by Mike Telin

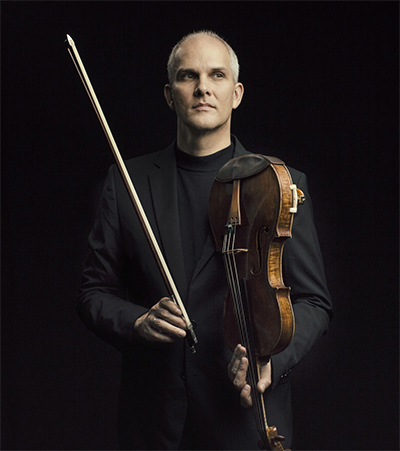

On Tuesday, March 5 at 7:30 pm at Plymouth Church, Jonathan Brown will join his Cuarteto Casals colleagues (Abel Tomàs and Vera Martínez, violins, and Arnau Tomàs, cello) for a performance of Beethoven’s monumental Quartet in c-sharp, Op. 131.

Presented by the Cleveland Chamber Music Society, the program will also feature music by Mozart and Mendelssohn. A pre-concert lecture by Roger Klein will being at 6:30 pm. Tickets are available online.

Speaking by phone from San Francisco, where later that evening the quartet would play the first concert on their eight-city North American tour, Brown said that understanding Beethoven’s Op. 131 is a lifelong process. “When we first learned it, it was overwhelming and daunting, and we thought, how are we ever going to get through this. Luckily we had to perform it, so we got through it, and then the real discovery began.”

Brown said the quartet is so overwhelming because on the one hand “it’s sprawling — 40 to 45 minutes without a break — as well as exhausting both physically and emotionally. Yet on the other hand it’s tightly composed in that you can follow the motives and the harmonic relationships between each movement in a direct and visceral way.”

Today, nearly 200 years after it was written, Brown said that there are very few, if any quartets with which it can be compared. “In the 20th century you can find some — Berg’s Lyric Suite comes close and certain Bartók quartets. But I cannot think of a piece that comes close to this in its scope, depth, humanity, humor, and pathos. We’re playing this quartet on a number of concerts on this tour. That was partly planned because we’ll be recording in March and we want it as fresh in our memory as possible.”

Tuesday’s concert will open with Mozart’s Quartet in B-flat (“Hunt”), which Brown said is most famous for its first movement. “It’s in the key of B-flat, which is the typical key of the natural horn, and the quartet has a horn motif, which is where it gets its name.”

The “Hunt” is also unusual in that it is reminiscent of outdoor music. “One associates string quartets with indoor, courtly gatherings, but this one is full of tremendous humor, especially the last movement — it’s very Haydnesque. It also has a slow movement that is unlike any in the repertoire. It’s totally unpredictable, very moving. I can’t think of another quite like it.”

The program will also include Mendelssohn’s Quartet No. 6 in f, the last major piece that he wrote before his death in 1847. “His sister Fanny died less than six months earlier,” Brown said. “They were very close personally and musically, and when she died he was crushed.”

The violist noted that unlike Mendelssohn’s typical scores, this one contains many inconsistencies, like similar passages that are marked in different ways. “He was always very meticulous about how he went through his scores. It’s by no means an unfinished work — it’s just revisions of the last details.”

The work also illustrates how the composer was anticipating Romanticism. “He came out of the Classical tradition of Mozart and Haydn, but his music was always looking forward to the later 19th century,” Brown said. “With the tremolos in the first and last movements, you can hear the Romantic Mendelssohn coming through, and there is the most touching slow movement — a sort of song without words.”

In celebration of their 20th anniversary, Cuarteto Casals embarked on a six-concert series of the complete Beethoven quartets, accompanied by six commissioned companion pieces. “The composers represented a broad overview of 21st-century composition in southern Europe,” Brown said. “We gave each of them a group of quartets and told them that they had free range to write a piece of eight to ten minutes that commented on some aspect of these works. Beyond that we didn’t give them any more instructions. Thankfully we received six very different pieces. Two were almost jazz-like in that they had some improvisatory elements. One was written in scordatura and was full of all sorts of unusual effects — sort of spectral music. One was rigorously composed around certain motives from one of Beethoven’s quartets.”

In 2018 the Casals released the first of a three-volume set of the Beethoven quartets on the Harmonia Mundi label. The second will be released in 2019 and the final group in 2020, to coincide with the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

Brown said that Beethoven is the template for contemporary composers. “As Stravinsky said about the Große Fuge, ‘It’s modern music for all time.’ Although Beethoven came out of tradition, he decided to find his own path, which set the way for future composers like Brahms. He developed entire pieces out of small musical cells, which would be unimaginable without Beethoven.”

The violist added that the Second Viennese School come out of Beethovenian traditions, as did composers like Ligeti and Kurtág. “We’ve worked with Kurtág and he said, ‘My mother tongue is Bartók, whose mother tongue was Beethoven.’ So I think he is a unique force in the history of music.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 25, 2019.

Click here for a printable copy of this article