by Tom Wachunas

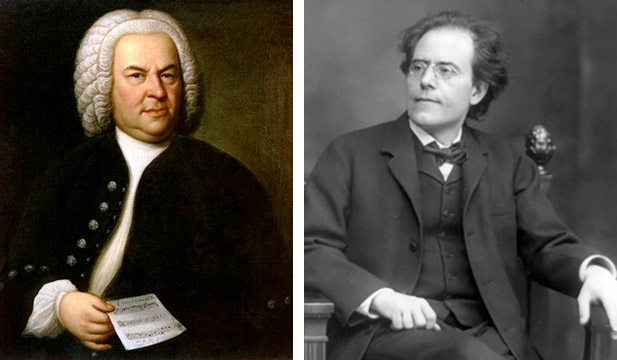

On this occasion, beginning with Bach’s much beloved Double Violin Concerto, what was old seemed new again. The impeccable virtuosity of the featured soloists — Vivek Jayaraman, who served as CSO concertmaster for the 2016-2017 season, and current CSO principal second violinist, Solomon Liang — imbued the work with intense expressivity.

Here was a partnership of two distinct musical presences engaged in an extended conversation built on intricate contrapuntal themes. Jayaraman’s demeanor seemed for the most part stately and authoritative in a gentle sort of way. Liang’s stance was no less authoritative, and he was also especially animated in his youthful panache, looking at times like he was about to break into a dance.

Together, they brought a palpably joyous energy to the music, which fluctuates between passages of pastoral calm and aggressive solemnity. The blending of these individual voices was particularly remarkable during the achingly poignant Largo movement, as if the two had magically become one tender voice. Throughout, the crisp precision and warm tonality of their playing was beautifully balanced with the steady flow of harmonies and rhythmic coloring from the string ensemble.

Hearing Mahler’s Symphony No. 5 is to embark on an arduous existential trek, a daunting trudge through both the darkest and brightest realms of being alive. Making the journey is ultimately a rewarding endeavor, like climbing a mountain. I can’t begin to imagine what it feels like to perform it. I can report only that music director Gerhardt Zimmermann and his 87 accomplished climbers, so to speak, rose to this complex, episodic occasion with astonishing resolve and thunderous sonority. They successfully brought the audience through to its feet, standing in adulation of a sensationally triumphant musical summit.

Long before getting there, we first heard a doleful trumpet lead us on a lumbering, funereal march. It was an inconsolable outcry of grief ending with a grim, muted thump from the low strings, only to give way to more savage turbulence in the second movement. The orchestra was a startling maelstrom — or ravaged landscape — of conflicting psychological and emotional states, interrupted by an all too brief moment of soaring nobility from the brass. A very long silence ensued before the vigorous, lilting third movement. The wondrous clarity of the horns here evoked a spirit of innocence, nostalgia, and hope.

And then there was the famous Adagietto movement, long regarded as Mahler’s encoded love letter to his wife, Alma. Here was an inspiring, contemplative portal to serenity, delicately carved out by the strings, like a quiet, sunlit stream, shimmering with gentle strums from the harp.

The radiant, soul-stirring optimism of the Rondo-Finale concluded not with a protracted chordal crescendo, but rather with accumulating rushes of abundantly textured phrases ascending to a single crackling note, like a lightning strike. It was a bold-faced final period in an epic essay. This was not really an ending so much as an ebullient arrival.

Mahler said once, “When I have reached a summit, I leave it with great reluctance, unless it is to reach for another, higher one.” That statement resonates all the more when considering how consistently the CSO arrives at ever more formidable artistic peaks with enthralling power and grace.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 1, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article