by Mike Telin

Saturday, February 6 at 1:30 introduces “Decentering the Canon in the Conservatory.” Moderated by Chris Jenkins, the symposium is the result of conversations held by Conservatory faculty over the summer of 2020 — talks dedicated to responding to the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and other tragedies linked to systemic racism. The event is presented as part of the Richard Murphy Musicology Colloquium.

The panel includes (clockwise from upper left):

- Naomi André, professor of humanities at the University of Michigan and author of Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement

- Loren Kajikawa, associate professor of music at George Washington University and author of Sounding Race in Rap Songs

- Imani Mosley, assistant professor of musicology and music history at the University of Florida and author of “Say Her Name: Invocation, Remembrance, and Gendered Trauma in Black Lives Matter” in Performing Commemoration: Musical Reenactment and the Politics of Trauma

- Kira Thurman, assistant professor of Germanic languages, literatures, and history at the University of Michigan and author of the forthcoming Singing Like Germans: Black Musicians in the Land of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms

Jenkins said that as a Black person who plays classical music, he was taken aback the first time he heard the term “white supremacy” used to describe classical music.

“I first heard it used that way when I arrived at Oberlin in 2014. At the time, I thought, ‘this is crazy,’ but after hearing it repeated for a few years, and talking to students and faculty to understand what they meant, I came to believe it was an accurate representation of what happens in classical music.

“That’s my Oberlin perspective and it’s always useful for me to remember that most of the world is far-removed from that perspective. For many people it is the first time they are hearing these terms and we really do need them to be defined. People need a careful entrée to this world of new ideas so that they are prepared to be receptive.”

He also added that there are structural issues in the arts world that reflect and reinforce societal problems. “It will be valuable if we can talk about how to change those structures.”

Plank went on to say that when you talk about the canon you’re also talking about choice. “We need to be aware of how the choice to include something in the canon was made. As we broaden the canon, we nurture the skill to enable more choices and show a broader menu from which to choose.”

What it means to be an active, fruitful, and engaged musician in the 21st century has changed dramatically, he said. “We need to change the way we teach — and what we teach — to respond to that. At Oberlin, I think we’ve been glad to see whatever comes our way as an educational opportunity.”

“Ultimately, we chose panelists we found to be especially interesting and likely to be able to create a discussion. The members of the committee knew some of the speakers personally, but all knew of them from their recent work.”

McGuire pointed out that André and Thurman work together at the University of Michigan, and André and Mosley both work in the field of opera studies. “And like these three, Prof. Kajikawa’s work focuses on the intersection of race and politics.”

The conversation around “Decentering the Canon” is not only for schools of music. Chris Jenkins said it is extremely relevant to the average music listener as well. “We are aware that America is going to become a majority minority nation by the mid-21st century, and I think the entirety of our culture is grappling with what that means.”

He said that adapting to these changes requires more than recasting a film with actors who represent marginalized groups. “It’s beyond simply saying that the composers will be black, where before they were white — many aspects of the concertgoing experience will have to change. The question of how and why is entirely up to those who want to be part of the process. The average classical music listener can choose how to engage with that process, and what that will mean for them.”

Where does this discussion go from here? “Discussions about the canon aren’t new,” Plank said, “but there’s a high degree of urgency about the conversation at this particular moment. What we choose to teach says much about who we are and who we want to be. We would hope that the outcome will be a more just, fairer world, mirrored in our musical lives.”

What do Jenkins, Plank, and McGuire hope people will take away from Saturday’s discussion? “There is an old adage, stated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, that Music is the universal language of mankind,” McGuire wrote. “Far too frequently, this sentiment has been weaponized, and interpreted by people to mean that a certain kind of music — Western classical music — is somehow both ‘universal’ and ‘superior’ to other musics.”

He added that the culture of “genius” inscribed by this perceived universality has historically excluded anyone who was not white and male. “This inscription happens in many places, including the music history classroom and the classical music concert hall. This doesn’t have to happen. In 2021, it shouldn’t happen. Through this discussion, I hope that attendees will see that this exclusion is detrimental to a living, breathing, just, and relevant art. That, and we have a lot to do to make classical music an equitable space.”

Plank said that he thinks anyone listening to this symposium is going to come away with a broader perspective on the issue and an appreciation for what that can do for our lives. “Understanding how choices get made will nurture the reflection on who we are, and what we want to be.”

Jenkins’ hope is that people will find the symposium to be an effective point of entry into the world of the panelists’ ideas, and help prepare them to begin to consider those ideas. “I’m very sensitive to the fact that the moment you start using words like ‘systemic racism’ and ‘white supremacy,’ a plurality of white audiences will just shut down. I hope people will find a way to open up the conversation so they can hear these words without having a fear response, and be prepared to engage with these terms with the implicit understanding that they are not personally under attack.”

To Be Young, Gifted, and Black series calendar

Click here for details

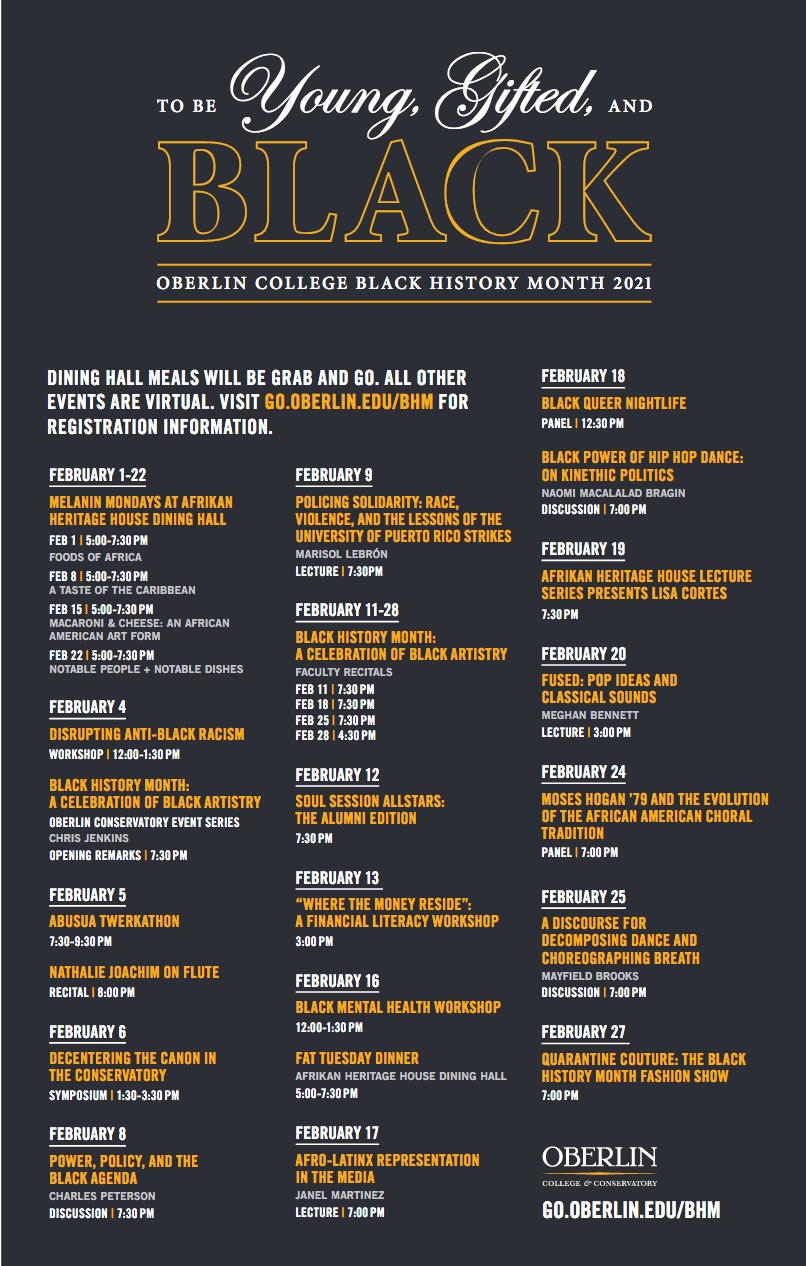

Saturday, February 6, at 1:30 pm — “Decentering the Canon in the Conservatory.” Naomi André, Loren Kajikawa, Imani Mosley, and Kira Thurman, discuss the historical marginalization of music that falls outside the lines of the traditionally defined canon. Moderated by Chris Jenkins, the symposium will include a Q&A period.

Thursday, February 11 at 7:30 pm — Violinists Sibbi Bernhardsson and David Bowlin join pianists Haewon Song and Robert Shannon in works by William Grant Still and Jeff Scott.

Thursday, February 18 at 7:30 pm — Katherine Jolly hosts a concert that includes works by Valerie Coleman, Allison Loggins-Hull, Maurice Arnold, Edmond Dédé, and William Grant Still. The evening features performances by Alexa Still (flute), Peter Slowik, Kirsten Docter, Troy Stephenson, and Marlea Simpson (violas), Drew Pattison (bassoon), James Howsmon (piano), and Christa Rakich (organ).

Thursday, February 25 at 7:30 pm — Jeff Scott hosts a concert that includes works by Abel Meeropol, Ulysses Kay, and Duke Ellington. The evening features performances by Jeff Scott (horn), Drew Pattison (bassoon), James Howsmon (piano), the Verona Quartet, and the Oberlin Orchestra, under the direction of Raphael Jiménez.

Sunday, February 28 at 4:30 pm — Francesca dePasquale and David Bowlin (violins), Darrett Adkins (cello), James Howsmon (piano), and Mark Edwards (harpsichord) perform music by William Grant Still, Dorothy Rudd Moore, Jeffrey Mumford, Joseph Bologne, and Chevalier de Saint-Georges.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com February 2, 2021.

Click here for a printable copy of this article