by Stephanie Manning

LOCAL NEWS:

Youngstown State University has announced the fourth season of the Pipino Performing Arts Series, hosted by the University’s Cliffe College of Creative Arts. The six performances, one per month starting this month, will kick off on September 22 with a virtual presentation by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Lang. Learn more here.

THE NATIONAL CONVERSATION:

“A striking aspect of the former fellows, however, is how little they are like Dudamel — or each other,” writes Mark Swed. He goes on to note that out of the five conductors from the program that made their Hollywood Bowl debuts this summer, four were women — including Marta Gardolinska (pictured). “The glass ceiling doesn’t stand a chance.”

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

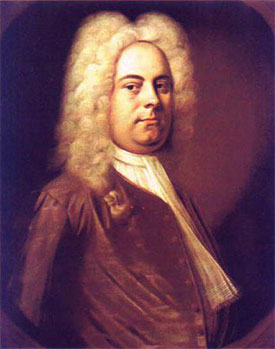

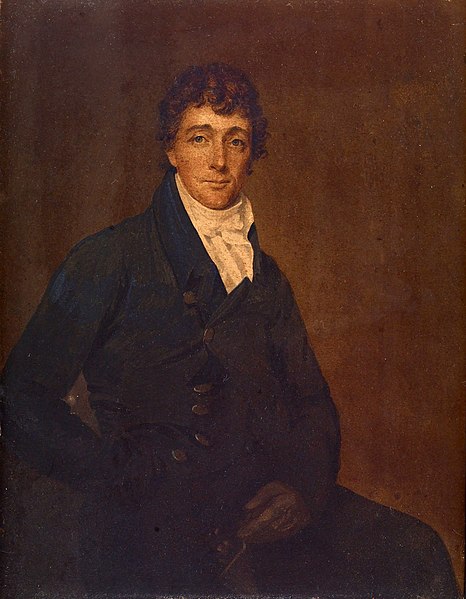

Artists, it looks like September 14 could be a good day to finish that project you’ve been working on — just ask George Frideric Handel or Francis Scott Key.

Jennens, who had previously worked with Handel on the oratorio Saul, wrote to a friend that “I hope [Handel] will lay out his whole Genius & Skill upon it, that the Composition may excel all his former Compositions, as the Subject excels every other Subject.” Surely the librettist would have been pleased to know that the composer worked on it morning and night until its completion, and that it would eventually become Handel’s best-known work.

The well-known recordings of Messiah are almost too many to list, so let’s focus on a specific type of performance that’s uniquely connected to this piece — the “sing-along Messiah.” Open to singers of all skill levels, these performances prioritize the joy of singing over musical perfection.

In Northeast Ohio, Credo Music has made a Messiah sing-along an annual tradition. Hosted at Oberlin Conservatory, this year’s event is on December 12. Learn more, and take a listen to the “Hallelujah” chorus from the 2017 performance, here.

It was not until 1931, however, that this would become the text of America’s national anthem, set to the music of “The Anacreontic Song” by a young church musician named John Stafford Smith. Notably, when President Hoover signed the new anthem into law, the wording left the door open for all kinds of arrangements and interpretations.

Over the years, the legendary status of “The Star-Spangled Banner” has led to some unforgettable performances, but also some questionable renditions. What makes this song so difficult to sing? And why is there pushback to any attempts to change it? This video by Adam Neely analyses the anthem’s history and symbolism through a musical lens.

“Like the United States, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ is flawed,” Neely says. “Those countless musicians and singers who aren’t able to account for it’s flaws will achieve a sort of crass mediocrity, but those who can transform the anthem’s flaws will rise above them — and may have in their hands the ability to achieve artistic greatness.”

Photo of Marta Gardolinska by Jason Armond