by Neil McCalmont

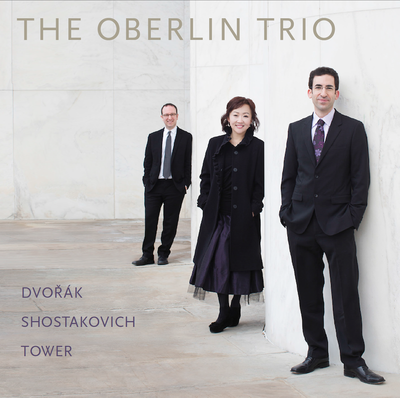

Their most recent CD, released this year on the Oberlin Music label, explores three highly personal piano trios by Dimitri Shostakovich, Joan Tower, and Antonín Dvořák. The variety of styles, ranging from Dvořák’s expressive romanticism to Tower’s intense modernism and Shostakovich’s eclectic polystylism, creates a welcome balance. The album is available on Amazon, iTunes, and in stores — and the disc comes with snazzy packaging, as well.

Shostakovich’s Piano Trio No. 2 in e, Op. 67 is one of his most enduringly popular works, composed in 1944 in memory of one of the composer’s dearest friends, polymath Ivan Sollertinsky, who died unexpectedly of a heart attack that same year. Shostakovich had also just lived through the apocalyptic siege of Leningrad, and his anxiety about death can be felt through the entire work.

The trio opens with a solo cello line that would sound high even on a violin. Eldan achieves a remarkable balance between soft, delicate beauty and longing pain, which continues as the other instruments join in the lament. The second movement jaunts around like a dance of death, with relentlessly jabbing notes. You might even hear the vicious shrieking of ghouls in Shostakovich’s writing, which Bowlin captures without losing his brilliant clarity of sound or remarkable intonation. Song’s dramatic phrasing and scrupulous attention to dynamics drive the entire third movement, a set of heart-wrenching variations over the piano’s bass line. The piece culminates in a dance finale, which includes Shostakovich’s first use of Jewish klezmer music, drawing on the influences of the Holocaust around him. The barely audible ending hovers high in each instrument’s register, as if the music itself moves on to the next realm.

Composed in 2000, Tower’s seven-minute Big Sky was inspired by the mountainous skyline the composer saw while riding horses during her childhood in Bolivia. The compact work travels through many moods that provoke mystical, introspective, and sometimes terrifying feelings — the transitions are crafted particularly well. No matter where this musical journey takes the Oberlin Trio, they play as though one voice were telling the story in raw emotions.

Dvořák’s Piano Trio No. 4 in e, Op. 90 is a landmark in the history of the genre. Written in 1891, it breaks with the traditional four-movement layout, and leaves behind standard Classical forms as well. Its subtitle, “Dumky,” originally referred to a melancholic, epic ballad, but many Slavic composers have used the term to describe a slow, lamenting piece interspersed with brisker dancing moments, which is how all six movements play out.

Bowlin, Eldan, and Song capture an exquisite balance in their interpretation, playing with a lush, expressive tone but never losing their crystal-clear sound. An undertone of nostalgia — an absolute must for Dvořák — pervades their whole performance. Most impressive is the Oberlin Trio’s emotional directness and how well they play off of one another. They have a strong mutual understanding of how the music flows and how it ought to be shaped, whether in the distraught and reflective “Dumky” passages or in the naïvely joyous dances.

The collaborative efforts of the Trio result in an admirable and enjoyable listening experience, making this album a great choice for the casual listener as well as for the connoisseur.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 14, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article