by Robert Rollin

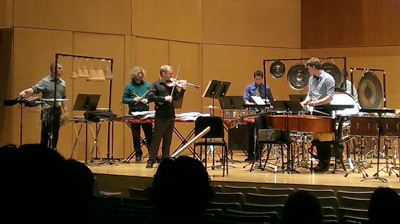

According to its mission statement, Clocks in Motion, is “dedicated to performing modern chamber music and commissioning new repertoire.” The ensemble’s membership ranges from undergraduate and graduate students to those with the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in percussion. At the concert all the performers evidenced a remarkable professionalism, skillful performance, and prompt, careful organization and structuring of the complex percussion resources.

The evening’s highlight was Lou Harrison’s Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra (1940-1959) with guest soloist Evan Kleve. Already in the rapid first movement, Allegro maestoso, Kleve evidenced great preparation and virtuosity as he tossed off difficult passagework replete with mixed metrical groupings. The accompanying percussion parts included mallet percussion, membranephones, metalliphones, and wooden instruments judiciously laid out around each of the five percussionists. Given the percussion instruments’ potential dynamic power, the balance between soloist and ensemble was nothing short of remarkable.

The second movement, Largo; cantabile, was more lyrical, delicate, and expressive, as greater reliance was placed upon the strange setup of a string bass on its back being hit with percussion mallets to create a gamelan-like effect. Harrison is noted for his interest in Far Eastern music, and this connection was clearly present in the piece. The third movement, Allegro, vigoroso, poco presto, was again fast and excited. Even more asymmetrical groupings took place here, with the added technique of intricate cross rhythms. Violinist Kleve was excellent throughout and the balance of accompaniment was consistently fine.

In addition to the concert, the group had spent an afternoon looking at Cleveland State student composers’ works. Though not listed on the program, the group selected student Buck McDaniel’s Different Parts for a same day concert performance. The two-movement piece used three percussion parts and piano in a colorful mélange featuring mallet percussion, tenor drums, wood blocks, snare drums, gongs, and other non-pitched instruments.

Herbert Brün’s At Loose Ends: (1974) for piano and three percussionists was a single movement piece employing diverse coloristic resources. Pianist Jennifer Hedstrom’s part was itself diverse. Several times she changed off to celesta, adding a soft ringing timbre. She also strummed the piano strings in an extended inner piano passage, and hammered the chimes in a sizable passage. Marimbas and non-pitched percussion dominated the accompaniment. At one point interesting spatial effects took place as each percussionist played snare drum rolls in a conversation with the others. A similar technique focused on simultaneous marimba rolls in each mallet part. Other timbral diversities included use of a large rack of temple blocks, several flexitons, and extended use of woodblocks and high-pitched log drums.

Hedstrom started the concert with a fine performance of John Cage’s Bacchanale (1940) for prepared piano. This was largely a perpetual motion piece. The second section periodically slowed to quasi cadences. Like Harrison’s special use of the string bass in his Violin Concerto with Percussion Orchestra (1940), Cage demanded a prepared set up in which several gamelan-sounding sonorities take place. This gave the piece an Eastern cast.

The concert’s entire second half contained experimental composer Iannis Xenakis’ fort-five minute Pléïades (1979) in four movements. Xenakis is known for using the computer and information theory to help generate his music. The piece employed six performers. Any order of movements is allowed, as long as Mélanges is played first or last. The performers wore headphones with click tracks to help maintain tempo and ensemble. Claviers, or Keyboards, the first movement, employed only mallet percussion for a rapidly flowing bright piece. Very fast-moving unison passages among the five players created a remarkable color and musical flow. The precision was truly amazing.

Métaux, or Metaliphones, the second movement, used six specially created glockenspiel-like instruments. Xenakis himself specified the need for these instruments, but never got involved in their creation. He also requested that pitch distances between adjacent metal bars never be closer than three-quarters of a tone. This produced an intense sonorous kinship to the metal gamelan instruments native to Southeast Asia. The piece ranged from piercingly loud fortissimos to intriguing diminuendos to pianissimo. The fortissimo passages’ dominance made the movement difficult to endure. One might say the composer missed several good chances to quit. Notwithstanding, the performance was meticulous.

Various drums dominated Peaux, or Membraniphones. Bongos, tenor drums, timbales, bass drums, timpani, and more, were used exclusively here. Again the movement seemed a bit too long, and again use of periodic diminuendos was a mitigating factor.

Mélanges, as the title implies, intermingled all features of the preceding movements. This made for a lively conclusion to a piece that dragged in the middle.

Clocks in Motion played with uncanny precision all evening.

Photo by Guytano Parks.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 27, 2013

Click here for a printable version of this article.