by Mike Telin

While scientifically this phenomenon is known as the acoustic, “more importantly it’s the concept of having the space become the nth member of the ensemble,” artistic director Jay White said during a recent telephone conversation. =

On Friday, May 13 at 7:30 pm in the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, White will lead Quire Cleveland in “Resonant Glory: Music for Grand Spaces.” The program, which celebrates the union of music and architecture, will be repeated on Saturday at 8:00 pm at St. Noel Church in Willoughby, and on Sunday at 5:00 pm at St. Sebastian Church in Akron. The concerts are free.

White said that his inspiration for the program came while he was making a list of his favorite pieces for double choir. “I thought, wait a minute, why do we have double choir works to begin with?” Answering that question led White to alter his approach to making the list.

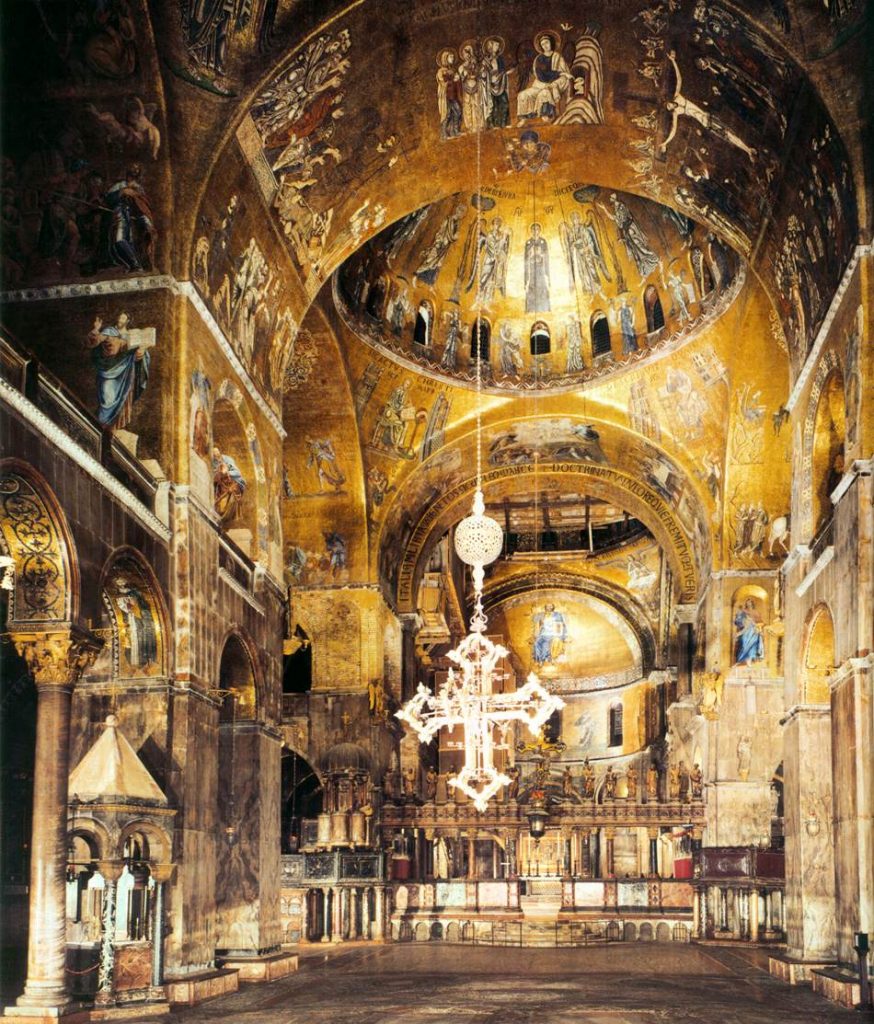

“I started looking at the spaces first,” he said. “Then I searched for Renaissance composers at St. Mark’s Basilica and came up with a handful of names. I did the same thing for Notre Dame and so on.”

San Marco Venice

The program includes works by Brumel (Notre-Dame, Paris), Lassus (Allerheiligen-Hofkirche, Munich), Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli (Basilica di San Marco,Venice), Victoria (Basilica di Sant’Apollinare, Rome), Lienas (Convento del Carmen, Mexico City), J.S. Bach (Thomaskirche, Leipzig), Stanford (Trinity College Chapel, Cambridge), and Vaughan Williams (Westminster Cathedral, London).

While many of the pieces were written specifically for the spaces that are highlighted in the program, in all probability they were sung in those spaces at some point. “I did discover that the Victoria was most likely written for a different Cathedral. However, he was also employed in Rome at Sant’Apollinare. So I’m making the assumption that this piece was also sung there. And why not — it’s a Salve Regina.”

How many places were under consideration? “I started with the most well-knowns in my head, which of course were St. Mark’s, Westminster Cathedral, and Notre-Dame. And while the Thomaskirche is not nearly as big as Notre-Dame, it is still a grand space to me simply because of its relationship to Bach.”

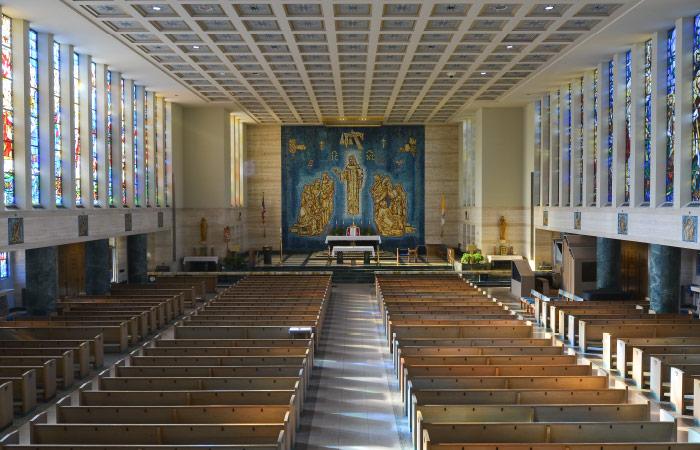

Westminster Cathedral London

As far as the number of pieces, White began with fifteen to twenty. “I had to whittle that down, and concentrated mostly on eight- to twelve-voice pieces, whether they were in double or triple choir, or some form of that.”

A work’s length was also a consideration. “Stanford’s Magnificat for Double Choir clocks in at nine to ten minutes, so it is a lengthier piece, but I wanted the audience to experience what it’s like to become engulfed in sound for a longer period of time.”

The program begins with the “Kyrie” from Antoine Brumel’s Missa ‘Et ecce terrae motus’ (EarthQuake Mass), an eight-minute piece that White said is “literally a wash of sound,” and full of intricacies. “In that period, and even into the 19th century, the choir’s music was really not a showpiece, it was an opportunity for the words of the service to be heard in a different fashion.”

White noted that while the choir and the clergy were located in one part of the Cathedral, the congregants were out in the nave. “It is interesting to think of a piece with 16th notes speeding along. While you’re not going to hear any distinction if you’re 40-50 feet away, more importantly is the overall sound that the space is giving us based on what the composer has chosen to do?”

White also noted that as time went on the role of the choir became more than just an element in the service. “That’s when we get to works like Bach’s Komm, Jesu, komm, and Vaughan Williams’ Mass in g minor, because by that point we have a different understanding of the purpose of voices in consort.”

Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist Cleveland

How does White think the pieces will sound in the spaces where Quire will be performing? “I think the earlier ones are going to sound more like what they were intended to sound like in a space like the Cathedral of Saint John, which is what I consider to be a typical Gothic church. I call St. Sebastian a shoebox church because

it is a rectangle,” he said. “It has a beautiful acoustic that is fairly clear from the altar through maybe the midpoint of the sanctuary. So I would say that the later pieces will work for those who are in the front part of the church, but then again, the earlier pieces are going to sound wonderful no matter where you are. And St. Noel is a modern structure so I can, with most confidence, say that the later pieces from Lienas’ Credidi on, are going to sound a little more clear than the others.”

St. Sebastian Parish Akron

White added that the challenge in all three spaces is going to be figuring out the positioning of the ensemble. “How much, if any separation can we have depending on what the space is going to give back to us.”

Although White began planning this program pre-COVID, he has been looking forward to introducing it to the public for some time. “Especially interesting to me are the Stanford and Vaughan Williams,” he said. “I have not had the pleasure of singing those pieces and I wanted to give the choir the opportunity to sing with a different sonority in their heads — something away from the Renaissance period, to allow them to use their instrument in a different way. And with a program that progresses from music that was written quite early all the way to the mid-20th century, the audience will get to experience a smorgasbord of what these sonorities are, and how they have developed over the course of time.”

Is there a piece White can’t wait to rehearse and perform? “There is one, Victoria’s Salve Regina,” he said. “And every time I’m going through it, it catches me. There’s just something about the way that he wrote that elicits a visceral response in me. So that is definitely one that I really feel a connection to.”

When it comes to complexity, White noted that while the “Earthquake Mass” is wonderful, it will require some woodshedding. “On the opposite end of the spectrum are the Stanford and Vaughan Williams — when you hear one of his pieces you know it’s Vaughan Williams, so we need to make sure that happens.”

Out of curiosity I ask White if choral works are still being written for specific spaces as much as they were in the past. “That’s a good question. As much as I would love to believe that to be true, having a composer who is also your choirmaster and or organist, is not something I have experienced much recently. I think the last time I had an experience like that was at the National Cathedral in D.C. where we did have either emeritus organ masters, or choirmasters, or organists who were also composers, who were writing for the choir in that space.”

Winding down our conversation, White said that after COVID he is aware that people who are attending choral concerts are hearing the music in an entirely new way. “Their appreciation for the vast diversity that we have within our choral music scene in Cleveland is at a much greater level than I think I have ever experienced.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 11, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article