by Daniel Hathaway

Scott Metcalfe will bring 14 singers from his Blue Heron Renaissance Choir in Boston to the Helen D. Schubert Concert Series at St. John’s Cathedral in downtown Cleveland on Friday evening, April 11 at 7:30 pm to sing music associated with Canterbury Cathedral in the last decade before the English Reformation.

The program will include an elaborate plainchant Kyrie (Deus creator omnium), a five-part mass by Robert Jones (Missa Spes nostra), and a votive antiphon by Robert Hunt (Stabat mater). “I’m quite sure that none of these pieces have ever been sung in Cleveland before,” Metcalfe said in a recent phone conversation.

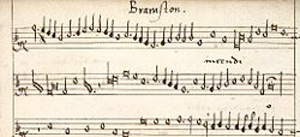

The repertory is taken from the Peterhouse partbooks, a set of manuscript scores each containing music for a single voice part, which were probably copied around 1540 at Magdalen College, Oxford, for use at Canterbury Cathedral and now held at Peterhouse at Cambridge University.

They help fill in our knowledge of what was being sung in important English choral establishments between Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries (1536-1541) and the Protestant movement that led to huge changes in musical styles by the end of that decade — after the Church of England cut its ties to Rome.

It’s something of a miracle that the Canterbury partbooks survived. “A huge amount of early 16th century church music was lost,” Metcalfe said. “When the Protestants were in charge for six years during the reign of Edward VI, Catholic music got stashed away, then suddenly it reappeared. After the Elizabethan ‘settlement,’ the music was no longer useable because nobody was singing long festival masses or votive antiphons to Mary, at least in public.”

The partbooks came to Peterhouse in the 1630s, having been collected by the master of the college chapel, John Cousins, and by that point were only partially intact — the tenor book is missing from each of the three sets. Reconstructing those missing fifth voice parts has been a thirty-year mission by now-retired University of Exeter musicologist Nick Sandon. “Nick has recomposed the tenor for all 50 of the unique pieces,” Metcalfe said. “He has an amazing gift.”

Metcalfe describes Jones’s mass as “a wonderful piece, beautifully crafted, with lovely melodies and harmonies. We know very little about the composer, but it’s obvious from this mass that it’s not the only large-scale piece that he wrote.”

“Richard Hunt is even more obscure. His Stabat mater is not as polished as other settings, but its rough expression is really appropriate — gutsy and with a sense of drama. It’s about fifteen minutes long and in the second half he ratchets up the intensity during a turba or crowd scene. Some of our audiences have reacted very strongly to it. It’s meant to be heart-wrenching.”

English masses never set the Kyrie eleison polyphonically, thus Blue Heron will precede Jones’s Gloria in excelsis with the plainchant Kyrie Deus creator omnium, a festival version “troped” or larded with extra text. “It’s a lovely piece of music as well, and it’s nice to hear the contrast between polyphony and a choir’s ordinary diet of plainsong.”

After Friday evening’s Blue Heron concert, Scott Metcalfe will take profit of an open day in his schedule and time travel ahead two centuries to play baroque violin in a Saturday afternoon benefit with Les Délices. On Sunday, it’s back to the 1540s as he takes Blue Heron to The Cloisters in New York for two performances of the Canterbury program.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 8, 2014

Click here for a printable version of this article.