by Mike Telin

The origins of the Chorus can be traced back to the Orchestra’s third season when, in October of 1920, founding Manager Adella Prentiss Hughes issued the following invitation: “A Chorus is now being organized, to be known as The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus. As the name implies, this new organization is designed primarily as an adjunct to the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, for the purpose of enlarging its activities and enriching its repertoire.”

The invitation went on to note that works such as Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, Liszt’s Faust Symphony, and Mahler’s 8th Symphony all call for a chorus, and continued, “The opportunity to join this chorus is now open to all who are interested in choral singing and who wish to be identified with the performance of great masterpieces in conjunction with our splendid Symphony Orchestra. Rehearsals will be held at regular intervals in the Ballroom of the Hotel Winton.” The Chorus, led by then Orchestra Assistant Conductor Arthur Shepherd, lasted less then one year.

Attempts were made during the mid 1930’s to form choral ensembles. Ad hoc groups were formed for special events such as the February,1931 opening of Severance Hall. For a decade, there was the Cleveland Philharmonic Chorus, which performed works such as the Verdi Requiem in 1937 and Bach’s St. Matthew Passion in 1938. And a smaller group, The Cleveland Orchestra Opera Chorus, was formed in order to provide a chorus for the staged operas that were produced and directed by the Orchestra’s second music director, Artur Rodzinski.

In 1952, George Szell, who was “unhappy with the quality of ephemeral choruses,” called for the formation of a permanent ensemble. Writing for the Cleveland Press in February of 1952, Arthur Loesser noted, “There has been no permanent chorus associated with the orchestra since World War II, but the tremendous success of the Ninth Symphony last spring, as well as eager response to the announcement of its forth-coming repetition, has encouraged Szell and others to aim to make presentations of great choral works a regular feature of the orchestra season.”

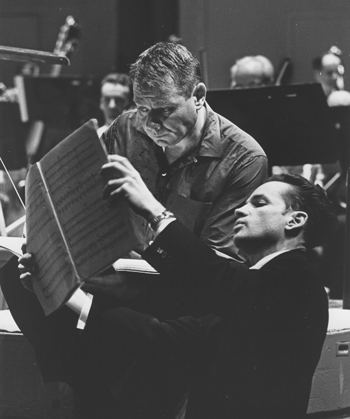

Shaw with Louis Lane

Then, in 1956 George Szell invited a young choral conductor by the name of Robert Shaw to join the orchestra’s conducting staff as chorus conductor and associate conductor.

A document prepared for the Chorus’s 50th anniversary in 2002-2003 stated, “The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus is one of the few professionally trained, all volunteer choruses sponsored by an American Orchestra.” The document also pointed out that the chorus has made 20 recordings with the Orchestra, four of which have won 5 Grammy Awards. They have performed repertoire by 66 different composers and the top five most often performed works with Orchestra includes Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus (119 concerts in addition to nineteen performances of the complete Messiah), Beethoven’s Symphony #9 (48 concerts) Mahler’s Symphony #2 (22 concerts), the Verdi Requiem (21 concerts) and Brahms’s A German Requiem (nineteen concerts).

Most impressively, the 170 members donated over 40,000 hours annually in rehearsal and performance time and have raised over 1.3 million for past and future touring.

Although every member deserves to be featured, due to space restrictions, we have asked two very insightful and dynamic members to share their thoughts on being a member of that select group known as The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus.

Emily Austin

Emily Austin told us that this fall will mark 20 years as a chorus member. “I’ve loved every minute of it. It’s the love of my life, it really is.” Austin, who has performed the Mozart Requiem with the Orchestra at least five times, said that while she never sang it in college, “the first time I sang it in Cleveland I thought I had died and gone to heaven.”

Austin said that the opportunity to tour is something special. “It just does something for us musically through a non-musical means. We sit next to people on the bus, and wait for things with people we don’t sit next to in our section and we get to know them. I don’t know what the psychology of it is exactly, but we make better music when we’ve traveled together. It’s something non-musical that connects us in a deeper way.”

Austin recalls that her first tour with the Chorus was to England and Wales. “This was on our own without the orchestra. We sang both Belshazzar’s Feast and the Brahms Requiem. We’ve also been to Edinburgh and Lucerne. This past November we were on a European tour singing Beethoven’s Mass in C. That was really fun because it had been a while since we had been on a European tour. And next March we’re going to Miami for performances of Carmina Burana and that is so much fun. It really is.”

There is not a time that Austin has not loved to sing. “I remember when I was five, my school music teacher and my parents were best friends and we went to their house for a Christmas gathering. I started singing Silent Night and my teach said, ‘Emily that was really nice but could you do it a little quieter’. My family loved music, bluegrass and classical. No one was trained in music but they always listened to the opera on the radio.”

Emily Austin studied music in college, majoring in voice at Murray State, and eventually earned a degree in Music Education from St. Joseph College in Indiana.

After teaching music at Lorain Catholic High School for nine years followed by a stint in the continuing education department of Ernst and Young, Austin found her way to the Music Settlement working in the office of the Performing Arts Department.

Being a member of the chorus also introduced her to someone who has become quite an important part of her life, her husband and long time Cleveland Orchestra second bassoonist Phil Austin. “Nancy Gage and I were sitting onstage at Severance Hall,” Emily Austin recalls. “I had never really seen Phil’s face, only the back of his head. Nancy told me that she wanted to find a nice man for me and she pointed to the back of Phil’s head. She told me about him and that he was or about to be divorced but said she would check it out.” After a period of time the two finally met. “I met him six weeks after his divorce was final. We started talking and we ‘shared the floor’. [Laughing] It was an equal conversation then and it has been every since.”

When it comes to conductors Austin said, “Pierre Boulez can make magic with his fingertips. He’s one of the few conductors who doesn’t use a baton. He just flicks a finger or looks your way or raises an eyebrow. It’s like being transported.”

Although there have been many great performances, one in particular stands out for her. The first year Austin was in the chorus they travelled to New York’s Carnegie Hall for a performance of Mahler Symphony #8 (Symphony of a Thousand) for the re-opening of the Hall. Robert Shaw was conducting and in addition to the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus the performance included the Atlanta Symphony Chorus and Choruses from St. Louis, Cincinnati and Oberlin.

“Singers were put in all of the box seats as well as the stage. I was on the stage next to people who weren’t from Cleveland. It’s really fun to meet people from other places. It was one of the peak musical moments for me. We all had ID tags to get into Carnegie Hall and me being from a little coal mining and farming town in western Kentucky, I though I had died and gone to heaven. And I knew that my high school band and choir directors would be so happy to know that I was getting to do this.”

The chance to sing under Robert Shaw made the experience even better for Austin. “I wrote down oodles of Shawisms in my music and he always used non-musical descriptions to get the effect he wanted. In one part we were not singing sad enough for him and he said, ‘the kind of sad this is, is that somebody could do something like they did in Oklahoma City.’ This was right after the Oklahoma City bombing. We did it again and it was magic. At the end of the rehearsal he told us that he felt like the luckiest man in the world by getting to conduct this music. And when we do this music you get a special peek into God’s heart no matter what you perceive God to be.” Following the first performance Austin remembers the thirteen curtain calls quite vividly. “We were all crying our eyes out.”

Emily Austin tells me that if I had a week she could tell me even more. “Everybody I know who is or was in the Chorus has loved it. Our pay is not monetary and the reward that we get is something intangible.”

Ann Marie Hardulak

Ann Marie Hardulak has been a member for 42 years, joining under Robert Page.

Obviously she must enjoy it? “You know, I have always said that if ever I take this wonderful opportunity for granted I will leave and let someone else have the chair,” she responded, laughing. “It really is a joy to be able to sing with The Cleveland Orchestra.”

After 42 years does she have any stories to share? Again answering with a laugh, “Something you can print? But to be honest we all say the same thing when called upon: the best story for me is the family that the chorus has within its membership. We come from all different walks of life. There are members who are not musicians — like doctors, lawyers and people who build houses. Everyone does something different but we have this incredible bond as singers. I used to say, we marry them and we bury them, we sing at each other’s weddings and at each other’s funerals and I believe that that in itself is a story after all these years.”

Hardulak said that for her it’s not only the experience of singing in Cleveland, but also the opportunity to travel with the orchestra on tour. “All the different countries that we have been able to sing in over the years has been such an experience. And to be able to sing with the different conductors as well is another experience. These are things that the average person just doesn’t get to do.”

For 24 years Hardulak was involved in Chorus relations as well. “I was on the Chorus operating committee. The committee makes sure that the singers have the time to sing and not to have to worry about anything else. As part of her committee work Hardulak mentored new chorus members. “I always would tell them, don’t be afraid to take a nap. Say it’s Christmas time and you’re doing two concerts in one day, that’s very draining. And sometimes you have two or three hours in between performances and you can’t go home because of distance, so I’d tell them, just curl up and take a nap in the chamber hall. It’s the best thing for you, assuming someone wakes you up in time for the next show. But the most important thing is to try take care of yourself because people have to stay healthy.”

All of the members of the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus donate their time. “[The model] is unique and fortunately everyone who sings wants to give the best that they’ve got. It’s not just a question of showing up,” remarked Hardulak. “I remember that Robert Page used to say, ‘If you know the notes you’ve only touched the hem of the garment.’ I think that philosophy has carried on over the years. It’s just an unwritten understanding that that is what we will do, whether it’s a three-hour rehearsal or like next week when it will be seven nights in a row. And as you know most people have worked all day then come in and do this, which always amazes the orchestra.”

With as much repertoire as Ann Marie Hardulak has performed there is still one piece that has yet to be programmed. “I’m still waiting for Bernstein’s Mass. I think it’s a piece Cleveland would like to hear. We certainly have had quite a few Carminas. It does tend to make the people happy and it’s always fun to perform. And people who don’t normally go to the orchestra will go to that, there’s just something about it. I don’t think Carl Orff had an inkling of how the piece was going to capture the world for so many generations.”

Are there any conductors or soloists who have stood out? “To be honest, I’ve been in so long that I’ve seen people come in as babies, in their late 20s, to conduct the Cleveland Orchestra and now I look at them when they come back and I think, my goodness what happened, oh yes, we’re all getting older,” Hardulak says with a laugh. “Like the wonderful James Conlon. He and I got into an interesting discussion a couple of years ago when the Chorus was a guest at the May Festival.”

“Bob Porco had arranged for both of his choruses to sing together at the festival. I bumped into Mr. Conlon outside and he recognized me from being from Cleveland and I mentioned one of the first concerts he conducted in Cleveland when he was quite young. And he said, how would you know this? And I said, because I was there. He said you must have been a child. And I said, no, I was in the chorus. I guess it’s a long way of saying that I remember some of these tremendous conductors coming in as young people and it’s fun to see how they change over the years. The same is true with some of the soloists. But who stands out, that’s hard because there are just so many.”

Is there any one concert that she especially remembers? “There’re a lot of concerts that stand out — but for different reasons. There was a Berlioz Requiem in the 1970’s that we sang at Carnegie Hall that still stands out in my mind. We were so jazzed up from the performance that we could have flown home without a plane. This kind of thing has happened a lot over different decades and that is what always encourages me.”

Special thanks to Orchestra archivist Deborah Hefling and to Chorus member Beth Bailey for their assistance with this article.

Photo credits:

Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus by Roger Mastroianni.

Robert Shaw and Louis Lane: unknown.

Tour photo by Roger Mastroianni, 2000.

Singer framed by harp by Frank Muth.

On the tarmac: unknown.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 29, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article.