by Mike Telin

On Thursday, March 24 at 8:00 pm at Hall Auditorium, Oberlin Opera Theater will present Cimarosa’s two-act comic opera in a production directed by Jonathon Field, with Christopher Larkin conducting the Oberlin Orchestra. The opera will be sung in Italian with English supertitles. Performances run through Sunday. Tickets are available online.

Larkin has been a regular in the Hall Auditorium pit since 2007 when Field staged Mark Adamo’s Little Women, an opera for which he conducted the premiere in Houston.

On a recent sunny morning at a popular Oberlin coffee shop, I sat down with Jonathon Field and Christopher Larkin to talk about the opera and the production. This conversation was one of those where you simply turned on the recorder and the two longtime collaborators took it from there.

Christopher Larkin: I’ve always enjoyed coming here. Oberlin is an undergrad-only program — no grad students taking up the roles. I’ve had students who have done four major roles with me from freshman through senior year. Then they go to grad school with a huge advantage from having that experience. And it gives them an edge when they go into the world.

I also find it nice to work with younger people because things are less ingrained. You’re able to instill a certain work ethic — how well prepared they have to be when they show up to a rehearsal, otherwise they won’t make it. They’ll be fired in two days if they are not on top of it.

Mike Telin: What would you say to someone who asked, “Why should I come to this opera?”

CL: I always say you should come to see what these young people are capable of. Plus it’s live theater and we haven’t been able to do that for two years.

Jonathon Field: And this opera really is charming and very theatrical. Cimarosa knew what he was doing when it came to theater.

MT: I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t know a lot about Cimarosa.

CL: You’re not alone. His music is similar in style to Mozart, but because he didn’t write a lot of symphonic music, he didn’t get the same attention.

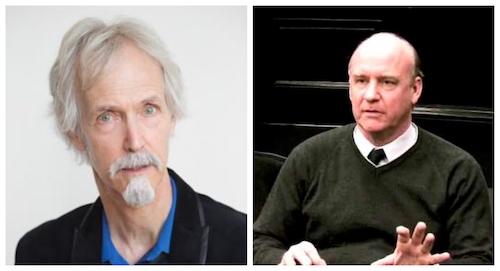

Left to right: Field, Larkin.

MT: Wasn’t this one of his most popular operas?

JF: Yes. When it first premiered in Austria, Emperor Leopold was so impressed that he had them repeat the entire thing from beginning to end.

C: They had dinner first and then came back and performed it again. But yes, it was very well received. It went to New York in—

JF: 1834.

CL: And the MET staged it in 1937. Some people say that Cimarosa wrote eighty-some operas — I think it’s more like 60, but yes, ll matrimonio was extremely popular in its day.

JF: I find with this piece that you can see where the traditions of Rossini and Donizetti come from. It’s got those theatrical traditions. One that I always get a kick out of is how the plot gets so heated that everything stops. Everybody becomes frozen wondering what is going on. Then there are these big ensembles that come out of that moment.

CL: Yes. In that way he’s very much like Mozart. Cimarosa’s ensembles are similar to Marriage of Figaro where they build and build in the number of characters, and the tempi keep getting faster and faster. The end of Act I is fun with Geronimo babbling nonsense sounds, because he can’t figure out what everyone is talking about.

It’s a fun piece and a great vehicle for the students. There’s a lot of secco recitative, which is difficult because there is so much fast Italian that has to be delivered freely. There’s also a very quick patter duet between the Count and Geronimo that begins Act II.

But I think it’s the recits that are the great learning tools because the singers have to know the language better, and the inflection of the language, to make it sound like a natural dialogue.

JF: You may have noticed that every year we do an opera in a foreign language. And doing the recitatives in a foreign language is even better for them.

MT: How about the plot?

JF: We talked about how popular it is as an opera, but as a play it was also very popular.

CL: The Clandestine Marriage.

JF: That’s right. It was immensely popular in England and then all over Europe. David Gerrick and George Colman the Elder wrote it in 1766. And that’s why so many of the characters’ names are British.

CL: How can you quickly condense the plot? Well, Paolino is the go-between for the two households. He used to be with the Count, but he sort of loaned him to Geronimo’s house — so Paolino knows both men. And when he moves to Geronimo’s house he falls in love with Carolina, the younger daughter, and they are secretly married. In other words, when the opera starts they have already been sleeping together for three months.

JF: One of the things I read when studying the plot is that women were not allowed to legally marry without the consent of their father until 1820.

CL: Paolino comes up with this great idea — he knows the Count wants to get married and Geronimo is offering this big dowry. So he says, I’ll get the Count to marry Elisetta, and Geronimo will be happy because he will now be married into royalty. And the Count will be happy because of the big dowry. Hilarity ensues.

MT: I understand the production is set in “semi-period.”

JF: We’re setting it in 1810 and the reason is pragmatic. The opera begins with a duet between Carolina and Paolino saying how in love they are with each other. So I’m starting them in bed — we see the covers move and they pop up and of course need to get dressed.

If I dressed them prior to 1790 there’d be hoops and corsets. And if I dressed after 1820 — again there’s more clothes to put on. So there’s a window of time from about 1805 until 1820 when clothes come on and off easily. So I’ve got enough time to get them dressed onstage, and yet it is in that time period when women still needed to get permission from their fathers to marry.

CL: So it’s completely self-serving.

JF: Absolutely self-serving.

MT: That opening duet is beautiful but quite long.

CL: Yes it is. And they both sing a high C in it, but it goes by so quickly that you barely notice it — it has to be part of the line.

But most of the arias aren’t show-pieces. They’re more about character than about vocal fireworks. And like Mozart, there are moments that are genuinely serious, which helps to set off the comic relief so well.

JF: But of all the characters, Paolino and Carolina are the only normal ones. The rest are just a little nutty. And they are the only couple who are in it for each other.

Top photo by Jonathan Clark.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 18, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article