by Mike Telin

The program, conducted by Benjamin, also includes Dieter Ammann’s glut, Oliver Knussen’s The Way to Castle Yonder, and Maurice Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye (complete ballet). Performances take place on Thursday, February 15 at 7:30 pm and Saturday the 17th at 8:00 pm at Severance Music Center. Tickets are available online.

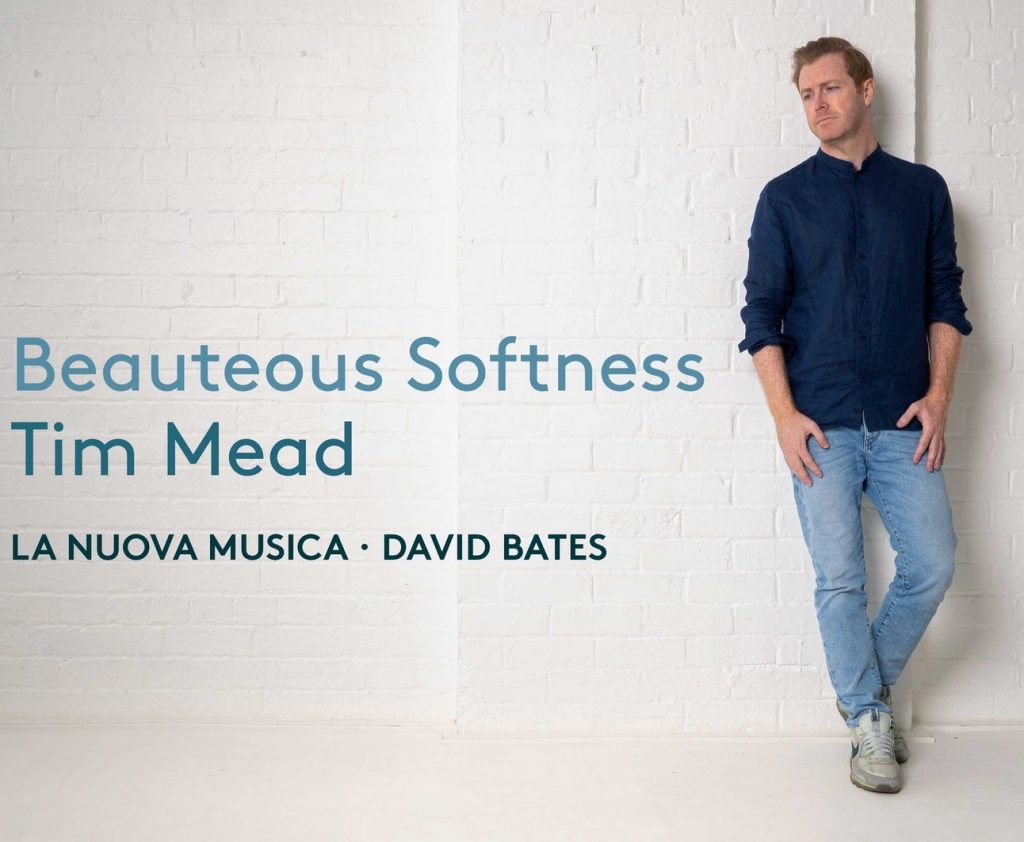

I caught up with Mead over Zoom to discuss Benjamin’s song cycle, his passion for Purcell, and his quick transition from the choir to the opera stage. (Photo by Andy Staples)

Mike Telin: This week will be your Cleveland Orchestra debut.

Tim Mead: Yeah, it’s my first time in Cleveland. I’ve not been to the States a lot in my career. I’ve done some operas in Chicago, St. Louis, Philadelphia, New York, and a little bit in San Francisco. But it’s a real pleasure to bring a piece like this to Cleveland.

MT: How did you become connected with the piece?

TM: I’ve been connected with George Benjamin for many years because I was part of the first set of productions of his opera Written on Skin. And I’ve done, I think, ten runs since. I also sang Dream of the Song with him in Frankfurt in 2019, so this will be only my second time performing it. And it’s a great joy for me to come back to it.

MT: This piece has an interesting musical language.

TM: Having become so immersed in George’s language with Written on Skin, it feels quite cohesive to me. Everything he writes for voice comes from a deep and natural understanding of text. As a singer, once you get past the written complexity of it — how it looks on the page — there’s a naturalness to his lyrical writing. And when done the way George wants it to be — he’s very particular about getting the proper nuance — it feels very organic.

MT: Would you mind walking me through some of the movements?

TM: Sure. As I said, George writes for the voice incredibly well, better than any modern composer I’ve worked with. And if you know his vocal writing, you notice that he hardly ever uses melismas — he’s very note-per-word, note-per-syllable. And yet the first movement, “The Pen,” opens with this huge, violent, and quite complicated melisma that is probably the hardest thing in the piece to sing.

And George never does anything without the deepest of thought. It’s supposed to be the brush stroke of an elaborate calligraphy, because he’s talking about the violence as well as the beauty and potential of the written word. It has a sort of violent flourish, almost like the movement of a saber or a sword, which I quite like.

It also takes you right back to the way we use the voice in the Baroque. It’s a complex figure rhythmically and tonally with this sort of flamboyance that was the bread and butter of my voice type back in those times.

One of the features of George’s writing that I like a lot is the way he uses a big orchestration, and big clashing noises that dissipate in a second — and you’re left with this sort of aural halo in which the voice can become so intimate and so clear. He never leaves you fighting for space within the sound. That’s a great skill of his as a writer for the voice.

Another one of George’s skills is his ability to write beautifully and sensually. And I think the most sensual movement in this piece is probably “Gazelle,” which I love just because, when are you ever going to sing the word gazelle again? And to make this sort of weird creature the subject of such dripping sensuality is quite remarkable.

Then you have things like the final movement, “My Heart Thinks as the Sun Comes Up.” I’ve talked about the intimacy of George’s writing, but this involves the entire instrumentation and the female chorus, in this expansive meditation on the universe. None of it’s loud or brash even though he’s got the strings and a whole array of percussion, like he always likes to use, along with great solo contributions from the horns and the oboes. And with that palette he creates this sense of vastness, which I think is quite special.

MT: I love the way you describe it. It’s one of those pieces that I wanted to listen to again because it is so detailed.

TM: I think that’s the joy of the piece. I mean it as a compliment when I say that George’s music is beautifully manicured. There’s all these little details, and when you work with George, he’s always on you about those little details, because they do really mean something. The difference between a dotted rhythm and a triple rhythm actually tells you a lot about what he’s trying to say.

TM: Purcell is my favorite composer — this is my second album of his work, and I have a feeling there might be another one. I just love immersing myself in that repertoire — for me it’s the same sort of relationship that singers of later repertoire feel with the Lieder of Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms.

I love the way I can use language with Purcell — there’s quite a lot of freedom within those Baroque structures. I particularly love things on ground bass, because it feels improvisatory, almost jazz-like riffing. At the end of the day, it’s just beautiful music, and I’ve always been a sucker for beauty. I think that’s why I relate so well to George’s music.

I was talking about the album just the other day in an interview — I went deep into the melancholy aspect of it, which is sort of an Elizabethan sensibility. I think that inspired some beautiful and really simple music, yet there’s so much that you can get from it. I think it still has the power to move and engage us years later.

MT: You started singing quite young. When did you decide that you wanted to be a singer? And when did you say, I am a countertenor?

TM: I’ve always said, and I maintain to this day, I never made a conscious decision that this was going to be my career.

I’d been a singer since I was 7 in a pretty professional context, and becoming a countertenor was purely an accident. I’d sung treble in my cathedral choir until I was 14. And then about 15, an American countertenor in the choir had visa problems and had to go home. So there was suddenly a vacancy, and my choirmaster asked me if I’d like to try singing countertenor, which I had never done before. So I did for about four weekends, and he said, you’ve got the job.

I did that for three years and then won my scholarship to King’s College Cambridge, and it all sort of went from there. When I finished at King’s I fully intended to be a lay clerk at Westminster Abbey or something, but I happened to meet an opera manager who persuaded me to go to music college and then represented me. And within two years, I was on the opera stage with William Christie. So it just happened.

MT: You’ve been on the stage with some pretty good people, even from the beginning.

TM: I’ve been lucky, especially with my career in France with Bill [Christie] and Emmanuelle Haïm. And I just finished a project in Amsterdam with Ottavio Dantone, who’s a great Italian harpsichordist-conductor.

But I always attribute most of the things I learned to people like Bill Christie and Emmanuelle Haïm, and then in England to Laurence Cummings and Christian Curnyn. And they are four quite different conductors. But what I learned from Bill was to always put the expression of text at the forefront. Of course there’s a ton of stylistic information I’ve picked up from those brilliant people over the years.

But at the end of the day, because of the way I’ve been educated, I don’t rely on scholarly advice. I’ve been immersed in this music for over twenty years now so I think I’m allowed to trust my instinct a little bit.

I think I was put off a bit because when I did my undergraduate degree at Cambridge University. I remember being quite frustrated by a Handel scholar there — we disagreed on basic things like the speed of arias. He was a very clever, smart man who knew more about Handel than I could ever know — but I was the one doing it, and he was the one writing about it. I’m not saying the two things can’t mix. Both are equally valid, just different. And that’s not to discredit the historical movement at all, because it’s been so vital to help us understand the gestures. I think we should use all the information we have to make these pieces our own.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 12, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article