by Parker Ramsay

On East 3rd Street in Los Angeles, the showrooms at Hauser & Wirth break away from the typical post-industrial chic of the surrounding Arts District. Solid white walls and polished concrete floors bear a sheen of sterility, defiant against trends to hang art on brick walls. There is light everywhere, eliminating the possibility of shadows. Windows and ventilation grates are absent, prohibiting the passage of moving air. And so, Alexander Calder’s mobiles sit frozen, restricted from displaying the anti-gravitational nuance for which they are known. Rotational joints appear locked in place, constraining metal ligaments from separating or conjoining in motion. Touching is strictly not allowed. Attempts by children to blow air are met with reprimands from security, loaded five or six guards deep in a showroom containing only twelve pieces.

The viewer can physically move around the art, imagining the possibility of various spirals and spins, but any permutation of the sculptures’ various elements is limited by the human mind.

“Why must art be static? You look at an abstraction, sculptured or painted, an entirely exciting arrangement of planes, spheres, nuclei, entirely without meaning. It would be perfect, but it is always still. The next step in sculpture is motion.” (Alexander Calder, “Objects to Art Being Static, So He Keeps It in Motion,” New York World-Telegram, June 11, 1932.)

Indeed, ideally one would not need to walk or move around Hauser & Wirth at all, as the sculptures ought to be the ones moving. The idea surely is that the art should move on its own.

But more often than not, operas are expected to be dramas, and not just staged musical works. How can a random selection of operas from across the ages provide any narrative arc? Because of the age of the European canon, the stories that operas tell are explicitly tied to their historical and geographical contexts. Cage himself joked, “For two hundred years the Europeans have been sending us their operas. Now I’m sending them back.” But humor aside, because some European operas have taken on different meanings in the American landscape, choosing which dramas to showcase and insert into the randomized mix can be difficult.

One aria in particular in Sharon’s production highlighted the problem of trying to make an aria look and sound totally random: a housewife in black sequins swept the floor with a wooden broom as she sang “La Mamma Morta” from Umberto Giordano’s Andrea Chénier. What’s interesting is that the manner in which the soprano was presented divorced her aria from any traditional European or American readings of it. If the soprano had appeared in French Revolution-era garb, she would be roughly adhering to the intent of the composer and librettist, allowing the surrounding cacophony of the other arias being sung simultaneously to create a context by pure coincidence. Similarly, if she were to appear dressed as Tom Hanks’s character in Philadelphia, IC could allow other arias to reshape the more American pop-cultural associations of “La Mamma Morta.” One can’t help but wonder whether divorcing these operas from their histories simply reduces them down to their musical elements.

In prefacing his seminal essay Opera as Drama, musicologist Joseph Kerman noted that, “Throughout the history of opera, if not quite continuously, there have been some who have taken opera’s dramatic potential seriously and others who have not.” Though perhaps putting up a straw man, Kerman’s essay raises an important question: what can opera be without drama? And in stripping away stories and teleologies, what is it that makes Cage’s work an opera rather than a work of performance art that is operatically derivative?

Perhaps it is up to the audience to decide themselves what the drama “is.” After all, it’s inherent in the title: Europeras is pronounced “Your-operas.” If anything, the audience may in fact be the most unpredictable variable, and the discombobulation of drama is likely produce an enormous variation in audience response.

But who is the audience in that case? If Cage’s goal was to “send” European operas back, why deconstruct them to a level of historical unintelligibility except for the purpose of confusion for its own sake? For those who believe in opera’s dramatic primacy, the abandonment of drama may add layers of intentional disregard for opera’s European legacy. Cage’s project was not absurdist nor a mere parody. It was a conscious trans-Atlantic attempt to use the I Ching as a means to combine several European operas at once.

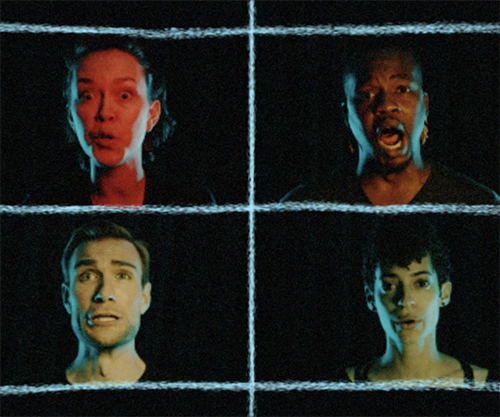

In Sharon’s production however, there were points at which an American audience was clearly being catered to. That’s not unsurprising as the performance took place on election night. On two occasions when the audience was united in laughter rather than continually dwelling on their own experiences, it was as if the I Ching was stopped dead in its tracks. At one point in Europeas I, a soprano stood at a whiteboard with blue and red markers, coloring in states on a map as she looked at her iPhone. In Europeras II, an African–American baritone stood behind a lectern as a skull and bones flag waved in the background, making vague reference to the American political legacy of societies such as Yale’s Skull and Bones. While humorous and pointed, both broke with the theme of randomness, marking an injection of willful timeliness.

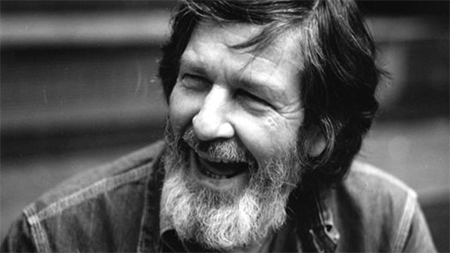

Arguably, Sharon and Industry Opera didn’t so much present Europeras as they did “Theiroperas.” Explicit political references and messages fly in the face of Cage’s lifelong project to elevate music beyond human intellectual limitations. Even in the years before his first experiments with the I Ching, Cage sought ways to avoid intent, idea, and active cognition. Indeed, in composing music for Herbert Matter’s documentary Works of Calder (1950), Cage confided to Pierre Boulez that he found difficulty in being able to appropriately compliment footage and sound clips of Alexander Calder’s kinetic sculptures.

(Letter to Pierre Boulez, Jan 17, 1950)

I have just finished recording my cinema music. I started that piece of work in a dream: I wanted to write without musical ideas (unrelated sounds) and record the results 4 times, changing the position of the nails [in the piano strings] each time. That way, I wanted to get subtle changes of frequency (mobility), timbre, duration (by writing notes too difficult to play exactly) and amplitude (electronically altered each time). But I found musical ideas all about me, and the result would have been no more than simple. The adventure was halted by machines which are too perfect nowadays, They are stupid… Even so, I had fun in the 2nd part by recording noises synthetically (without performers). Chance comes in here to give us the unknown.

Like Calder’s stationary mobiles at Hauser & Wirth, Cage’s Europeras were forced into stagnation, succumbing to the human impulse to make sense of that which surrounds us. In dispensing with dramatic elements and adding their own interpretations, Industry Opera beckoned audience members to join the director and company in compensating for the cacophony, moving their minds around that which might seem strange or unrelated. Cage and Calder’s enterprise was the emancipation of art, so as to allow it to move. Their work ought not to be constricted.

Parker Ramsay is a musician and writer living in New York. He is a staff writer for VAN Magazine (Berlin) and runs a blog, “Harping On: Thoughts from a Recovering Organist.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com December 4, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article