by Mike Telin

“This undertaking is unique to other schools in that all the performers are students,” violin professor Sibbi Bernhardsson said during a conversation in his studio. “The students are so excited — we’re all excited about this project, and it’s been all hands-on-deck. The entire string faculty is involved coaching the groups. And some of the theory professors have been coaching as well by offering their perspectives. Some are highlighting the quartets in their courses. So there’s a great synergy around the project. Presenting the complete quartet cycle is exciting no matter where you are, but we’re doing it in five concerts over two and a half days.”

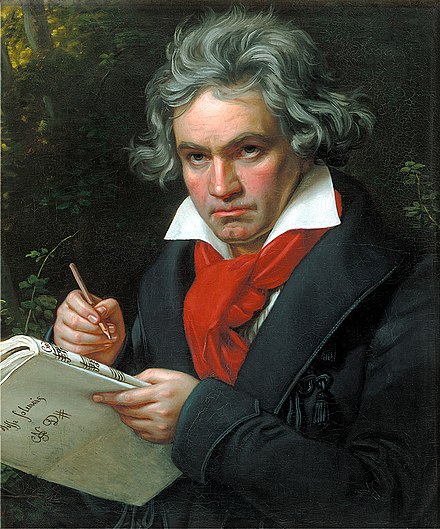

The violinist noted that works from each of Beethoven’s three periods — early, middle, and late — sound like music by three different composers. “Three great composers, but three nonetheless. And we are not presenting them in chronological order, so each period will be represented in every concert.”

The faculty began planning the project last year, and it has included a Beethoven Quartet intensive last fall as well as a special winter term project. “We wanted to involve as many of the students as possible, but there are also the realities of being in a conservatory — seniors are taking grad school auditions, opera and orchestra rehearsals, etc. So we are splitting the sixteen quartets and the Große Fuge between twenty groups. The majority are playing an entire quartet, although three of them will be split between two groups.”

Having spent seventeen years as a member of the award-winning Pacifica Quartet, Bernhardsson understands the value of having all students study the quartets, not just string players. “It’s important to know that when Beethoven was writing the Opus 18s he had just come to Vienna to study with Mozart, but Mozart died and he ended up studying with Haydn. So the Opus 18s are deeply rooted in the early classical tradition. They are clearly in sonata form and the length is similar to Haydn and Mozart. And the phrase structure is also deeply rooted in what makes pieces ‘classical.’”

Then came the composer’s famous Heiligenstadt Testament to his brothers Carl and Johann, where he said that there was so much music left to be explored and that would be a source of inspiration to continue living. “That’s what we call the ‘heroic period.’ He wrote symphonies three through eight, the Violin Concerto, the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Piano Concertos, and a lot of the famous piano sonatas.”

During this period the composer’s approach to writing string quartets also evolved. “The dynamic range became greater and while they were still basically in sonata form, he might have two developmental sections. And what he requires instrumentally of each player also expanded. For lack of a better word, the pieces are more romantic in sound and the lines tend to be longer.”

Then the composer experienced a compositional draught. He also lost respect for himself. “He was not bathing and not paying his bills. He was more isolated and developed health problems. And again, he fell into a great depression and contemplated suicide.”

Then, Bernhardsson noted that two things happened: he had a spiritual awakening and began studying the music of Palestrina and Bach. “Beethoven was a connoisseur so he knew Bach, but nobody else knew Bach. And that became a source of inspiration for his late period. He started implementing counterpoint, writing fugues, and using structures from the Baroque and Renaissance period. We are also dealing with a person who had come to complete terms with his fate as a musician and human being. He’s not even concerned about his contemporaries, he’s writing for the future.”

Bernhardsson hopes that audiences will enjoy immersing themselves in Beethoven’s sound world and come to understand that although the composer was a complicated person, his music is filled with optimism. “Some of these quartets I’ve rehearsed for thousands of hours and performed so many times, but they are still so interesting and fresh. When I’m coaching them, it’s like Beethoven is still speaking to us 250 years later — surprising us in such a profound way.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 3, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article