by Lilyanna D’Amato

Acutely aware of the classical tradition’s discriminatory leanings, Price was direct. She desperately needed Koussevitzky to program her compositions. The work of a woman composer is predetermined, she said, “to be light, froth, lacking in depth, logic and virility… add to that the incident of race — and I hope you will understand some of the difficulties that confront one in such a position.”

At that point in her career, she had already achieved unprecedented success. The first-prize winner of the 1932 Wanamaker music contest and the first Black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra, she was a distinguished member of the Black intelligentsia, fraternizing with the likes of W.E.B. Dubois, Langston Hughes, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. She had received national acclaim for her nearly faultless virtuosity, and yet, she never heard back from Koussevitzky.

Unfortunately, this lack of critical recognition defined her career. For in her lifetime — and in the decades following her death — she was excluded from the higher, white echelon of the classical canon, although her music continued to be performed, celebrated, and studied in Black classical music and regional communities.

Born in a racially integrated neighborhood in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887, Price grew up in a middle-class household — her father was the city’s first Black dentist and her mother a schoolteacher. At the age of four, she played in her first piano recital, writing her first composition at eleven. Encouraged by her mother, she left home at fourteen for the New England Conservatory, one of the few conservatories that admitted Black students at the time, returning three years later to teach and raise a family.

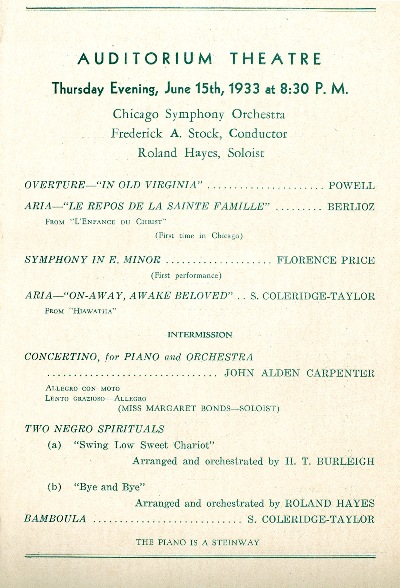

Her early adulthood in Arkansas was oppressive; as racial tensions mounted, lynchings became routine, and, additionally, her husband was abusive. During this time, she composed a few short pieces and songs for children, but, on the whole, her compositional output was small and unpretentious. However, in 1927, the tide began to turn. She divorced her husband and moved her family to Chicago, where she increasingly essayed larger symphonic and concertos, winning support from the music director of the Chicago Symphony, Frederick Stock. On June 15th, 1933, she became the first black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered her Symphony No. 1 in E minor in a concert titled “The Negro in Music.”

This radical incorporation of Black folk music in concert and choral pieces alike served to rectify the presence of blackness in a white, Western medium, expanding an African American intellectual discourse which followed in Dvořák’s footsteps. Her work, she writes in a 1943 letter to the conductor Frederick Schwass, “is intended to be Negroid in character and expression… None of the themes are adaptations or derivations of folk songs. The intention behind the writing of this work was a not too deliberate attempt to picture a cross-section of present-day Negro life and thought with its heritage of that which is past, paralleled or influenced by contacts of the present day.”

In an interview with The New York Times’ Micaela Baranello, Marquese Carter, an Indiana University doctoral student who specializes in Price’s work, said that her work “uses the organizing material of spirituals… [she] is a representation in music of what it means to be a black artist living within a white canon and trying to work within the classical realm.” Later in the interview he asks, “How do we, through that, create a sound that sounds our culture, sounds our experience, sounds our embodied lives?”

He asks the vital question: how do Black composers communicate their experiences through an artform which has historically ignored or sidelined them?

In this series, as we continue to celebrate past Black composers whose voices went largely unheard and uncelebrated, this is a question we must consider. In doing so, we also must reconcile with the current culture of classical music: one which is not all that dissimilar from the tradition that Florence Price encountered in her lifetime. We must ask ourselves how classical music needs to change, whose experiences must it include, and — to echo Carter’s question — how that will alter what has traditionally been recognized as the “classical sound.”

Throughout her life, Florence Price was repeatedly pushed aside by the higher-ups in the industry; her fourth symphony was nearly forgotten until it was miraculously discovered in her former Chicago summer home in 2009, a masterpiece almost wholly omitted from history. How does the inclusion of her voice in the canon change the state of classical music?

What other voices have we ignored for far too long?

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 29, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article