by Nicholas Stevens

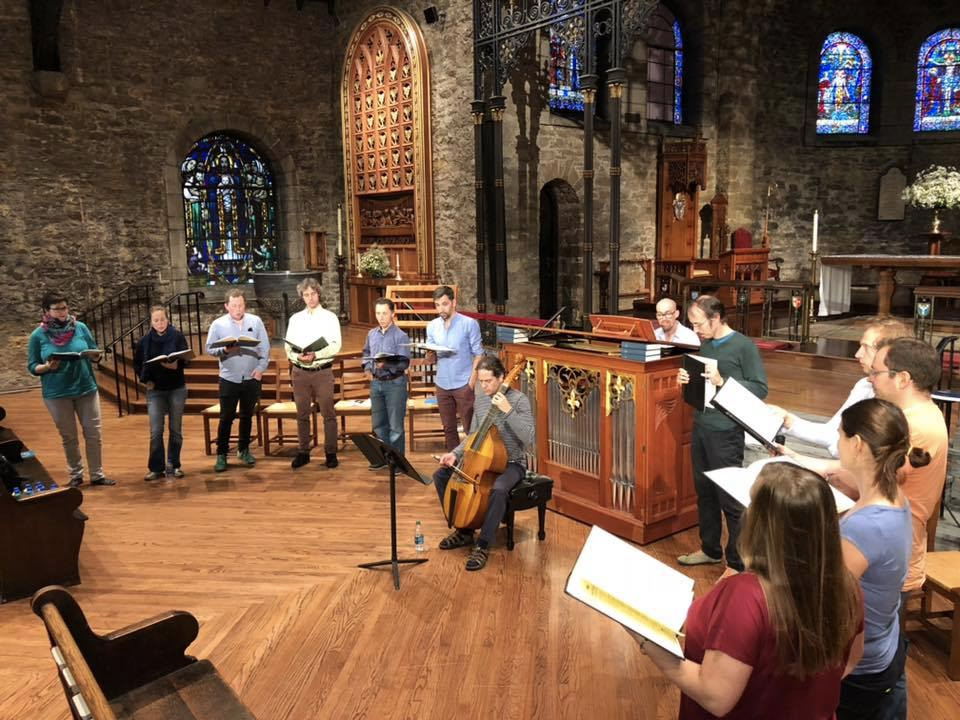

For the concert in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Gartner Auditorium on Wednesday, October 24, director and bass Lionel Meunier brought along an organist and a violist da gamba with his eleven fellow singers. Encore aside, the program focused on pieces for voices and basso continuo from the manuscripts of J.S. Bach. For each of these sacred works, Bach used the label “motet,” a notoriously slippery genre across its history. The pieces’ durations and vocal forces vary, and so, accordingly, did the number of singers onstage at any given moment in the concert.

Before each motet, organist Anthony Romaniuk supplied a prelude to foreshadow the mood of the following text, and to cover personnel changes. These were often adventurous: his musical introduction to the self-abasing Ich lasse dich nicht, du segnest mich denn, for instance, began with a startling dissonance and wandered in grim contemplation from there. Much like the singers, he and gambist Ricardo Rodriguez Miranda played with profound attention to detail while abstaining from flashiness. Like the Lutheran musicians who first performed these pieces, all involved demonstrated a self-effacing loyalty to a higher purpose: for Bach, God. Here, art.

And those voices! The first motet, Singet dem Herrn ein Neues Lied, hummed with energy from its first moments through its toe-tapper of a final fugue. Gentle swaying and shifting moods made Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf feel like the partly-cloudy answer to this burst of sunshine, and the death-fixated Komm, Jesu, komm came with haunted musical moods suited to dark October days. The passage from the Book of Genesis that opens Ich lasse dich nicht — the only piece on the program for which the attribution to Bach remains uncertain — prompts the composer to write repeating, incantatory statements. This leads in turn to a fugue on a Lutheran text, which continually hits the harmonic skids.

For a piece with “joy” in the title, Jesu meine Freude, which calls for ten singers, spins out a complex series of musical and emotional states over the course of eleven varied movements. Though the ensemble adapted its delivery to the imagery in the text — forceful declamations of the repeated word Trotzt, or “defiance,” for instance — it kept these gestures tasteful and subtle.

Johann Schelle’s setting of the Komm, Jesu, komm text for full twelve-voice ensemble made for a gorgeous encore. To single out each singer in the group for praise would be to miss the point of this singular vocal collective, and in any case, they merit more than a glance in a review. For your own sake and that of art, dear reader, look them up; they may be the best at what they do.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 30, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article