by Mike Telin

As part of the Oberlin Artist Recital Series, Jeremy Denk will perform a program that celebrates women composers from the 19th to 21st centuries along with works by Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms on Thursday, November 30 at 7:30 pm in Finney Chapel. Tickets are available online.

Since graduating in 1990, establishing a career that encompasses “a lot of different things” is exactly what Denk has gone on to do. He is the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship and the Avery Fisher Prize as well as being admitted to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. This season he will premiere a new concerto written for him by Anna Clyne, return to Wigmore Hall for a three-concert residency, and collaborate with the Danish String Quartet. His latest album of Mozart piano concertos, released in 2021 on Nonesuch Records, was deemed “urgent and essential” by BBC Radio 3.

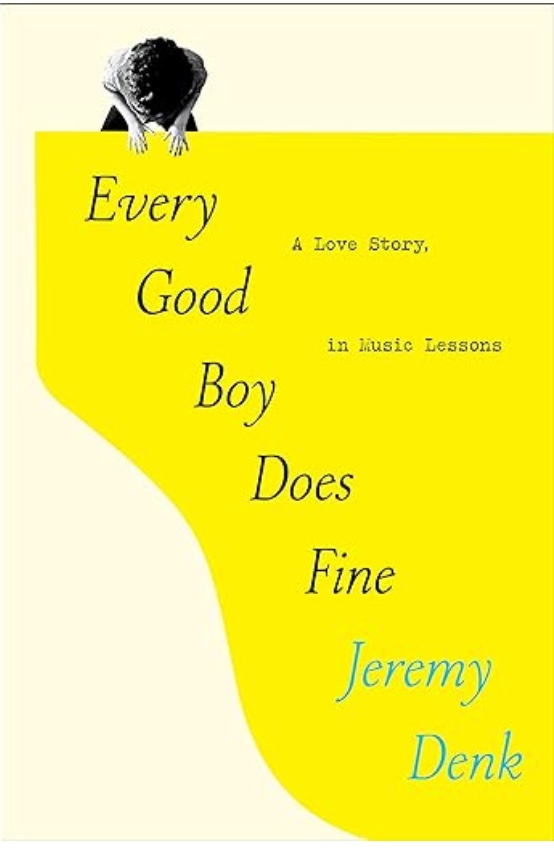

As a writer, his New York Times Bestselling memoir — Every Good Boy Does Fine: A Love Story, In Music Lessons, published by Random House in 2022 — was featured on CBS Sunday Morning, NPR’s Fresh Air, The New York Times, and The Guardian. Denk wrote the libretto for the comic opera The Classical Style: An Opera (of Sorts) with music by Steven Stucky, and his writings have appeared in The New Yorker, The New Republic, The Guardian, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and on the front page of The New York Times Book Review. His blog, Think Denk, is archived at the Library of Congress.

I caught up with Jeremy Denk by phone and began our conversation by asking him to talk about his Oberlin program.

Jeremy Denk: I had learned Tania León’s Rituál, and I thought it was an astonishing piece that is full of imaginative and interpretive choices. And I had played a piece by Missy Mazzoli that I loved, and I wanted to learn another, so I started working on Heartbreaker. It was then that I started to think about pairing them with works by other great women composers. Once I started to make the set, I thought, ‘Oh, where should we go from here?’ So it was like curating an iPod shuffle list.

Mike Telin: What attracted you to Meredith Monk’s Paris?

JD: I’ve met her a couple times. She’s an amazing singer and she represents, let’s put it this way, a different outlook from many quote-unquote conventional composers. And like Missy, there’s some aspect in her that is sort of refusing to accept the terms of the norm. She’s also such a generous and honest composer.

I love this little piece, Paris, and I thought it would make a nice pairing with Louise Farrenc’s Mélodie in A-flat Major, which is a gorgeous tune that is full of feeling.

Like the Meredith Monk it appears to have a very simple premise. It may seem like a gentle salon piece — I hate to use that word — but as you play it, there’s some magic that unleashes with colors.

MT: I was really happy to see some music by Phyllis Chen on the program. She’s also an Oberlin grad.

JD: This piece, Sumitones, is a knockout. I mean, I am in love with it. It’s written in graphic notation — some of the notes are in lighter shades and some are in darker, which is to reflect the art of calligraphy, where you draw certain gestures starting with a dark ink and then let the pen glide over the page in lighter shades. It’s a kind of a dialogue between those two things.

I want to avoid suggesting that male composers have been influential here, because this piece is absolutely its own thing. But in the best way, I feel like it has some little hints of Ives floating through. And right after, I’ll play Five Improvisations by Amy Marcy Cheney Beach.

MT: Ruth Crawford Seeger, what a talent.

JD: I agree, and her Piano Study in Mixed Accents is just an astonishing knockout of a piece. It’s very short and very hard. To my ear, it has a lot of bebop and jazz qualities. So it’s kind of a modernist piece with a smile.

And Chaminade’s The Flatterer — I couldn’t help putting Flatterer and Heartbreaker on the same program for whatever reason. And Clara Schumann’s Romance is kind of a semi-memorial for Robert. It’s fused with grief and little tokens of his music. And if you know both of their lives, you know that it is her speaking to him.

MT: And why include Robert Schumann’s Ghost Variations and Brahms’ Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel?

JD: As I started to look at Robert Schumann, I thought, what a tremendous figure of the 19th century he was, along with Brahms. And those two clustered around Clara in a meaningful way. I think that they both depended on her. And I wanted to imply, without saying it, just how much the music of the 19th century owed to women, whether we pay attention to it or not.

JD: It’s a long story, but I’ll make it short. I wrote a piece for The New Yorker which was well-received, and then they asked me what I’d like to do next. I really wanted to write about György Sebők, who was such an incredible figure and teacher. And that was also very well-received, even more than the first. And that’s how I ended up with a book deal — they came to me and said, “We want you to write something bigger that will fill in a lot of the gaps.”

I was terrified. I tried to explain to them that a lot of piano lessons are very boring, and it’s not all page-worthy. So, I got the book deal and I was a little freaked out, and then gradually I managed to sort of tell myself to be honest. I’ve had a lot of amazingly great teachers over the years — maybe more than your average musician. I went to school for such a long time, and it felt good to remember things. And I feel comforted and encouraged that some young people seem to be getting a lot of pleasure out of it.

One of the trials of writing it — and I’m not sure if I totally succeeded — was writing about myself. After a while I was like, ‘Oh God, I’m so annoying.’ But once I started, for example, writing about Norman Fischer and how he talked and his laughter, or when I talk about Sebők, that was easy — those pages flew by.

MT: I went back and listened to the entire show that you did with Terry Gross on Fresh Air. That was so much fun.

JD: I’m so grateful to her. She comes to my concerts in Philadelphia from time to time, so she knows me a little bit. And it goes without saying that she’s a great interviewer. She honed in on certain things in the book that I wouldn’t have thought of.

MT: Well, Jeremy, is there anything else you’d like to tell me? If not, this has been, again, just a fascinating conversation.

JD: No, I’m good. I think I talked myself out. I’ve got to get back and practice Tania León.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 28, 2023.

Click here for a printable copy of this article