by Mike Telin

Although CAP’s list of recipients reads like a who’s who of the region’s most influential artists, a closer look reveals many names that are conspicuously absent. “People come up to me and say, ‘How come Langston Hughes never won the prize, how come Ernst Bloch never won?’” Cleveland author and biographer Dennis Dooley said during a telephone conversation. “I tell them, that’s because the Arts Prize didn’t exist yet.”

In honor of its 60th anniversary, The Cleveland Arts Prize, in partnership with The Cleveland History Center, will recognize the region’s artist luminaries of days gone by with its Past Masters Project.

The year-long celebration kicks off on Saturday, December 4 with “Honoring Our Past Masters: The Golden Age of Cleveland Art, 1900–1945” at the Hay-McKinney Mansion. Doors open at 1:00 pm for a 1:30 concert that will feature music by five Past Master composers performed by members of The Cleveland Orchestra and guest musicians (download the program here). Tickets for the concert are available online.

At 2:30 Case Western Reserve University art history professor Henry Adams will introduce an exhibition of long-unseen masterworks by Cleveland artists. Masks and proof of vaccination and/or a negative COVID-19 test within 48 hours will be required for all events.

Past Masters Project curator Dennis Dooley, himself a 1986 Arts Prize winner for literature, noted that the project’s roster includes 60 honorees. To be considered, artists either had to have been born or spent their formative years in Northeast Ohio, or done important work while living here.

“I started by putting together a big list of people in the five categories that are awarded by CAP,” Dooley said. “Then I took the list to people who are authorities in each category and asked them what they thought of it and if they could identify people who may be missing.” Dooley then put together a jury for each of the art forms. “We decided on choosing 60 honorees for the 60th — that’s twelve in each category. But as time went on, more people came to light, so hopefully they can be added in the upcoming years.”

Cleveland Orchestra violinist and 2012 CAP winner Isabel Trautwein, who curated Saturday’s concert, said that the program represents only a small number of the “fabulous composers” who are part of the Past Masters roster, because many didn’t write chamber music.

“As far as we can tell, it’s only been played once, and it’s never been recorded,” she said, adding that they’re playing off scans of the manuscript. “It’s beautiful and very well written. We were saying that if Wagner and Bruckner had a compositional child, it would be this. It’s very chromatic but also very lyrical.”

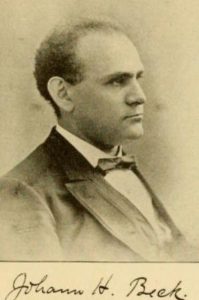

One peculiar aspect of the piece is that all of the musical instructions are written in German, not Italian, including directions such as crescendo. Trautwein noted that the composer also ran the Beck Orchestra in Cleveland. “I don’t know if they rehearsed in a language other than English, but it would be fun to find out. In any case it’s a look at history in a way that I wasn’t expecting to find.”

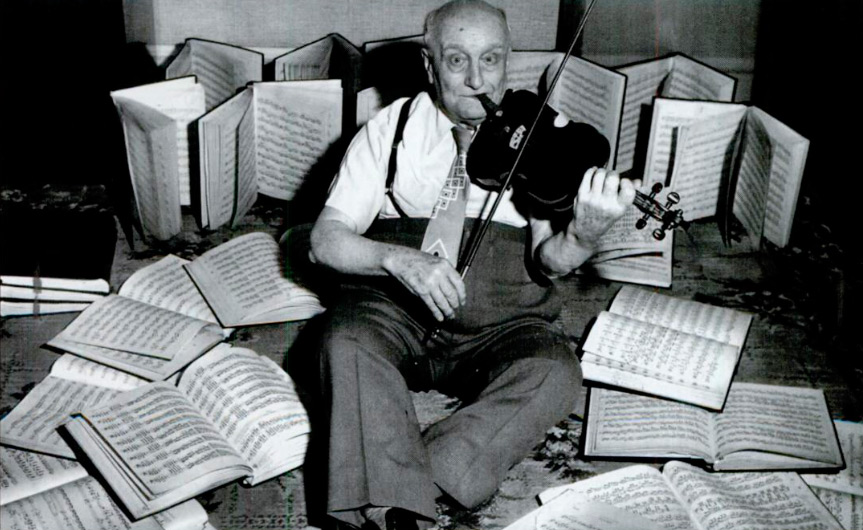

Another beautiful piece Trautwein pointed out is Charles Rychlik’s Duet for Violin and Viola. “What’s cool about him is that he taught thousands of children. The early Cleveland Orchestra had 40 of his students in it, so he was apparently a very good teacher and very loved. And you feel that in his music. The duet that we’re playing is dedicated to Dudley Blossom. Rychlik and Blossom were good friends, both violinists, and active at the Hermit Club, which must have been quite a creative hotspot back then.”

Rychlik also spent time in Prague where he studied with Dvořák. “Rychlik taught him English and was a boarder at Dvořák’s mom’s house. He even had dinner with Brahms and Dvořák. He used to tell the story of how the two composers talked about what kind of compensation they received. And Dvořák, who was much younger, was upset that people didn’t care for his serious compositions. Apparently Brahms jabbed him in the ribs and said, ‘Ha ha, do they ever really care about serious composition?’ It’s just fun to think about this. It brings the music to life and makes it less untouchable — to me, anyway.”

The program also includes music by Ernst Bloch, the first director of the Cleveland Institute of Music, and Douglas Moore, who in addition to composing his opera Ballad of Baby Doe, briefly served as the director of music at the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Trautwein said that the most unusual selection is a piece of silent film music by J.S. Zamecnik. “He was the Hollywood star of the group. It’s just fabulously written — very expressive. The audience was supposed to be able to hear the music and immediately imagine it matching the movie they were watching. When we rehearsed, everyone was just thrilled. It’s fun music.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 30, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article