by Rory O’Donoghue

“The whole mechanism of getting pieces played isn’t always factored into the commissioning of a piece,” the world-renowned harpist said by phone from New York. “You’ve got to premiere music, and then launch it. It’s like the last scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark, where after risking everything, the precious artifact gets hoisted up on a forklift and chucked onto the top shelf of the National Archives to gather dust — that’s sadly what happens to so many pieces of music. There’s a big difference between having the music, and having the music stay alive.”

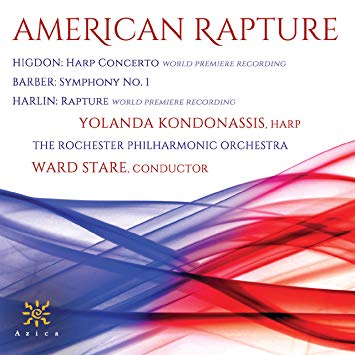

If the survival of new concertos is at risk, then Kondonassis is their EMT. Recent commissions include works by Bright Sheng, Keith Fitch, and Gary Schocker, and she has a keen aptitude for not only incarnating contemporary music, but also ensuring its durability. I got the chance to talk to the busy musician (“It’s been a wild and woolly week for me — I’ve been on the move every day”) about American Rapture, the new album on the Azica label, which presents Kondonassis’ world premiere recording of Jennifer Higdon’s Harp Concerto with the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

Rory O’Donoghue: Congratulations on your new recording of the Higdon. How did this project come about?

Yolanda Kondonassis: It was a big, multifaceted project. Like most of these rather large endeavors, it started about ten years ago. I was just finishing up another harp concerto premiere commission (by Bright Sheng). I remember starting the conversation with Jennifer while I was doing the premiere series of the Sheng, which I set up similar to this one. Whenever you have a well-known, award-winning composer, it makes sense on a lot of levels to make sure the piece gets played. For both of these projects, I had five orchestras (this one, six) on board, and that guarantees that the piece isn’t just a one-off. It takes so much to write a large-scale work, and so much effort to nail down a composer. It’s terrible if it’s only played once, and that sadly happens for a lot of concertos out there. There are actually quite a few concertos for harp, and most of them don’t get played. With a project like this, I’ve always known that it’s not just about trying to make the commission happen — you’ve got to usher the piece into the world, and then make a recording. A recording is what ensures the piece a life after the premiere series, because orchestras are going to want to hear it to program it. Live concert tapes just don’t do justice to a piece with as much color and interest as Jennifer’s music.

RO: What was working with Jennifer Higdon like?

YK: Before she started writing the piece, I flew to Philly and we spent the day together. We had a lovely lunch, and we talked about everything. Then I got my hands on a harp, we sat in a room together, and I played for a few hours. We talked about what works particularly well, what doesn’t work well, and what I like to play. She was able to get a feel for it. Of course, she’s written for harp before, and she knows what she’s doing. It’s just good to really get a handle on the timbre, and the range of colors. It’s nice for composers to get a feel for the particular artist they’re writing for. It’s almost like a little signature. When you look at concertos written for certain artists, you get a sense of their personality. I love that she incorporates that idea into her work process.

RO: You’ve done numerous world premiere recordings — how do you approach recording a new work, compared to recording standard rep?

YK: About the same. I’m a research hound in anything I do, and I’ve been that way ever since the very first recording I made for Telarc. I think this is my 22nd or 23rd since I started making commercial recordings. And I do the same thing every time, of a fashion. I amass every recording I can find, and for premieres, I listen to everything I can by the composer — not to imitate, but to know what is out there. To know what the pitfalls are, and what the recording issues are. The harp is hard to record for — ridiculously hard. Telarc was such a wonderful collaborator for that, since they’re all about sound, and I’ve found the same process working well with Azica, who I record for now. They’re not just happy to get it down on tape. They strive to make it as dimensional as possible. In that way, recordings are an art form of their own, in terms of capturing the unique soniorities that might not even register to a listener sitting in the middle row halfway back in the concert hall.

RO: I have to admit, I didn’t even realize it was a live recording.

YK: Isn’t it amazing? I don’t know how they managed that. In my notes, I wrote ‘Thanks so much to the wonderful Rochester audience who stifled their coughs and silenced their cell phones.’ One of my favorite things to do in live performances is go for that incredibly precious silence, when you know everybody in that giant venue is in the same space with you. This is one of those pieces that has many of those moments, and it opens that way. I love the challenge of starting by myself, and wrapping us all into the same spell. But with a live setting, I had visions of arriving at one of those beautiful moments, and then hearing a QUEEN song echoing through the hall, shattering the whole thing. In situations like this, you just have to think that some planets aligned to make it come out just exactly how you wanted it to.

RO: “The Higdon is playful, pretty, and energetic — could you walk me through each of the movements, characterwise?”

YK: It has unbelievable variety and contrast from movement to movement. The first one is called “First Light,” and it starts out with an extended period for harp alone. Without dissolving into predictability, it really does capture the solitary feeling of watching a sunrise. It’s even a slight homage to Aaron Copland, in that very American feeling of vast expanse, because of the open 5ths. There’s something sacred and stark about it. As the layers of the orchestra enter, it’s like the layers of a sunrise. It starts out with one pallette, and as you become aware of the lightening sky, it becomes vivid and bright. You imagine the deep purples, and it’s very rich and luscious. It ends as it began, with that rather solitary statement with the harp. It’s very fun to play, with lots of very tricky, intricate rhythms — it’s almost fugal. It’s challenging to make the interlocking pieces fit. Even though it’s a lyrical movement, the rhythmic structure that Jennifer writes has to interlock absolutely correctly, like legos.

It dovetails very naturally into the second movement, “Joyride.” Jennifer said something very interesting — it’s hard to write joy, without it sounding trite, or like something we’ve heard before to represent joy. I really think she did that. It’s got this very electric exuberance — just a kick to play. When we got together in Philly, I told her that it’s always smart to write conversationally for the harp, where the harp speaks and the orchestra answers, or vice versa. This happens a lot in the Ginastera, where I get to catch a wave with the orchestra and ride it, and be heard peeking over the top. In Jennifer’s piece, it happens so beautifully in both the second and fourth movements. I get to lock into a groove with the orchestra and converse with the thicker orchestra texture. There’s a spot about two-thirds of the way through where I’m always beside myself looking forward to playing it, because it just works so well.

The third movement, “Lullaby,” was inspired by my relationship with my daughter. During our lunch I’m sure I waxed on ad nauseum about my daughter, and how much I love her and all, so Jennifer wrote this movement with that in mind, and it means the world to me. What I find uncanny is that it’s not a sleepy lullaby. She must have picked up on the fact that my daughter is a fairly precocious kid — she’s not much of a sleeper. It has great flow, even within the context of a lullaby, and it’s got that interest, that color, that multi-layered writing that keeps things from ever dissolving into predictability. I think that’s one of her main assets as a composer. She manages all this color, all this originality, but it never dissolves into anything like we’ve heard before. The ending of the lullaby again has one of those special moments I described, where we all wrap together in our listening. It’s this wonderful, settled chord, which is so much fun to plant. I love a chord that I can place in its perfect, inevitable spot. It’s working with timing and color as if you’re a sculptor. To be able to do that on a live recording is a wonderful privilege.

The last movement, Rap Knock, is utterly different from everything else. The harp is a percussionist for the entire first page. I’m not playing notes at all, just entering an intricate knocking dialogue with the percussion section. I really had to practice my percussion for that one. That movement is a rip-roaring’ good time. It’s fun to let loose in a virtuosic way at the end and really wail, which she lets me do.

RO: Thank you for that colorful description — it’s such a varied piece.

YK: It’s a wonderful collection of short stories that fit together even though they’re all completely different. I think that’s one reason why people seem to like the piece so much. That was probably the biggest goal of this project — to have a little hand in commissioning a piece of repertoire for the harp that will live on, get programmed, and stay popular.

RO: How do you view the Higdon in the context of solo harp literature?

YK: I often say that the repertoire for my instrument is behind. The first functioning double-action pedal harp didn’t come about until the early 1800s. But that said, we have reams of music — again, most of it just doesn’t get played. I think the Higdon will.

RO: You’ve got such a busy schedule, with teaching, performing, recording. What’s the life of a touring harpist like?

YK: No week is like the last, but I love the way things are set up. This last year was particularly insane from a travel and touring standpoint. I usually try to pace it out just a little bit, to avoid exhaustion. When you’re a harpist, you don’t just walk onto a plane, walk off, go play your concert, and leave. There are so many more logistics. This past year I played Ginastera several times, once in Poland, I did quite a few concerts with Jason Vieaux, and I did all these Higdon premiere performances. For each of these projects, there’s administrative time just setting up the logistics of the instrument. I have to make sure I’ll have a good harp to play, hopefully even one I’ve played before. Very often, if I can’t find a harp that I’m sure will work in the city I’m going to, I’ll fly to somewhere else nearby, rent a minivan, pick up a harp, and then drive to the actual concert destination. Luckily, I really do enjoy travel. That part of the touring life is a joy.

Just about every year I do a recording. I’ve been working on a book that will be out later this year, called The Composer’s Guide to Writing Well for the Harp. It’s not just about contemporary technique stuff, but it gets into the physics of how sound works on the harp, and how to write for it idiomatically. This book has been writing itself in my head for 20 years, so it’s nice to be finishing that up.

Those are just a few of the different pieces of my life. Of course, at the heart of it, there’s teaching at Oberlin and CIM. I absolutely love my students. Like everything in this world, teaching — student activities and competitions, the visions that students have — has become more intense. As a teacher, all I want for my students is to succeed, in whatever way they do best. That’s a project too, for every single one of them. These days there are a lot of options, but they all take a lot of preparation. It’s fun to take a unique personality with a unique skill-set, combine it with a unique instrument, and ask: so, what are we going to do with you? How do we hone whatever you, individually, do best. That’s the creative aspect of teaching. It’s not just here’s the syllabus, let’s plough through this repertoire, this is what you need to learn before you leave, and good luck to you. If teaching ever was that way, more formulaic and all, it definitely isn’t now.

~~~

After our conversation, I thanked Kondonassis for talking to me while on the go. She said she welcomed the chance to chat in an air-conditioned room. “It’s been an inferno in NYC the past few days,” she said. “You’re so in touch with the elements in the city — if it’s raining, you’re soaked all day, and if it’s hot, you’re always on fire.”

Beyond that, she’s also deeply in touch with Jennifer Higdon’s music, readily apparent in her phenomenal performance on American Rapture. The album explores the ‘American sound’ in all its forms, and also features Samuel Barber’s Symphony No. 1 and the world premiere recording of Patrick Harlin’s Rapture.

The album is widely available online.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 13, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article