by Daniel Hautzinger

Both pieces, along with three suites, were written for the legendary cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. Britten and Rostropovich were friends and collaborators, and recordings exist of Britten conducting the Symphony with Rostropovich as soloist, and of the two performing the Sonata (Britten was a fine pianist as well as a composer).

Rostropovich and Britten cast both works as epic dramas, life and death conflicts. Bailey works on a smaller scale: in the Symphony, he becomes a dire prophet warning of the apocalypse.

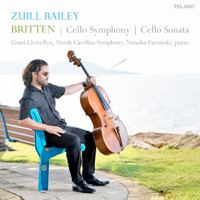

Titled “symphony” instead of “concerto,” it positions the cellist more as a narrator than a soloist, while the orchestra becomes both the setting and the characters. Incredible virtuosity is in the service of emotion rather than flash. The performance was recorded live with Grant Llewellyn leading the North Carolina Symphony in a tight performance. Bailey still nails every difficulty, and the high stakes grant his playing an edgy passion.

The piece begins portentously, with desperate chords from the cello over low rumblings in the orchestra. Bailey sounds as if he is ripping his instrument to pieces with the violence of his bowing. Soon the cello wanders off into a bombed-out landscape and becomes a raving refugee, terrified and lost. Despite the erratic, mad lines, Bailey and the North Carolina Symphony play with purpose and vehemence.

After the agitated lunacy and babbling crowd of the second movement, the cello enters into a psychological battle. Over eerie, steady orchestral chords, the solo part jerks from uncertain lyricism to weeping cries, fighting to overcome the horror that has come before. Bailey’s excellent tone control burnishes lines that traverse the entire range of the cello. He endows the bowed lines and pizzicatos of the cadenza with separate personalities, crafting a dialogue that leads directly into the almost jaunty last movement. Despite brief recollections of the earlier strife, the terror is gone and the work ends in an affirming major key, man emerging mentally scarred but triumphant.

Bailey’s performance of the Cello Sonata with pianist Natasha Paremski is less earth-shaking. It lacks the acute emotionalism and wrenching outbursts of Rostropovich and Britten’s recording, as well as the intense passion Bailey brought to the Symphony. Perhaps the lack of an audience in Oberlin Conservatory’s Clonick Hall kept him from unleashing his full self.

It’s still an impressive performance. Bailey’s thorny passages sound just effortful enough. Paremski is attuned to the music, especially in moments like the exquisite turn to major in the first of the five movements. The performers don’t quite bare their souls, but this is music of outsized emotions and grotesque pain, human trials exploded to a cosmic level. You have to admire their courage in the face of such daunting material.

The excellent production is by the Grammy-winning Five/Four Productions team of Thomas C. Moore, producer, and Michael Bishop, engineer.

Zuill Bailey will perform and give a master class in Oberlin Conservatory’s Stull Recital Hall on January 29, as part of the String Quartet Intensive and Festival.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 20, 2014

Click here for a printable version of this article.