by Robert Rollin

Tamino, a foreign prince tries to fight a menacing dragon, but faints after loosing all his arrows. Three ladies appear and save him by killing the dragon with their spears. They praise their own success and each, interested in Tamino, tries to send the others back to their mistress. Tamino awakens and hides when Papageno enters from above, introducing himself as the Queen of the Night’s bird catcher in a lively aria. He claims he strangled the dragon with his bare hands and the Ladies punish his lie by padlocking his mouth. They hand Tamino a medallion with Pamina’s picture. She is the Queen’s daughter. Tamino immediately falls in love with her image.

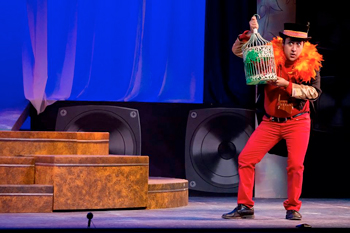

Tenor Brian Skoog enlivened the role of Tamino with a lovely vocal quality and a strong voice that consistently sailed above the thickest orchestral accompaniment. Baritone Armando Contreras acted skillfully as Papageno, constantly clutching his pan flute, but his voice frequently disappeared beneath the accompanying orchestral texture. He had a good vocal quality, but needed to project better.

Soprano Zoë Schumann, as the Queen of the Night, sparkled in her acrobatic arias, tossing off difficult high passages with ease. She also clearly enunciated her part, keeping her words constantly intelligible. The early quintet with the Queen of the Night, Tamino, and the three ladies was gorgeous. The ladies gave Tamino his magic flute, and Papageno, his bells.

Tenor Tristan G. Montague, as Monostatos, also acted well, but his voice sometimes struggled to be heard. In contrast, bass I Sheng Huang, as Sarastro, had a terrific dark quality that projected very well and gave the role the requisite dignity and poise. Ensembles were excellent, especially the nonet later in Act I. The well-rehearsed choruses were also very good.

The sensitive Act II Prelude reminded the audience of just how beautifully the orchestra played throughout. Sarastro entered and placed Tamino and Papageno on trial. His strophic aria, “There’s No Revenge Here,” was outstanding.

Soprano Caroline Bergan sang Pamina skillfully and tastefully. Though nowhere near as challenging and wide-ranging as the Queen of the Night, the youthful role nevertheless had some very virtuosic passages. The aria lamenting her expected loss of Tamino, “Peace Will Come in Death Alone,” reached the depths of pathos.

“How better to Part,” the trio with Sarastro, Pamina, and Tamino was especially effective, as were all the Act II ensembles and choruses. The beautiful use of the “bells” and the scenes between Papageno and Papagena acted as foils to all the austere veiled Masonic references. The patter duet was delightful as always.

The supporting roles were consistently excellent, and conductor Harry Davidson pushed the pace where needed. David Bamberger’s direction made the best of the hall’s limitations and also kept the production moving.

Photo by Leigh-Anne Dennison.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 12, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.