by Mike Telin

If you’ve never really gotten into the music of Béla Bartók, the Takács Quartet’s two-evening cycle of his six string quartets on March 17 and 18 on the Cleveland Chamber Music Society series at Plymouth Church is an excellent opportunity to immerse yourself in his musical language.

In Part One of this series of articles, we spoke with Peter Laki about Bartók’s creative use of elements derived from folk music in writing his quartets. Laki went on to note that “the third quartet, which is very abstract, is filled with these tiny motives that he never would have come up with had he not been steeped in folk music.

“In the fourth quartet there is a creative reworking of a certain type of Romanian song that he found because he went beyond the Hungarian traditions and explored the music of a lot of other groups in the region that he worked with and arranged, isolating particular elements and working with them in inventive ways.”

In order to further explore this aspect of Bartók’s music, we asked Oberlin Conservatory’s Barker Professor of Music Theory, Brian Alegant, how he goes about explaining all of this to his students.

“With Bartók, it’s music that you can approach in many different ways depending on your level of experience. I’ve been listening to them almost as long as I’ve been walking this earth,” Alegant told us by phone.

He starts with an overview — Bartók from 10,000 feet — then zeroes in for a series of closer, more detailed observations.

“When I teach the quartets, I always begin with large-scale form and cool spots. What’s the form, and what are the places that make you think, Wow! that’s really interesting? There are romantic gestures and folk elements in there but the language is very different. I think the easiest way to listen to his music is just to ask how the music is coming at you in terms of color and energy. That’s an easy thing for people to get into without having to go too much below the surface.”

Going deeper into the music, Alegant moves on to point out its structural details to his students. “I’ll get into what a cadence is and what the harmonic pillars are. I’ll talk a lot about thematic development, almost like I do with Beethoven. As you get further into it you can trace motives and see what he is doing polyphonically and you can look at them the same way as you can look at the late, a minor Beethoven quartet. I think the motivic cells are really audible. Then you can listen for symmetrical inversion — where Bartók turns themes upside down and replays them backwards.”

What kind of motives does Bartók use? “If you pick at the music a little more you can see there are chromatic cells, diatonic cells, and whole-tone cells. The language on the surface meshes together these cells and colors.”

If that’s beginning to sound a bit too analytical, Alegant is quick to point out that this kind of closer observation helps one appreciate Bartók’s art. “Part of my job is to make it musical to the students,” he said. “For example, in Bartók’s fourth quartet I will label three intervallic cells. One is chromatic or a chromatic cluster with no gaps – I call that X. If you widen those a little bit you get b-flat –c-d and e and that’s a whole-tone chunk — I call that Y. Another combination he uses is C and c-sharp & f-sharp and G — two tri-tones and a minor second. I call that Z. These three cells permeate almost every aspect of the movement.”

Stay with us — the plot is beginning to thicken. Alegant continues, “Those cells determine the canonic entries of each instrument. Bartók takes each cell and has each entrance go up by a half step or up by whole steps.

“What happens eventually is that all the cells get spread out throughout the register. At first, they’re these black dots like gnats on your windshield when you drive, but gradually they become several octaves wide.

“There are a couple of places where Bartók uses glissandos to color in the gap between these three pitch class cells. The coolest thing is that we can train students to hear this, and when they do, they say, OK, I get it!

Tomorrow, in Part Three, we’ll hear more from Peter Laki and gather impressions about Bartók’s quartets from Cavani Quartet violinist Annie Fullard and music critic Donald Rosenberg.

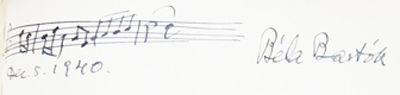

Bartók’s 1940 autograph book entry courtesy of the Cleveland Orchestra archives.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 14, 2014

Click here for a printable version of this article.