by Timothy Robson

The concert, titled “Boulez the Modernist I” and organized by CIM head of composition Keith Fitch, took place in the school’s Mixon Hall to an almost sell-out audience. The performers included members of The Cleveland Orchestra as well as guest artists.

The concept of modernism in music is somewhat slippery. In his 2010 book Boulez, Music, and Philosophy, Edward Campbell defines modernism as “the conviction that music is not a static phenomenon defined by timeless truths and classical principles, but rather something which is intrinsically historical and developmental.” Although all of the works on this program fit Campbell’s broad definition of modernism, only a few occupied the severely dissonant brand of modernism espoused in Boulez’s own works.

Elliott Carter’s Woodwind Quintet dates from the decade after he studied in Paris with noted musical pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. Its two movements are neoclassical in style, without the rhythmic complexity and atonality of his works after 1950. The second movement is especially inventive — jazzy, influenced by Hindemith, and sporting a French sensibility. Solo passages blend in and out of a complicated polyphonic texture. The performers, Mary Kay Fink, flute, Terry Orcutt, oboe, Robert Woolfrey, clarinet, Barrick Stees, bassoon, and Richard King, horn, served as the anchors of this concert, as an ensemble and as solo performers. Their performance was precise, well-articulated, and blended in sound.

Throughout his career, Luciano Berio produced a series of numbered “sequences” for famous instrumental players (and one for his then-wife, mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian). The purpose of these works was to exploit the outer extremes of the instruments’ capabilities. Cleveland Orchestra principal oboe Frank Rosenwein played the fearsomely virtuosic Sequenza VII for solo oboe. The work is centered around the note “b” which is heard from backstage as a very soft electronic drone. The concept of melody is left far behind. The music is nervous and constantly in motion, with extremes of ornamentation, pitch, and dynamics. Rosenwein’s performance was peerless musically and theatrically. He was called upon to create multiphonics, bend pitches, and flutter tongue, all at breakneck speed. In an afternoon of fine performances, this one was astonishing.

György Ligeti’s Six Bagatelles for Wind Quintet derives from his earlier set of eleven short movements for solo piano, Musica Ricercata. Ligeti limits himself to a set of pitches, adding to that set in each succeeding movement, thus enriching the harmonic palette as the work progresses. The movements are mostly tonal and influenced by Hungarian folk music in their use of rhythmic ostinatos and harmonies. The concert’s most notable moment of sheer beauty was the third bagatelle (Allegro grazioso), in which a soft, descending, seven-note pattern is repeated incessantly below a serenely tonal melody. The Carter Quintet performers also played the Ligeti Bagatelles. They made easy work of the piece’s musical complexity.

Robert Woolfrey played the solo version of Boulez’s Domaines pour clarinette, a work which leaves several elements to the discretion of the performer. Beginning stage left, Woolfrey moved among six music stands at various locations on the stage, playing a section of the score at each — in the order that he chose. At the last stand he played the 6th section of music, then proceeded in retrograde, moving back across the stage. Woolfrey’s playing was convincing, though unlike much of Boulez’s later music, the concept of the piece was more interesting than the actual music.

Mary Kay Fink performed PICCOLO, an excerpt from Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Der Jahreslauf, itself a part of Licht, Stockhausen’s monumental 29-hour cycle of operas. She performed the solo piccolo version authorized by the composer, from the balcony overlooking the stage, in a ray of sunlight coming through the windows of Mixon Hall. Stockhausen calls for the performer to be in a spotlight, so this lighting effect was serendipitous. Her performance was haunting, her piccolo tone chameleon-like, sometimes even sounding like an oboe. The brief work was a highlight of the afternoon.

Maurice Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite, in Mark Popkin’s arrangement for woodwind sextet, added English hornist Devin Hinzo to the mix. The music was like meeting an old friend after two hours of strangers. Ravel’s suite featured frequently on Boulez’s orchestral programs, and although Popkin’s transcription captured the suite’s essence and was beautifully performed here, it paled in comparison to Ravel’s orchestrations, especially in the icy perfection of Boulez’s performances.

If this first concert in CIM’s “The Boulez Legacy” series was an indication of what is yet to come, the concerts will be well worth the time to attend.

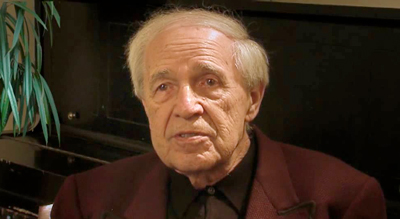

Image of Boulez from a Cleveland Orchestra Musicians video.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com September 27, 2016.

Click here for a printable copy of this article