by Lilyanna D’Amato

Deeply problematic, the nickname casts this virtuosic musician as the lesser equivalent of a White counterpart. In his article, Joseph Boulogne, the Chevalier de Saint-George and the Problem With Black Mozart, Julian Ledford suggests that through this biased comparison, Saint-Georges becomes “a mythicized inferior of the status quo’s perfect symbol of 18th-century classical music.”

Historically, this is how the Western canon has always understood Black classical music: in contrast to a supposedly superior model. By severing Saint-Georges’ name from Mozart’s, we restore the legacy he is owed — a reckoning long overdue.

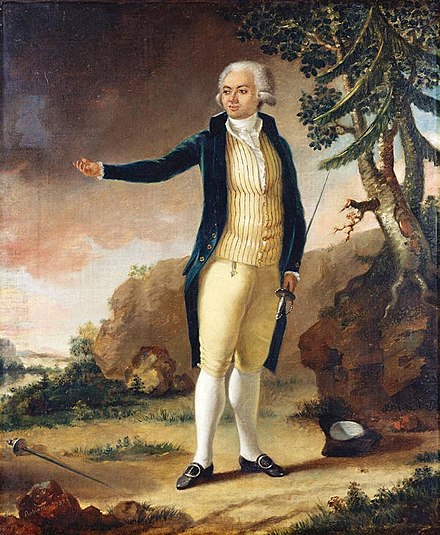

Born in the French West Indies colony of Guadeloupe, Joseph Boulogne spent his childhood on a plantation near Basse-Terre. The illegitimate son of a wealthy French plantation owner (a Gentleman of the King’s Chamber) and his wife’s 16-year-old Senegalese slave, the young prodigy received both music and fencing lessons from his father, ultimately travelling with him to Bordeaux for schooling in 1753.

After completing six years at the elite fencing academy of Nicolas Texier de La Böessière, where he famously bested fencing master Alexandre Picard and earned the epithet “god of arms,” Boulogne was made a Gendarme du roi, an officer of the King’s bodyguard, and given the title Chevalier. He was known henceforth as Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

While Parisian high society knew Chevalier de Saint-Georges as a world-renowned fencer, they were shocked to hear of his gift for music. In 1764, his brilliant mastery of the harpsichord and violin began to catch the attention of major composers, including Antonio Lolli, François-Joseph Gossec, and Jean-Marie Leclair. Within the year, he became concertmaster of Le Concert des Amateurs, composing what are believed to be the earliest string quartets, sinfonia concertantes, and quatuor concertantes. According to Le Mercure, his first two violin concertos, performed in the salons of the capital in the early 1770s, “received the greatest applause as much for the quality of playing as for that of the composition.”

As you can hear in this recording of his Violin Concerto No. 9 by Takako Nishizaki and the Cologne Chamber Orchestra, the work gleams with elegant urgency, shifting from movement to movement with delightful fervor. The twangy timbre of the harpsichord and the soaring harmonies of the violin create a thrillingly propulsive rhythm under an effortless velvety tone. The Chevalier paints a wondrous, energetic, and spritely soundscape: it’s as if hundreds of bows were dancing above the beautifully manicured gardens of 18th-century French nobility.

What’s more impressive is that Chevalier de Saint-Georges existed within this highly racist and exclusionary society at all.

Although his father’s noble status should have extended to the young prodigy, France’s Code Noir rendered Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges ineligible for titles of nobility. Originally established in 1785 by King Louis XIV, the royal decree outlined the legality of slavery in the French colonies, blatantly declaring the genetic inferiority of African-descended peoples. A century later, the law was amended to account for the increasing presence of free people of color in France, but beginning in 1762, the revised Code Noir required “Nègres et gens de couleur” to register with the clerk of the Admiralty within two months of arrival.

In his biography of the prolific composer, French author Pierre Bardin describes Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges’ endeavor, along with other people of color, to overcome these restrictive racist codes in effort to join the middle and upper classes. “It is undeniable that he was gifted” Bardin writes, “but his inborn talents were magnified by relentless effort, permitting him not only to be better, but above all to overcome the racial barrier which put him in the disdained social class of “Mûlatres” (“Mulattos”) because his father was White and his mother was Black.”

In many ways, he succeeded. In 1776, he performed for Queen Marie Antoinette at Versailles, publishing two sinfonia concertantes in the same year and two more in 1778. Although his royally-endorsed bid to manage the Paris Opera was rejected because three female musicians felt “their honor and their delicate conscience could never allow them to submit to the orders of a mulatto,” he went on to direct the prestigious Concert de la Loge Olympique, premiering Haydn’s six “Paris” Symphonies, Nos. 82-87, in a triumphant series of concerts in 1787.

At the onset of the French Revolution in July 1789, Chevalier de Saint-Georges was living in Lille. “For a lot of his life, he was friends with the aristocracy. And so he owed a lot of his prosperity to the monarchy,” journalist Andrea Valentino said in his Atlas Obscura article, The ‘Black Mozart’ Was So Much More. “And yet, when it came down to it, he decided to side with the Revolution.”

During the War, he bravely led a thousand black infantry and cavalry men, heroically leading what came to be known as the “Légion Saint-Georges.” Unfortunately, though, as the French Revolution descended into chaos, Saint-Georges was accused of treason and wrongly imprisoned for eleven months. When he was finally released in the late 1790s, the Chevalier had suffered a series of infections and stomach ailments. On June 12, 1799 — poor, alone, and just 53 years old — he died of gangrene.

While much of the Chevalier’s music was lost during the Revolution, and what survived was quickly forgotten, his music is now returning to the classical music Empyrean. As we marvel at his virtuosity, some of us for the first time, let us remember this legendary musician for his personal talents, triumphs, and trials — mindful to forgo any ancillary allusion to a certain Austrian composer.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 14, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article