by Lilyanna D’Amato

“The Legacy of Black Classical Music” hopes to remind us of those musicians and composers whose voices went largely unheard, whose careers were left obscured by the pernicious disease that is systemic racism. In this weekly series, we will explore the lives and contributions of Shirley Graham Du Bois, Florence Price, Josephine Baker, William Grant Still, and Joseph Boulogne (Chevalier de Saint-Georges) — rich and valuable lives largely omitted from Western music history. Let us listen and learn together, celebrating their mastery while also taking the time to critically consider our own complacency in their erasure. For, in this admission lies the beginnings of vital change.

The first musician on our list is Shirley Graham Du Bois, whose tenacity, creative ferocity, outspoken personality, and intellectual prowess led her on a career spanning the globe. Born in Indianapolis in 1896, she spent her childhood immersed in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, where her father served as a preacher and activist.

In his biography of Graham Du Bois, historian Gerald Horne recounts one of the composer’s most meaningful memories of her father: as he stood with a loaded gun and a Bible, preparing, along with twenty-one armed men, to defend his congregation from an angry white mob.

In the end, no mob arrived, but young Shirley was forever imbued with his devotion to protecting his community, using his voice to defend the rights of Black people everywhere. This sense of responsibility to her communities, a desire to look beyond the finite limitations of her life in search of shared racial uplift became her life’s defining feature, earning her the title “Race Woman.”

Author and activist Brittany Cooper describes Race Women as “the first black female intellectuals… public thinkers on all phases of the race question” solely vested in the communal betterment of black people. In her early life, Du Bois turned to music for the answer.

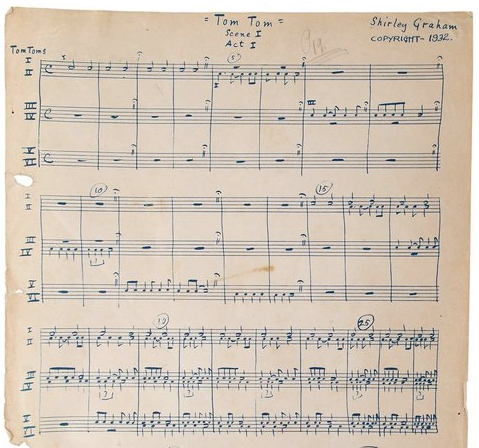

After attending classes at Howard University’s School of Music, her talents led her to the Sorbonne in Paris in 1926. There she composed the musical score and libretto of her opera Tom Tom: An Epic of Music and the Negro, her most celebrated work.

In 1931, after she had raised two children and divorced her first husband, she studied at Oberlin College, during which time Tom Tom premiered at Cleveland Stadium. The first two performances drew an audience of over 25,000, including Ohio Governor Newton Baker. Featuring an all-Black cast and orchestra, it became the first work of its kind to be produced on such a scale and the first opera by an African American woman to be staged, serving as a pivotal moment in African American classical music.

Since then, it has never again been performed in its entirety, although Cleveland’s Karamu House, the nation’s oldest African American Theater, has performed excerpts in the past. This will soon change, though, as Oberlin College has announced it will stage Tom-Tom in the fall of 2021 in tribute to its alumnus.

The opera sonically traces the African Diaspora through separate iterations of the same six central characters. Beginning with an overture composed solely of six tom-toms, the opera opens in an African Village as the villagers prepare for the sacrifice of “The Girl” but are ultimately captured and enslaved. Now criticized for its exoticized portrait of tribal life, Act I feels similar to the highly racialized depiction of Africa in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, published twenty years earlier. The audience at Tom Tom’s premiere, however, would not have been surprised by this depiction of Africa, for popular culture at the time was brimming with romanticized portrayals of people of color.

Act II jumps ahead several hundred years to an American slave plantation, where the characters reconcile with their forced migration. The musical score is composed of African American spirituals, echoing the characters’ search for salvation, their loss of their ancestral homeland, and their disagreement over whether to cling to ancient vodoun polytheistic religion or to accept Christianity.

The third act opens in the industrialized Harlem of the 1920s as the characters continue their generational disagreement over religion. The Voodoo Man convinces a few of the younger characters to return to Africa, but, ultimately, their plan is muddled by capitalistic greed and fracturing within the black community, a clear reference to the “Back-To-Africa” Movement of the 19th century. Marked by jazz, cabaret, and blues music, the score offers a musical portrait of contemporary African American life, perhaps distinguishing the differences between African and African American experiences while acknowledging their innate sameness.

In Tom Tom, Graham Du Bois communicates a deep commitment to reconciling African music in a contemporary, American context. Much like in her Oberlin master’s thesis, Survivals of Africanism, she examines the origins and value of African polyrhythm to identify its musical and cultural influence over popular music of the 19th and 20th centuries. In 2020, as Hip Hop and Rap dominate the charts, her claims feel especially pertinent.

While she would continue to compose throughout her life, predominantly setting her brother’s poetry to music, her commitment to racial justice began to evolve after her graduation from Oberlin. In 1942, she became the Director of Fort Huachuca, a military base in Arizona which housed fifteen-thousand black soldiers. Later in the 1940s, as the NAACP’s membership increased tenfold, she worked tirelessly as an assistant field director in New York City. At the same time she penned her first biography, Dr. George Washington Carver, Scientist, continuing with a biography of Paul Robeson and a profile of Fredrick Douglass a few years later. She would continue writing throughout the 1950s, earning both the Messner and Anisfield-Wolf writing prizes for her work in fiction.

As the second Red Scare took hold of the country in the years following World War II, the Du Boises, both communist advocates, fled the country for Ghana. There they served as advisors to the country’s first President, Kwame Nkrumah. When Du Bois died two years later, Graham Du Bois remained in Accra until the overthrow of the Ghanian leader in 1966, then traveled throughout Africa, Asia, and Europe to advocate for anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism. After a long battle with breast cancer, Graham Du Bois died in Beijing, China in 1977.

Forgotten and uncelebrated, her extraordinary life is a lesson in resilience, in self-actualization, in the exploration of every facet of the self, and, most importantly, in privileging community over the individual. Shirley Graham Du Bois’ unwavering commitment to uplifting Black voices became her life’s work, the underlying aim of everything she achieved. While her musical and intellectual contributions have gone largely unnoticed, ignored as a result of pervasive racism, and overshadowed by the work of her highly acclaimed husband, Graham Du Bois’ prolific legacy renders her an artistic pioneer, a risk taker, and, undoubtedly, a “Race Woman.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com July 1, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article