by Kevin McLaughlin

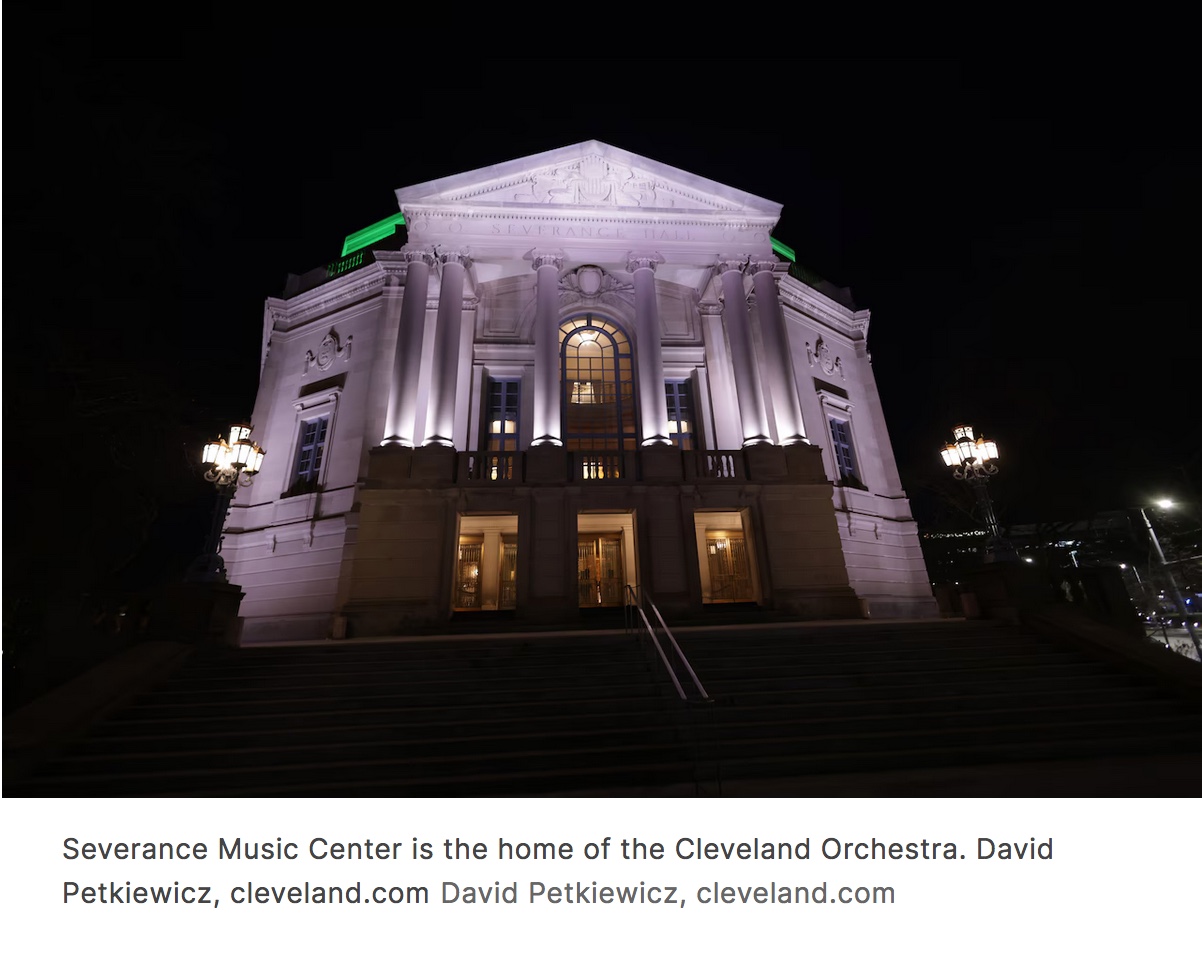

CLEVELAND, Ohio — The Canadian Brass brought its customary brilliance and easy rapport to Severance Music Center on Monday night, in their holiday program “Make Spirits Bright.”

There was plenty of fun to be had for sure, but unlike the frivolity of Canadian Brass concerts of the 1970s and ‘80s, this was a more disciplined product.

Playing their trademark tune, “Just a Closer Walk,” they marched in New Orleans-style from the back of the hall, dressed in black suits and white Nikes. Then a Christmas carol quickly followed. But that light music — maybe the lightest on the program — was soon unmasked as being not an opening number, but an encore. “You can never take those for granted,” explained tubist Chuck Daellenbach, the group’s only remaining original member.

Could it be a sign of the total acceptance of a brass quintet that a performance of The Magic Flute Overture, the actual top of the show, should be accepted as conventional, and not, as it once might have been, as a novelty? In any case, Mozart’s music glided and exulted, just as it would from any orchestra.

In J.S. Bach’s Italian Concerto, the Canadians achieved a seamless blend, purring out rounded legato lines, as if regular breathing were unnecessary. The arrangement, by trumpeter Joe Burgstaller, succeeded as both technically plausible and musically satisfying.

In addition to wielding influence as an arranger, Burgstaller took center stage several times as soloist, notably in two Piazzolla works on the second half. His beautiful, soaring lines in Oblivion — some improvised — would be the envy of any singer or instrumentalist. He made extremes (low, high, fast, smooth) seem easy, and having put aside technical concerns, gave in to pure loveliness.

A holiday highlight was the impressionistic “Christmas Time Is Here,” by the jazz pianist Vince Guaraldi from his 1965 classic score, A Charlie Brown Christmas. Playing flugelhorns, trumpeters Burgstaller and Mikio Sasaki quoted “Linus and Lucy” with lightning fluency, like a couple of unfazed beboppers. “O Tannenbaum” followed, featuring lampooning of wa-wa mutes by trombonist Keith Dyrda. In “What Child Is This,” hornist Jeff Nelsen joined his colleagues in an impressive display of chamber music synchronicity.

A welcome feature of this band’s bag of tricks was its members’ ease at the microphone. Comments were well-targeted and clarifying without going off track. Every player had an opportunity to talk, and all managed to endear themselves while demystifying the performer’s art.

The final selection, which came much too soon, may have appeared untethered to the logic of the program. Announcing Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, Daellenbach rationalized that the telling of the Arabian Nights story continued over three Christmases, thus making it a good fit. Impressive arranging and execution aside, this abbreviated version may have delivered less than promised.

For the real encores, the Canadians had two arrangements by the late Luther Henderson ready to go. “Frosty the Snowman,” a theatrical conceit, required Daellenbach to “melt” onto the stage floor, as the music grew “hotter.” “Saints Hallelujah,” something of a Brass signature piece, crosses “When the Saints Go Marching In” with the “Hallelujah” chorus from Handel’s Messiah. Here the Canadian Brass proved that whether highbrow or low, they’re still a tight little band.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 30, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article