by Mike Telin

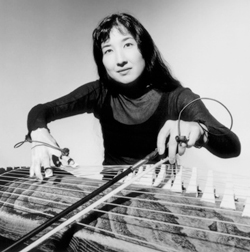

Since founding the San Francisco Gagaku Society, Masaoka has introduced new ways of thinking about and performing on the koto which include improvisation and expanding the instrument through the use of computers, lasers, live sampling, and real time processing. As a composer, Masaoka’s compositions often include the sound and movement of insects, as well as the physiological responses of plants, the human brain, and her own body.

On Sunday, February 16 beginning at 7:30 pm, you can hear Miya Masaoka in performance as part of the CMA Concerts at Transformer Station series.

Born in Washington DC, Miya Masaoka came from a musical family, “My mom played violin and a cousin and two aunts played the koto. I grew up playing the piano, but I had been exposed to Japanese music through Buddhist funerals I attended as a child.”

Masaoka says she became fascinated with the strings of the koto, because they reminded her of the inside of the piano: “being able to touch the strings as opposed to the piano where you hit the key which causes the hammer to strike the strings, so you kind of bypass a couple of steps. This was interesting to me so I asked my aunt for her old koto because she had stopped playing it, but somehow it had gotten lost so I ended up purchasing one.”

Miya Masaoka went on to earn her BA in Music at San Francisco State University and an MA in music composition at Mills College. “I studied traditional music as well as western music, which was great. There was an active Asian American music scene in San Francisco and I also got to work with musicians like Cecil Taylor by playing in one of his large ensembles. At the same time I started studying the traditional repertoire with different teachers, but I felt the strongest bond to gagaku, which is the orchestral music,” she said, adding that once a month her teacher would come up from UCLA. “I did that on and off for about seven years but I was also able to go to Japan to study with him as well.”

Her resume lists on-the-job training with Steve Coleman, Fred Frith, George Lewis, Ornette Coleman, Dr. L Subramaniam and many others, “but my breakthrough came while playing a series of concerts with Sara Sanders. From there I was introduced to different people who were involved in improvisation. From there things escalated rapidly. I was asked to be in different groups and to perform with different people.”

And why does Masaoka think the koto was embraced by musicians of such a diversity of musical styles and genres? “Well, this was in the early 1990’s, which was the age of multiculturalism. We don’t really use that term any more. But I think that was a strong part of the San Francisco scene at the time. But now with the Internet, young people have access to almost any kind of music from anywhere at any time. And they don’t have to pay for it and because of that, everything has become accessible.”

At the moment, Masaoka says she is doing a lot of composing including a piece for symphony orchestra that does not include a koto. “Still, I feel that the things I have learned by working with the koto and Japanese music have transferred themselves to my work as a composer.”

And what about her compositions that include the sounds of insects? “It’s the relationship of us as human beings to nature,” she says. “Japanese culture talks about sounds of insects and it has a special relationship to them. It talks about them coming out in Autumn and singing — there are a lot of haiku written about the sounds of the insects. There is even an instrument called hichiriki which is part of a traditional gagaku ensemble which history says was possibility created after the sounds of the cicadas and different insect sounds. So the idea of noise and sound in music is very culturally inscribed, so those things that may be called noise in one culture could be considered a beautiful sound in another.”

Again, she also believe that technology is causing the younger generation to embrace different kinds of sounds. “Hearing different sounds whether it’s on the Internet or just in daily life and the integrating of those sounds with music is something that I also enjoy doing.”

Miya Masaoka says that she will be using her large koto during Sunday’s concert. “I kind of like to have programs that include some things that are old and some things that are new. At the moment I’m still mulling over different possibilities. There will be a lot of acoustic playing and some electronics. I also like to include a short question and answer period after the performance because often people have questions. I’ve been told by people that [my concerts] are a unique experience for them. I can’t really speak on their behalf but that’s what I’ve been told. And it is something different.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 11, 2014

Click here for a printable version of this article.