by Peter Feher

One secret to last Tuesday’s polished program at Plymouth Church had to do with the group’s extracurricular nature. Thanks in part to seasons in ensembles including the Berlin, Los Angeles, and New York Philharmonics, the Quartet can pull off a big program easily, and with a certain unity of style.

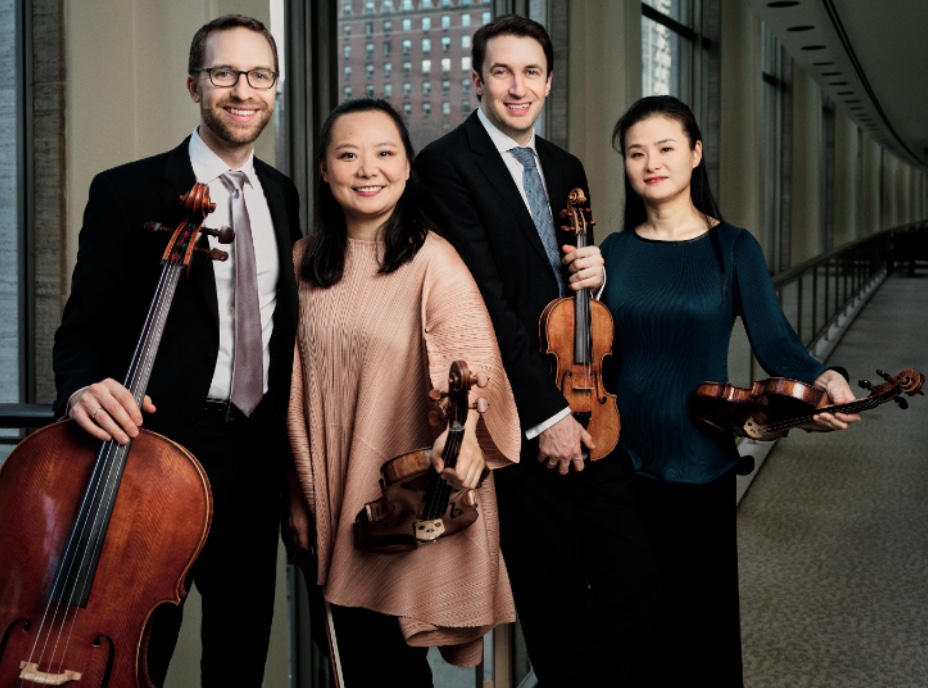

The ensemble has a uniformly rich sound from top to bottom, so much so that it can be hard to tease out who’s playing which part. Violinists Noah Bendix-Balgley and Shanshan Yao were often one unit, tossing phrases back and forth or perfectly in sync for a passage in thirds. (The pair are husband and wife.) Low-register notes went from violist Teng Li to cellist Nathan Vickery as if they were all on one big instrument.

At the same time, the Quartet was never too precious with any single detail or musical moment. The players preferred to think in bigger terms, hitting on concepts for particular movements while prioritizing the larger arc of the piece. For solo lines, they struck out on their own, confident that the rest of the group would keep a foundation they could ultimately return to.

The concert’s opener, Beethoven’s Op. 18, No. 3 Quartet proved just how sturdy the foursome are. As a result, they could take admirable risks like a truly pianissimo ending for the second movement (Andante con moto) and big, extroverted playing from Yao on the first violin part for the Presto finale.

The group’s penchant for the larger arc came through with Samuel Barber’s Quartet. As Bendix-Balgley explained from the stage, he and his colleagues conceived of the middle movement — better known in its orchestrated form, the Adagio for Strings — as the emotional core of a piece worth hearing in full.

Barber’s first movement starts with a unison gesture that then breaks away into sometimes calm, but more often agitated fragments. That music later returns as a truncated finale, with the Adagio as the transition. The Quartet gave the famous slow movement a full-throated reading, which made building the climactic crescendo a challenge, but paid off in the hushed measures that follow, and in the segue back to the Molto allegro.

The ensemble programmed its namesake piece, Schubert’s “Rosamunde” Quartet, to end the evening. This was an opportunity for Bendix-Balgley to shine, handling the melancholy melodies of the first violin part with the same sensitive care the composer intended for them.

It’s music you’d want to return to, and there’s no better inspiration for a chamber group that only gets together a few times a year.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 25, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article