by Guytano Parks

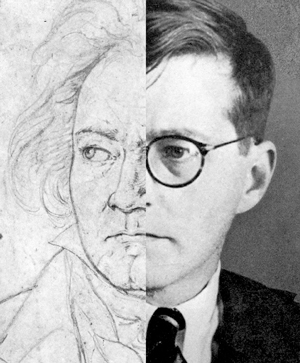

Included in the Festival were films screened at The Cleveland Institute of Art (A Clockwork Orange) and The Cleveland Museum of Art (The New Babylon, featuring Shostakovich’s first film score), in addition to pre-film and pre-concert talks and a chamber music performance by members of The Cleveland Orchestra. On Saturday afternoon as a related event, the Metropolitan Opera’s production of The Nose by Shostakovich was shown LIVE in HD in select Northeast Ohio movie theaters.

Described by Robert Schumann as a “slender Greek maiden” compared to the Third and Fifth symphonies, Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony in B-flat is considerably less forceful and dramatic. Beginning with a slow overture-like introduction, much like that of the symphonies of Haydn and a few of Mozart’s, a sense of foreshadowing and anticipation was felt as Welser-Möst led the players into the ensuing Allegro vivace section. The playing was exuberant, teeming with clean and precise attacks with phrases that swelled and blossomed. Breathtaking pianissimos contrasted with the energized beats of the timpani and the exciting playing of the brass.

The second movement Adagio — one of Beethoven’s greatest — opened with lovely hushed playing by the violins echoed by the woodwinds. Berlioz likened this slow movement to the story of Francesca da Rimini in Dante’s Divine Comedy, so moving that it reduced Virgil to tears and caused Dante to fall “like a dead body.”

Sharp syncopations, arresting sforzandos and back-and-forth play between ascending and descending diminished-seventh arpeggios were delivered with skill and wit, giving the third movement Menuetto lots of character. The Allegro ma non troppo finale was light and spry, notable for crisply clipped phrases, crystal-clear articulation and more breathtaking pianissimo playing.

After intermission came Shostakovich’s sprawling, hour-long, five movement Symphony No. 8 in c minor, written in little more than two months’ time. In 1943 it was deemed a pessimistic work, full of “unhealthy individualism” and “not recommended” for performance. It was banned as it laments the millions killed or mutilated by the war.

The expansive Adagio — Allegro non troppo first movement includes phrases made up of painfully expressive intervals, with an ambiguous harmonic base making for an uneasy and unsettled feeling. Welser-Möst led the orchestra through an extremely slow-moving kaleidoscope of color and texture in this bleak and ever-changing landscape of sound with a sense of despair as well as wonderment. The repeated drum rolls crescendoing into explosive, full orchestral screams were positively unnerving. Dotted rhythms and insistent brass playing urged the music forward at times when there were moments of optimism and hope. The English horn solo near the end was beautiful as the violins hovered above in a sustained, pianissimo tremolo before a trumpet fanfare heralded the concluding peaceful resolution.

A sense of the burlesque, strident and sardonic, prevailed throughout the second movement Allegretto as the piccolo took the lead before the lively and energetic third movement Allegro non troppo was set into motion. The violas tossed their incessant rhythmic figures back-and-forth athletically between sections, echoed and repeated in a tour du force of perpetual motion. Humor and wit also abounded as all forces joined in this menacing and driven music.

The ten-measure passacaglia theme of the fourth movement Largo was serious and intense. Its many, lugubrious repetitions included notable solos horn, piccolo, flutter-tonguing flutes and clarinet. The final movement Allegretto commenced practically unnoticed as a considerably lighter mood was established, but the sense of tension remained and a repeat of the first movement’s screaming outburst occurred. The poignant bass clarinet solo at the end brought this massive and turbulent c minor work to its peaceful and sublime resolution in C major.

Welser-Möst acknowledged the many outstanding soloists and sections with individual bows during the prolonged and enthusiastic ovation.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 29, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.