by Mike Telin

In the effort to “connect” with their audiences, classical musicians have dug into their creative souls and are now using the Internet to share their own thoughts on music, as well as a variety of other topics, with the public. I am thinking especially of Jeremy Denk’s witty blog “Think Denk: The Glamorous Life and Thoughts of a Concert Pianist”. At this time of this writing, Joshua Bell’s Web site said that he had 641 fans currently on-line. One can also learn about the non-musical enthusiasms of cellist Steven Isserlis on his Web site, and pianist Stephen Hough now has 2,404 Twitter followers. The Cleveland Orchestra’s principal flutist, Joshua Smith, has been making regular Facebook postings about the new Jörg Widmann concerto he will be premiering at the end of May. Other Cleveland Orchestra members we are aware of who have Web sites and blogs include Barry Stees, Eliesha Nelson, Frank Rosenwein, Franklin Cohen, Massimo La Rosa, and Michael Sachs.

Will there come a time when classical musicians can rival Lady Gaga’s 173,000 Facebook likes? I am not sure, although Cleveland Classical.com contributor and blogger Timothy Robson (whose day job is deputy director of the CWRU Library) told me that after tweeting from a Lady Gaga concert in Milan, he picked up a lot of new Twitter followers as a result. Although he went on to say, “I’ll bet they were really surprised when I went back to my usual Twitter stream of classical music and library topics.”

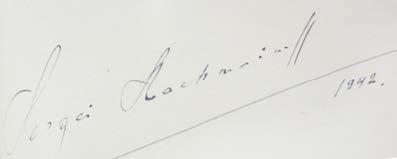

All of which makes one wonder how feature writers prepared before we had the ability to Google someone’s name and have at least five to ten articles about that person appear on the screen in front of you? Looking forward to The Cleveland Orchestra’s next set of concerts, when Horacio Gutiérrez will play Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto — what would the eminently famous Sergei Rachmaninoff do to connect with his fans if he was living today and had access to Web sites, blogs and Twitter? Or did he have his own means of promoting himself in his own day? A recent visit to The Cleveland Orchestra archives at the invitation of the Orchestra’s archivist, Deborah Helfing, turned up some fascinating material relating to Rachmaninoff’s personal appearances with The Cleveland Orchestra. (Rachmaninoff’s autograph, above, courtesty of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives).

Early on, it took impresarios like Adella Prentiss Hughes — at the time the only female manager of a major symphony orchestra — to create the hype for an artist and to fill the concert hall with patrons. Advance publicity for the 1923 appearance promised that the concert would “be an occasion to mark musical history in Cleveland”. The pairing of two eminent Russian artists — and friends — would provide the audience with a glimpse into “the cosmic soul of Russian music”, and Sokoloff was considered to be “one of Rachmaninoff’s foremost interpreters in the orchestral world” (2000 article by Carol Jacobs, courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives).

By the 1940’s management companies had developed elaborate publicity materials for their artists. In 1940-1941, NCB Artists Services produced “Press Materials on Sergei Rachmaninoff” (courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives) — preceding his last two Cleveland appearances. The collection includes eighteen human interest stories for local managers to customize and distribute to the local press. Story topics include: “Electric muff keeps Rachmaninoff’s hands warm”, “Four pianos taken on Rachmaninoff tour”, “Rachmaninoff not gloomy, his family says” and “Rachmaninoff was once ‘a lazy, mischievous boy”. The management adds, “It is suggested that only one story be sent out at a time”.

Other story titles require a bit more explanation. “Rachmaninoff never satisfied with his own works, is continually revising them” goes on to note that “the composer spends days during the summer months working over them” and that “newspaper critics occasionally chide him because he does not play the C Sharp Minor Prelude the way it was written”.

Rachmaninoff responds, “I have revised it since it was published”. The story ends with the fascinating non sequitur, “As relaxation from his composing and revising, Rachmaninoff spends part of each day during the summer on his speedboat…He is no good as a mechanic and can’t make repairs if anything goes wrong. But he loves to pilot his boat about Long Island Sound where he now spends the summer”.

In “The audience never errs” the composer says, “Taken individually the people in an audience may all be poor critics of music, but as a complete body, the audience never errs. It is never wrong in its reaction to a performance”. On the other hand, Rachmaninoff noted that he never considers the audience’s taste in drawing up his programs. “No, I think only of my own taste”.

Further to the “Rachmaninoff not gloomy” story, Sofia Satin, his sister in law, explains “In public he is modest and reticent, and people think he is gloomy. But he really has a wonderful sense of humor and can laugh heartily”.

Amplifying on the title “Play my music just as you choose, says Rachmaninoff”, the composer asks himself, “Have I any special feeling as to how other pianists should play my compositions? To be quite honest, no…especially if I am not there to hear them!”

And what about that Lazy Boy story? “We have his word for it that as a boy he persistently shirked his piano practice. He much preferred to go skating or to amuse himself with the exhilarating sport of jumping on and off moving trams”. The tendency persisted after he went off to study at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, for “he very soon discovered that even if he did not practice, he played better than his more plodding but less gifted companions”. Laziness led him to develop his improvisation skills. When his grandmother asked him to play for her guests at tea time, he couldn’t remember the pieces he was supposed to study, so he improvised works of his own and attributed them to well known composers. “I knew the ladies would not know the difference”.

That sense of mischief persisted into Rachmaninoff’s later years. Nikolai Sokoloff’s Reminiscences (unpublished manuscript courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives) recalls a visit Sokoloff paid to Rachmaninoff’s villa in Rarbouillet in advance of the pianist’s 1932 performances in Cleveland. Upon arrival, Sokoloff asked Rachmaninoff if he could “wash his hands”, and was pointedly directed upstairs to the door on the right, not on the left. When the conductor pulled the flush handle, the plumbing tinkled forth “The Carnival of Venice”, a tune Sokoloff whistled as he re-entered the drawing room, producing riotous laughter from the usually melancholy host. The curious device turned out to be a gift from piano mogul William Steinway, who, thinking Rachmaninoff was usually too serious, repeatedly sent him jokes.

All of this information would make good fodder for Facebook entries, blog posts and a whole series of tweets, all to keep the Rachmaninoff fan base apprised of important personal details.

Daniel Hathaway contributed to this article.

Published on clevelandclassical.com March 23, 2011