by Mike Telin

The person Cleveland Orchestra principal keyboardist Joela Jones is referring to is none other than Pierre Boulez. “To me it’s amazing that somebody who is so great, so brilliant, and so gifted, could also be so humble and modest. He just makes you feel so comfortable, like you are his equal, which of course you’re not. And, if you have enough intelligence you know that.”

On Thursday, January 15 at 7:30 pm in Severance Hall, Franz Welser-Möst will lead The Cleveland Orchestra in a special musical celebration to salute Pierre Boulez’s 90th birthday. The concert will open with Boulez’s Douze Notations (for solo piano), with Joela Jones as soloist, and conclude with his orchestral versions of Notations I-IV and VII. The evening also includes Debussy’s Jeux and Berg’s Three Excerpts from Wozzeck with mezzo-soprano Michelle DeYoung and the Cleveland Orchestra Children’s Chorus. Beginning at 6:30 pm Cleveland Orchestra Archivist Deborah Hefling will give a pre-concert talk about Boulez’s fifty-year history with the orchestra. Prior to each work on Thursday’s concert, special video segments about Boulez’s nearly half-century relationship with The Cleveland Orchestra will be shown. Click here to view a Pierre Boulez 90th Birthday Celebration Concert Preview video.

Pierre Boulez has conducted The Cleveland Orchestra over a span of nearly fifty years. Since making his debut with the Orchestra in 1965, he has led the Orchestra in more than 220 concerts. He was appointed the Orchestra’s first Principal Guest Conductor in 1969 and served as Musical Advisor for two seasons beginning shortly after George Szell’s death in 1970. Additionally he has made several recordings with the Orchestra, and has won five Grammy Awards. In 2014 he was awarded the Orchestra’s Distinguished Service Award.

Joela Jones’s tenure as keyboardist with the orchestra began in the late 1960s. During a recent telephone conversation she recalled the astonishing number of works that she first played under Pierre Boulez. “I never really thought about this until recently, but I’ve played so many of the great works that involve keyboard for the first time with Pierre Boulez.”

That list includes, with the exception of Petrushka, every work of Stravinsky that has keyboard – Ives’s Three Places in New England – Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite, Valses Nobles et Sentimentales, Daphnis and Chloé – Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, Music for Strings Percussion and Celeste, Bluebeard’s Castle, the Dance Suite – Debussy’s Printemps and Jeux – the major works of Schoenberg, including Pierrot Lunaire – Carter’s Concerto for Orchestra, plus Berg’s Three Excerpts from Wozzeck.

Jones also considers Pierre Boulez to be her greatest teacher. “During the early ‘70s he used to do what I think were called ‘Informal Evenings with Pierre Boulez.’ He would take a work like Berg’s Altenberg lieder and dissect it for the audience. He’d talk about individual sections and then have the orchestra play. They were fascinating, and although I was in the orchestra, I felt like a student because I was so young. I would bring a notebook on stage and take notes because I didn’t want to forget anything. I even have pocket scores to all of those works I mentioned that are marked with his beautiful conducting patterns. He was more than a mentor and a great conductor — he really was a professor. I don’t necessarily think he would think of himself that way, but I certainly thought of him as the greatest professor I ever had.”

I asked Jones to talk about his conducting style. “He is so clear, clean and neat. I think that sometimes people think he’s just beating time, but it’s the nuance between the beats. And he does it with his hands because he doesn’t use a baton. It’s really remarkable and I’m sure he has influenced a lot of our finer young conductors.”

She also feels that Boulez has a special way of speaking to the members of the orchestra. “When he talks to the orchestra it’s always about what is in the score. Everything he says is based in what the composer wrote. And it seems so simple: just do what is in the score. Yet so many conductors and musicians complicate things by adding this and changing that, and sometimes making a mess of what the composer has written. But his approach is to just do what is there and when you actually do that, it sounds so wonderful.”

Joela Jones has also had the good fortune to make two recordings of works by Messiaen with Boulez. The first was Le Ville d’en Haut, and for the second, Sept haïkaï, she found herself having to learn the piece in a matter of days. “Pierre-Laurent Aimard was scheduled to play and record Réveil des oiseaux and Sept haïkaï. But I got a call from the orchestra management the Thursday before the first performance, saying that there had been a misunderstanding and his agent had neglected to mention he was supposed to play both pieces. Although he had played Sept haïkaï, he had no time to review it. So they asked me if I knew it — I said no. Then they asked me if I could learn it in time — I said that I would try.

Jones remembers getting the music that evening, and as luck would have it, the orchestra had been given the weekend off because of Presidents’ Day. “My husband Richard and I were planning to go skiing with our son, so they went without me and I stayed home and practiced about ten hours a day. I remember at the first rehearsal on Tuesday morning I told Mr. Boulez that I had just gotten the music and started learning it on Friday. He said, ‘Don’t worry Joela, it will be fine.’ With his calmness and his beautiful, clear conducting, the performances actually went very well, and we recorded it the following Monday. I remember how kind and wonderful he was to me at that first rehearsal. He’s a very calm person, and just being around him makes you calm. He made everything comfortable for me. It was a wonderful opportunity and I really appreciated it very much.”

Thursday’s concert opens with Boulez’s Douze Notations for solo piano (1945). “When I started learning them, I thought, boy, he has really restricted himself – each movement is 12 measures long and has 12 tones. But as I looked at them more, I thought, my goodness, for such restrictions there are so many facets to the music. The dynamic ranges go from triple pianissimo all the way up to triple fortissimo, and there’s tremendous variety in the tempos. The beautiful #5 is marked Doux et improvisé, yet #4 he wants very rhythmic and #10 he says to play mechanically. He has all of these tremendous contrasts and different emotions within this short frame of time. The entire piece only takes ten minutes to play, but the difficult thing about short pieces with so many contrasting moods is that you need to show a whole bunch of different personalities in a short period of time. I’m just trying to do what he wrote in the music.”

Wrapping up our fascinating conversation, I ask Joela how she will remember Pierre Boulez. “I will remember him for the kind of person that he is. As I said, it’s amazing to me that someone who is such a genius can be so kind and caring.” She went on to share the following story.

“On one of the occasions that Mr. Boulez returned to conduct, Petrushka was on the program. As you know, it is common for the conductor to give the pianist a solo bow at the end. After the Thursday night performance he only asked the entire orchestra to stand, and orchestra members were looking back wondering why he didn’t ask me to take a bow. I figured he had a lot on his mind and he just forgot. I didn’t care and I wasn’t devastated.

Later that night around 11:30 the phone rang. It was NancyBell Coe, who at the time was one of the managers. She told me that at the reception, Pierre Boulez was talking to some people and all of a sudden blurted out, ‘Oh no, I forgot to have Joela stand up,’ and he wanted to apologize. I said, for goodness sake, Pierre Boulez does not need to apologize to me. But Nancy said he was very upset with himself, and he wanted to be sure it was OK for him to call me at 10:00 tomorrow. I said absolutely. So I waited by the phone, and of course he called at 10:00 on the dot. He said, ‘I am so sorry – how could I be so stupid to forget to have you stand up.’ Of course I was melting on the other side of the phone. There was no need for him to do that, but that is the kind of person he is. He cares about everyone, and that’s what I will always remember him for. As well as for his musical genius as a conductor and a composer.”

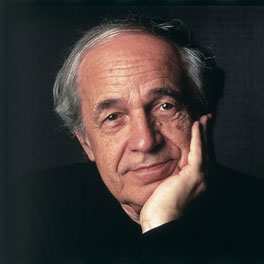

Photo of Boulez and The Cleveland Orchestra by Roger Mastroianni.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com January 13, 2015.

Click here for a printable copy of this article