by Mike Telin

On Friday, May 17 at 7:30 pm in Reinberger Chamber Music Hall at Severance Music Center, Tao will present “Power and Influence.” The program features music by Sergei Rachmaninoff, Billy Strayhorn, Stephen Sondheim, Robert Schumann, and Buddy Kaye. Capping off the evening, Cleveland Orchestra cellist Dane Johansen will join Tao in Rachmaninoff’s Cello Sonata. The recital is part of the Orchestra’s Mandel Opera & Humanities Festival. Tickets are available online. Click here to see the full Festival schedule.

I caught up with the pianist on Zoom and began our conversation by asking him about the inspiration behind his fascinating program.

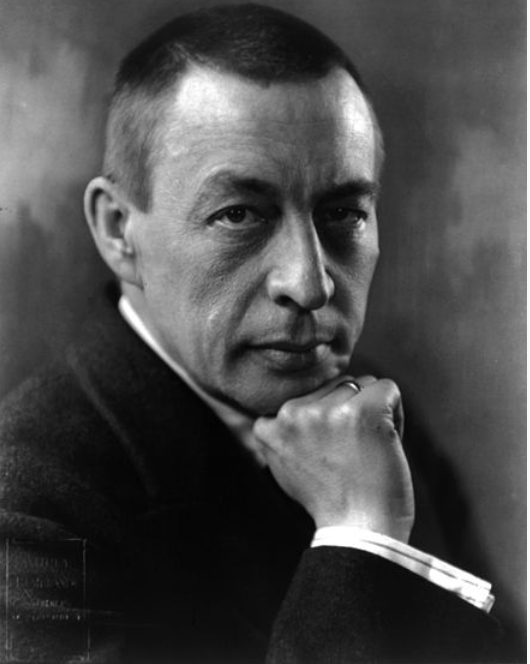

Conrad Tao: Like a lot of things for me, it was timing in a way. I was approached by a presenter in California about doing a Rachmaninoff program to celebrate his 150th birthday. The truth is that doing a Rachmaninoff program wasn’t on my radar even though I love playing the piano concertos and have played some of the preludes.

But it just so happened that when the presenter called, I had recently seen the 1945 romantic drama Brief Encounter, which is written by Noel Coward and directed by David Lean. It’s one of the most romantic movies I’ve ever seen. It’s rich and full of subtext. And the only music that is used is Rach 2, and the way that it’s used is really lovely and fascinating.

Since I had recently seen this movie, I was open to the way Rachmaninoff’s music inspires and can inspire. Which got me thinking — if you’re going to use Rach 2 you’ve got to use the second movement. And not only the second movement, but the second theme of the third movement.

Mike Telin: A Clevelander, and his aunt played viola in The Cleveland Orchestra.

CT: I didn’t know that. I’ll remember that and make a note of it when I speak to the audience.

And because of those songs I saw no reason to shy away from the fact that Rachmaninoff was this supremely gifted melody writer, and it’s not surprising that these melodies have been used in popular song.

As I thought about that, I thought about how little we know about Rachmaninoff’s time in New York. We know that he went to jazz clubs. We know that he heard Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. We know that he heard Art Tatum perform, and we know that he was a fan.

He didn’t write a ton of music after he moved to New York, but what he did compose was quite substantial — the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Paganini Rhapsody, and the Symphonic Dances. In the case of, say, the Fourth Concerto and the Paganini Rhapsody, you can hear the influence of jazz on his own writing, his own harmonic language.

I think the Fourth Concerto is a piece where you can hear him trying new approaches to harmonic development, and his fascination with how much you can accomplish with just the chromatic scale. And in the Paganini Rhapsody he refines these methods — you have something like the fifteenth variation, which I think sounds like it could be a Tatum improvisation.

So that was the initial catalyst that got me thinking about Rachmaninoff and his relation to American songwriting — he’s moving to New York at the time when the Great American Songbook and Tin Pan Alley are really happening. It also got me thinking about his influence on composers and songwriters who came after him.

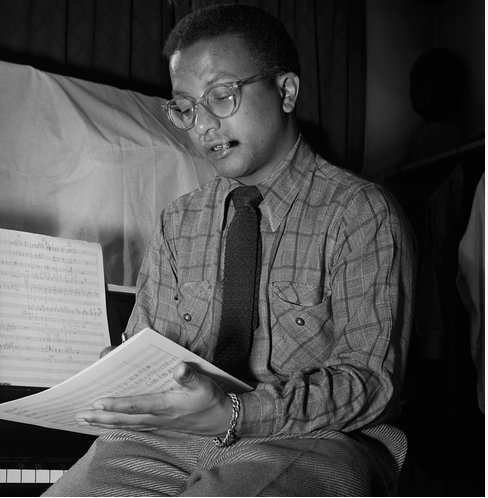

MT: How do the Billy Strayhorn pieces fit in?

MT: And then there’s Harold Arlen’s Over the Rainbow.

CT: At the end of the day, most of my programs are both concepts and collections of music that I think are beautiful and sound good together. And the Over the Rainbow transcription is just something that I did on my own time that fits into the program so perfectly. It also happens to be in the same key as Lush Life and the same key as the eighteenth variation of the Rach/Pag.

And to draw even more links, the fifteenth variation happens to be the first music I remember improvising on. I would just improvise these crazy intros to it, which was a pivotal experience for me as a teenager.

MT: Is there a message that you’re trying to send to the audience? You don’t have to have one — I’m just curious to know if there is one.

CT: It’s a good question. I guess the hope is to simply draw attention to the concept of Rachmaninoff as a proto-pop composer. And as I said, there is zero shame in that because it’s such a great gift.

I read an interview with Sondheim, and he said that sometimes the classical hoity-toity dismiss Rachmaninoff because he’s too accessible or something along those lines. And I think there’s a grain of truth to what Sondheim is saying.

MT: This has been a fascinating conversation. Is there anything else you’d like to share?

CT: Other than the fact that I’m so happy to close the program with the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata with Dane Johansen. It’s one of the earliest pieces I played as a pianist. And it has a glorious third movement that, to my knowledge, has yet to be pilfered for a pop song. But it’s not too late.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 15, 2024

Click here for a printable copy of this article