by Mike Telin

At a very young age, Samuel Barber was already aware that he was destined to become a composer — a fact he made quite clear to his mother at the time. The Archives preserve an article from International Musician of December, 1961, where John Briggs writes

Early in this century an eight-year-old resident of West Chester, Pal, already with a number of compositions to his credit, left a note on his mother’s dressing table. It read in part:

“To begin with, I was not meant to be an athelet (sic) I was meant to be a composer, and will be, I’m sure…Don’t ask me to try to forget this…and go play foot-ball.—Please—Sometimes I’ve been worrying about this so much that it makes me mad! (not very).”

That destiny proved true. At the age of twenty-six, Barber came to Cleveland for the American premiere of his Symphony in One Movement (Symphony No. 1) at Severance Hall (January 21 and 23, 1937) under the direction of Artur Rodzinsky. (Barber’s piece shared the program with Respighi’s The Fountains of Rome, Dvorak’s Violin Concerto with local prodigy Erno Valasek and Walton’s Suite from “Façade.” A Halle Brothers ad across from the program advertised a new Steinway grand piano model for your home for $885).

The Barber premiere received national attention. On February 13, 1937 The Musical Courier wrote

Samuel Barber’s symphony in one movement was a distinct asset to our repertoire. It revealed the natural musical gifts of the young composer, who was present to witness a decidedly friendly reception of his work. With this score of a clearly defined melodic line, expertly written and splendidly orchestrated, Mr. Barber proved that one may be modern yet follow certain rules of form adhered to by the masters. The engaging work was given its first American performance by Dr. Rodzinski; having been previously performed in December by the Augusteo Orchestra in Rome under Bernardino Molinari.

Musical America had this to say on February 5, 1937 (published on February 10, 1937):

Enthusiastic audiences greeted the American premier of Samuel Barber’s Symphony in One Movement at the Cleveland Orchestra concerts of Jan. 21 and 23, conducted by Artur Rodzinski. The general concensus of opinion was that it is an outstanding work. … Its first American performance in Cleveland should open the way toward wider recognition of a young man who promises to be an important figure . Mr. Barber was present to that concerts and was called to the platform to receive the honors justly due him.

Barber builds the work on two simple themes in different metre, with two additional subsidiary themes. There is no slow section; a clever scherzo leads into the final portion of the work. Some extraordinary effects in scoring are heard, trumpets and trombones being contrasted in different rhythmical figures and woodwinds admirably used. A remarkable passacaglia, announced by the basses and developed powerfully by the strings, is a highlight of the symphony.

The local press was divided. Plain Dealer critic (and composer) Herbert Elwell began his review with an account of Erno Valasek’s performance and went on to talk about Barber:

The other youngster who did a lot of hand shaking on stage and took many a bow, was Samuel Barber, latest prize winner to return from the American Academy in Rome where he had a fellowship for two years and produced a “Symphony in One Movement” given its first performance in America last night, and a very good performance it was.

For me, this symphony emphasizes the current tendency of Americans to ‘write big’ regardless of whether they have anything to say. I do not imply that Barber is without ideas. He seems very voluble. But the dimensions of the composition are out of proportion to the real worth of its subject matter. It is inflated mid-Victorian oratory that has nothing whatever to do with the current American scene. The grandiose peroration, ecstatic and high-minded as it was, left me cold.

I am sorry I could not warm up to it, for this boy is richly endowed and has a tremendous technique for one of his age. He is only 26. Obviously, few in the audience felt as I did for the applause was extremely enthusiastic.

….What I really enjoyed at the concert was the glorious musical spoofing of the English composer William Walton.

Denoe Leedy of the Cleveland Press was effusive in his praise for Barber’s new work:

The Cleveland Orchestra concert of last night in Severance Hall was distinguished by the first American performance of Samuel Barber’s Symphony in One Movement, the latest work of the talented young composer who is now a Fellow in the American Academy in Rome…Now at the age of 26, he has cast off the shackles of his instructors and is creating music dictated by his own artistic conscience.

For so young a composer the symphony heard last night reveals an astonishing technical maturity. It is no simple matter to compress the traditional architectural features of the symphonic form into one movement. Even Liszt, when attempting to do something of the same order with the concerto tended to become diffuse.

Nevertheless the work stands as one of the finest examples of American music this reviewer has been privileged to hear. Its thematic ideas are always compelling; the orchestration, although in no way personal in color, is masterly; there is excellent rhythmic variety, and the psychological plan of the symphony remains intact, in spite of the compressing of the material.

The audience, well aware of the work’s significance, brought the composer back to the stage at least five or six times.

After its American premiere, Barber’s symphony was revised and performed in the new version by The Cleveland Orchestra under George Szell from February 3-5 in 1949, with repeat performances from March 31 through April 2 of that year. Yoel Levi conducted the symphony in 1992 (February 27-29) and it was last performed at Blossom under the direction of Steven Smith on July 15, 2000.

Thanks to Cleveland Orchestra Archivist Deborah Hefling for her gracious assistance in making this article possible.

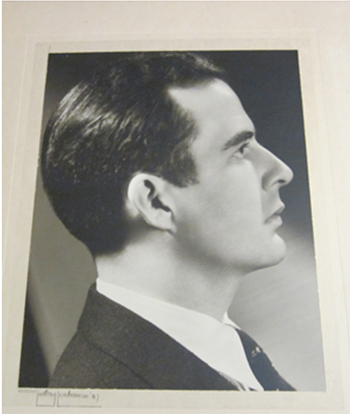

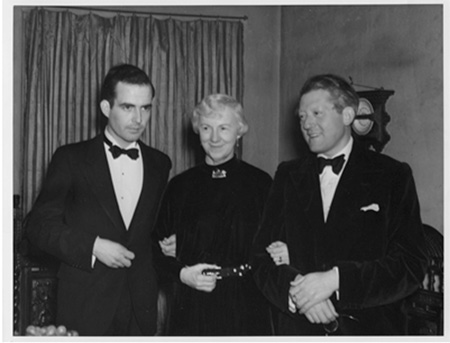

Daniel Hathaway contributed to this article. Photographs by Geoffrey Landesman courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra.

Published on clevelandclassical.com December 6, 2011.