by Mike Telin

On Thursday, October 13 at 7:30 pm at Severance Music Center, Kosower will once again move to the front of the stage. The work: Bloch’s Schelomo, Hebraic Rhapsody. Under the direction of Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider, the concert also includes Al-Zand’s Lamentation On The Disasters of War and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”). The program will be repeated on Friday at 11:00 am, Saturday at 8:00 pm, and Sunday at 3:00 pm. Tickets are available online.

I caught up with the Wisconsin native by phone and began our conversation by asking him when he first encountered the Rhapsody.

Mark Kosower: I’ve known about it since I was a boy. My father’s a cellist, although I don’t think he performed it very much. My first time performing it was in 2007 when I had the chance to play it with the Spokane Symphony in Washington with Gunther Schuller conducting. It was a wonderful and interesting experience.

Mike Telin: When I was a teenager I bought a recording of it — I turned it on and it just grabbed me right away.

MK: Exactly! The piece has a very specific sound world that’s incredibly striking and almost has a hypnotic quality about it. It’s part of his Jewish Cycle of pieces. He was drawing on a lot of different influences and at the time was searching for his own musical voice, as well as a musical voice for the Jewish people.

There’s a lot of Middle Eastern influences — augmented seconds and the occasional quarter tone. He also loved Wagner and Strauss, so there’s a lot of very dense chromaticism, and the piece is very densely orchestrated.

I would say a third influence would be that of Claude Debussy and the French impressionists in terms of harmonic progressions that don’t necessarily resolve.

It was written in the 19-teens [1916] which was the age of extended tonality, whether you’re talking about Max Reger in Germany or about the works of Fauré. And while it isn’t extended tonality in every sense of the term, I think that helps to portray the work’s unrest and the message that Bloch [below] is trying to portray from the Book of Ecclesiastes, which is that nothing is worth the pain it causes, all is vanity.

The unrest in the music also reflects what was going on in the world leading up to the First World War.

MT: What are the interpretive challenges? It is a very big piece that calls for a huge orchestra.

MK: It’s called Hebraic Rhapsody, so anytime you have a rhapsodic piece you want to try to organize it in a way that brings as much clarity as possible — it would be very easy for a piece like this to become nebulous, not knowing where you’re going to or coming from. So understanding how the different parts relate to one another is very important.

It’s also a real ensemble piece and there are some challenging rhythmic areas that take some sorting out. That is something we’ll tackle together during rehearsals.

MT: The piece begins with a long A in the cello — how do you pick it out of the air?

MK: It’s in a position on the instrument that we call the three-finger position, and the harmonic A is there. And believe it or not, what always helps you find the pitch the most is your ear, so it’s that, combined with muscle memory from having practiced. But mostly it’s hearing the note, which is fascinating to me because it’s not a physical thing by itself, but it’s what guides the hand to the right place.

MT: Also, unless you have a score, it’s difficult to tell if the first note is rhythmically notated or if the soloist has discretion as to how long it should be held.

MK: That’s an astute observation. The answer is both. It’s in 9/8 and it’s a dotted half note, tied to a dotted quarter note, with a fermata over the dotted quarter note. So because of the fermata there’s not a precise amount of time. And in performance it can be exaggerated or maybe even a little shorter depending on how you interpret the opening phrase.

MT: Are there any particular sections that you wish would go on longer?

MK: I guess when it goes into D major near the end — I wish it went on a little longer but I understand why it doesn’t, because it’s just a glimpse into the afterlife and that’s not the main message of the piece.

MT: Bloch described the piece as “psychoanalysis of his unconscious creative process.”

MK: And he said there was no program or written-out story for the work. But what he did say is that the cello represents the words of King Solomon, and the orchestra represents the world around him — his experiences in the world and sometimes his inner thoughts.

MT: Do you create a storyline?

MK: When you’re interpreting a piece of music you’re always trying to figure out what the different musical material represents. So in a sense we’re always coming up with a story or an image depending on what we think the piece is trying to express. So I guess the short answer is yes.

MT: Where does Schelomo fit into the grand scheme of cello concertos such as Elgar, Haydn, Dvořák, and Tchaikovsky?

MK: It is definitely one of the great works for cello and orchestra, and many people regard it as the best work that Bloch ever wrote. I think it has a striking sound world and is full of imagination. And just how poignant and strong the message is — I think that’s really what sets it apart from most pieces. There’s just something — I think the right word is captivating — about it. It really is a powerful work.

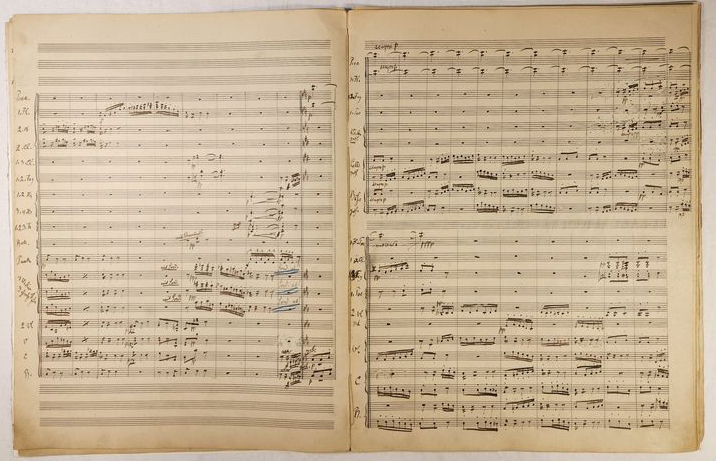

MT: Changing topics slightly — it must have felt good to be back with Mahler 2 and the score?

MK: I think everybody was really moved when Franz announced the gift to the Orchestra. And just to get to see the score of Mahler 2 in the composer’s handwriting really leaves an impression. But it is great to be back and I thought the concerts were extraordinary.

MT: The Orchestra also had a successful tour.

MK: It was fantastic to be in Europe again. I figured out that the last time we were there would have been Vienna in May of 2019 for the centennial tour. It was wonderful to be back playing, being in those great cities and halls, representing Cleveland, and just making music on the road again.

But it’s also great to be back — as we heard this week, there’s nothing like the hometown fans.

MT: Is there anything you’d like to add?

MK: I’m just really excited to get to play this incredible work with our orchestra and with Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider. He’s a wonderful musician and exudes the same leadership on the podium as he does as a soloist. It’s going to be great.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 6, 2022.

Click here for a printable copy of this article