation 18), Leon Fleisher with George Szell and The Cleveland Orchestra, October 25, 1956. (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/122928409?secret_token=s-NCFGD” params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

That concert proved to be Fleisher’s last appearance with George Szell. Later, the diagnosis of his hand problem was to be changed to focal dystonia, seemingly ending his career — at least as a two-handed pianist. Undaunted, Leon Fleisher relaunched his career with works like Ravel’s Concerto for the Left Hand and Prokofiev’s fourth concerto.

Sound clip: Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand, Leon Fleisher with Lorin Maazel and The Cleveland Orchestra, March 22, 1975. (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/122927260?secret_token=s-YISU7″ params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

He returned to play the Ravel seven times and the Prokofiev once with the Orchestra before a performance at Blossom in August of 1988. On that occasion, Plain Dealer critic Wilma Salisbury wrote, “the pianist performed the dramatic work with complete authority…All expressive elements from jazz inflections to romantic outbursts were plumbed to the depths of musical meaning. The final cadenza roared with triumph over the limitations of five fingers. The performance, as a whole, was breathtaking.”

In April of 1995, Fleisher made his triumphant return to Severance Hall as a two-handed pianist in Mozart’s twelfth concerto under Christoph von Dohnányi. Plain Dealer critic Donald Rosenberg wrote, “The pianist again was a model of incisive rhythm, exquisite phrasing and stylistic grace, as listeners will remember from the days he collaborated here with George Szell…It is a joy to hear Fleisher in any repertory. Here it was a privilege.”

Sound clip: Mozart Concerto No. 12, Leon Fleisher with Christoph von Dohnányi and The Cleveland Orchestra, April 20, 1995. (Cleveland Orchestra Archives)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/122928341?secret_token=s-L7an1″ params=”color=ff6600&auto_play=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Fleisher’s return was so newsworthy that the Baltimore Sun sent a critic to cover the event, who noted that “For most classical music lovers, Fleischer’s return to two-handed playing is on a par with Bo Jackson returning as a star in both baseball and football.”

In fact, Fleisher now excels in three musical sports, the second of which is his conducting career. Did he pick up any tips from George Szell? “I would certainly hope so. But I’ve been around conductors all of my musical life, starting with Pierre Monteux of the San Francisco Symphony, who was the epitome of a certain kind of conductor. I don’t consider or call myself a conductor, I’m a musician who leads, who has musical ideas and I hope I can communicate them. But I make no pretenses of being the star conductor. I make music.”

Fleisher’s third career is that of a teacher, in which capacity he mentored Jonathan Biss, with whom he’ll be collaborating this weekend. In that regard, Fleisher’s impressive musical bloodline goes back through his teacher, Artur Schnabel, who studied with Theodor Leschetizky, who studied with Carl Czerny, who studied with Beethoven.

Biss thinks that Fleisher is truly deserving of the title Legend in His Own Time. “I remember the very first time I played with the Orchestra was with Beethoven’s fourth concerto. He wasn’t conducting and he wasn’t there but even that already seemed like some sort of karmic full circle moment for me. I remember practicing in the Szell library and seeing those photos of the recording sessions with the two of them together. He really has earned his legend. Not through any razzle dazzle or publicity but just because he is so inarguably great.”

Biss is now passing the Fleisher tradition along to his own students at the Curtis Institute. Those include piano students he encounters face to face as well as the astonishing 30,000 students who have enrolled in the Coursera course on Beethoven’s piano sonatas. “I was shocked!” he said. “The staggering number of people who have signed up for the course just reflects the fact that there is this huge audience for classical music.”

For Jonathan Biss, who is eagerly looking forward to this weekend’s performances, filling in on short notice for other performers has become second nature. “I’ve gotten that phone call a number of times and this is at least the sixth if not the tenth time I’ve done a replacement in my life.”

He’s delighted that this assignment is two Beethoven concertos. “What is it about Beethoven? He was someone with such forcefulness of personality married to such unbelievable ability that he was able to write music which not only makes an enormous impact but goes unbelievably deep. There are very few artists in any medium who have done that and Beethoven is among them.”

Thanks to Cleveland Orchestra archivist Deborah Hefling for her invaluable help with research for this article.

Daniel Hathaway contributed to this article.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 3, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.