by Daniel Hathaway

On Saturday afternoon, August 23, CIPC organized a reunion of its four top winners from 2013, one year and two weeks after the final round when they played concertos in Severance Hall with The Cleveland Orchestra. Last year they faced off as competitors, but on Sunday in Gartner Auditorium at the Cleveland Museum of Art, they paired up collaboratively to play J.S. Bach double keyboard concertos with Apollo’s Fire and, in the second half of the 4:00 pm concert, swapped partners to play two-piano works by Mozart, Milhaud and Rachmaninoff. A gala dinner for patrons followed the performance in the museum’s Atrium.

It was probably a logistical nightmare to bring four globe-trotting pianists to Cleveland for such an event, and rehearsal time was surely limited. Add to that the reality that all four are solo pianists who infrequently play multiple-hand repertory and not with each other, and you’re probably going to end up with performances that are stronger in the categories of Fun and Good Will than Memorable Musical Experiences. So be it. That takes nothing away from an afternoon full of joyful musical camaraderie that provided the perfect prelude to a benefit dinner.

Stanislav Khristenko and Jiyan Sun led off with Bach’s C-Major concerto, BWV 1061, a piece which began life as a work for two harpsichords alone — string parts were added later, but only sparsely and maybe not by the composer. Khristenko and Sun played with fine clarity of touch and transparency of tone, though Sun was prone to nudging the tempo ahead in antiphonal sections.

Arseny Tarasevich-Nikolaev and François Dumont took the stage next for the c-minor concerto, BWV 1062, which Bach arranged from the better-known double violin concerto. Thicker in both keyboard and orchestral textures, the c-minor piece doesn’t work quite as well as its C-Major sister on modern pianos, but conductor Jeannette Sorrell and the two keyboardists delivered a robust and spirited performance with fine nuances in the slow movement.

The pairing of pianos with period instruments — rather than the more common practice of joining modern pianos with modern instruments — makes for strange stagefellows, but Tarasevich-Nikolaev, Dumont, Sorrell and the 12 members of Apollo’s Fire arrived at agreeable compromises and met each other on common ground. A few tuning problems and some discomfort in the audience had a common source: the air conditioning in Gartner was on overdrive on Saturday.

After intermission, the Steinways were rearranged head to tail for two-piano music. Dumont and Sun began the second half with a big, carefree reading of the first movement of Mozart’s D-Major sonata, followed by a thoroughly extroverted performance of Milhaud’s Scaramouche, with its bold and brassy final Brazileira.

Khristenko and Tarasevich-Nikolaev responded with Rachmaninoff’s mostly-poetic Suite No. 1, plumbing its depths of sentiment and decorating the first three movements (Barcarolle, Night…Love and Tears), with exquisite filigree. Then they drew on their mutual virtuosity to evoke the joyful jangle of Russian bells in Easter.

What to end with but a piece involving all four pianists, and what to choose but the Galop-Marche for eight hands on one keyboard by August Lavignac (1889-1972), a professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatory who taught Henri Cassadesus, whose nephew, Robert, founded what is now the Cleveland International Piano Competition.

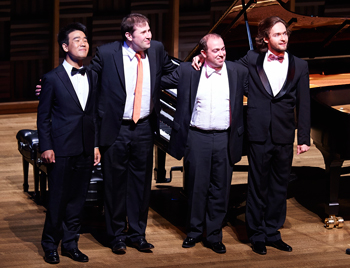

After inspiring chuckles by moving four benches to the left-hand piano, turning them sideways and jockeying for position, Stanislav Khristenko, Jiayan Sun, Arseny Tarasevich-Nikolaev and François Dumont treated the capacity audience to a hysterical romp through a work you may never hear again in public (though you might at a party of well-lubricated pianists). Just as there had been no mention in the program of what prizes each of the four laureates had won a year ago, this concert ended in a burst of congeniality and friendship that other piano competitions should envy.

Speaking of congeniality, when the beginning of the concert was delayed due to a construction bottleneck that clogged the entrance to the parking garage, Apollo’s Fire cellist René Schiffer offered to treat the crowd to an unplanned prelude. The Allemande from a Bach unaccompanied suite made the wait a pleasure.

Photos by Roger Mastroianni.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com August 26, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article.