by Timothy Robson

Galak Tika draws membership from MIT students, staff, and the community, learning the traditions of Indonesian gamelan, as well as commissioning new works for the ensemble. The concert consisted of two works by Harrison as well as a new work in tribute to him by Jody Diamond, his gamelan teacher and one of the leaders of Gamelan Galak Tika. The group played on two different gamelans of Harrison’s own design and construction.

With roots that can be traced to at least the 12th century, a gamelan is a collection of instruments, primarily metallophones, xylophones, and gongs played with mallets, but also including plucked string instruments. A hand-played drum sets tempo and rhythm, and leads transitions from one section to another, while another instrument cues melodic sections. The musicians play without scores.

The solo violin plays almost non-stop through the seven short movements, often in music based on a pentatonic scale, and sometimes in modes resembling early Western polyphony. The work, which has ritualistic elements, is written in Western classical notation, and includes different textures of gamelan in each movement, sometimes very sparse, other times fully rhythmic.

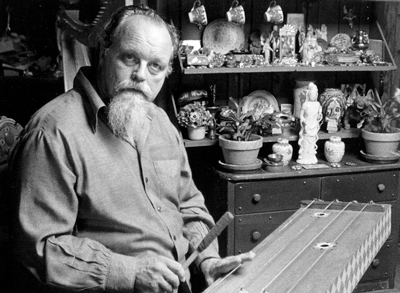

Jody Diamond’s brief At Lou’s Table was begun in 1982 as she was teaching Harrison about gamelan performance practice. She sketched much of the piece, but set it aside until 2017, when she returned to the melodic elements and combined them into a full-scale work for large gamelan — in this case Harrison’s own Gamelan Si Betty, of which Diamond is the proprietor. A typical Javanese gamelan, it also includes designs based on the American Pennsylvania Dutch, with vivid blue, orange, and white colors. To the listener steeped in Western music, the progress of the piece is clear. But with no conductor and the musicians not focused in any central direction, it happens almost by magic. Harrison’s music on the program is his own idiosyncratic synthesis of styles, while Diamond’s work, although brand new, is steeped in traditional Javanese traditions.

The work is thoroughly developed in a concerto form, at times pitting the piano against the gamelan, and at other times incorporating it into the texture as another percussion instrument, but one with wider melodic and dynamic range. The second movement has elements of a rondo, with a repeated refrain separating distinct sections. The third movement begins without discernible pause, with the full ensemble, especially the drums, adding variations to the pulse. Cahill gave a fluent, technically brilliant performance. She caught the changes in mood within the movements, and her coordination with the gamelan was spot-on.

Following the concert, Ziporyn, Cahill, Diamond, and Tom Welsh, CMA’s director of performing arts, held a lively panel discussion about Harrison’s development as a composer for gamelan, and his place as an important West Coast composer. Bravo to the Museum for sponsoring this glimpse into music too rarely performed.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 24, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article