by Donald Rosenberg

Reposted courtesy of ChamberFest Cleveland

In the end, it’s all rhetorical. ChamberFest audiences this year will be the beneficiary of glorious repertoire performed by stellar artists, whether or not the philosophical question of thematic priorities can be answered. What’s for certain is that co-artistic directors Diana Cohen, Franklin Cohen, and Roman Rabinovich are always on the lookout for a concept that will help them devise coherent, meaningful, and engaging programs.

A title is “always a jumping-off point for us to be thinking in a certain direction,” says Diana Cohen, “and then all kinds of other suggestions come through because of personnel or instruments or different considerations. It’s just a beginning.”

For Rabinovich, “Sacred + Profane” provides “a timeless theme.”

No one could argue that the programs achieve the intended goal. Seeking flexibility within the potential paradox, the co-artistic directors have come up with a keen balance of works that embrace the “sacred” and “profane” (or secular) implications of the music. While Debussy’s magical Danse sacrée et Danse profane, for harp and strings, would appear to have been the principal inspiration for the season, the theme was considered long before this work was added to the festival repertoire.

The season heads onto paths that couldn’t remotely be considered conventional. There is ample cherished and familiar music (including selections from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, in an arrangement for two pianos, and so much more). But the repertoire mostly diverges from the mainstream and iconic, throwing arms around a bounty of neglected or, at least, infrequently programmed music that will expand everyone’s listening horizons. The repertoire takes a break from Beethoven and Haydn string quartets – but includes foursomes by Adams, Stravinsky, and Suk – and revels in quintets (11, to be exact – the majority likely to be new to most audience members).

The same could be said, to different degrees, of all of the pieces ChamberFest will present this season. They are prime, sometimes surprising, always absorbing epitomes of the most ineffable of the arts, with their own languages that touch us in ways words could never adequately convey. For those of us hooked on Mozart and Debussy and colleagues, the most accurate definition of heaven on earth – sacred or profane – is music.

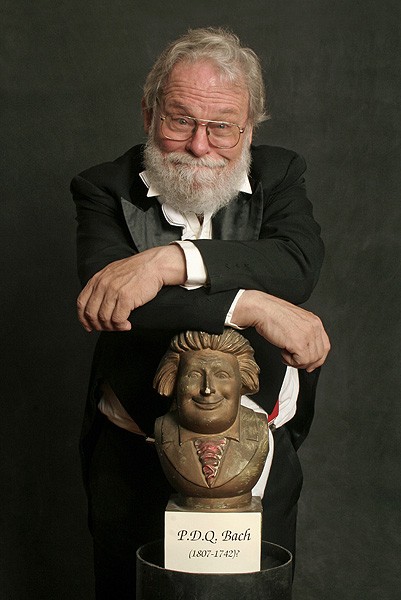

The treasures will pour forth this season from the pens (or computer screens) of 42 composers – seven of them living, one of them imaginary, from 10 nations. Imaginary? Along with the presence of real Bachs (Johann Sebastian and son Carl Philipp Emanuel), we will have the possibly dubious experience of hearing a (mercifully) short work by Peter Schickele’s loopy “alter ego,” P.D.Q. Bach (1807–1742)? (The question mark is Schickele’s.) In the case of this doltish composer’s “Little Bunny Hop Hop Hop,” S. 4: No. 1, we go beyond the profane and into the sphere of the irreverent and the ludicrous (wait until you see the props!).

Among the season’s notable sacred entries, the most resplendent is the Bach cantata, while others of spiritual resonance include Biber’s Mystery (Rosary) Sonata and Palestrina’s “Dominus Jesus in qua nocte.” For a melding of the sacred and the profane, no work could be more startling than Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, whose innovations and mysteries will throttle the ears in a version for two pianos and percussion.

Whatever spiritual, psychological, or emotional impact the season’s works have on listeners, they share the miracle of artistic imagination and prowess – and the ability to take us beyond everyday life.

“Humans have an innate urge for transcendance,” says Rabinovich.

To which grateful ChamberFest musicians and audiences can only say: Amen.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 30, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article