by Kevin McLaughlin

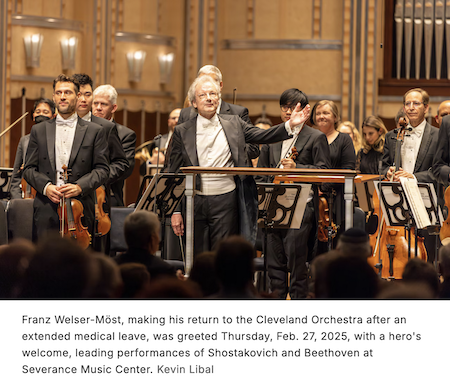

CLEVELAND, Ohio — Franz Welser-Möst was greeted with a hero’s welcome at Severance Music Center on Thursday, February 27, by the large and appreciative audience — even before a note of Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony had been played. He acknowledged the genuine warmth in the room, and the occasion of his return to the podium after a medical leave.

Opening the program was Shostakovich’s wintery Violin Concerto No. 2, with Leonidas Kavakos as soloist. It’s a mostly gloomy work not easily shaken from its brooding until the Finale — and even then, the raucous dancing is more crazed than jubilant.

The fine program notes by Peter Laki point out that Shostakovich’s late compositions have been closely examined for their hidden meaning or coded messages between composer and audience. Indeed, the score of the Second Violin Concerto, which may or may not be political, seems to contain various embedded cris du coeur waiting to be recognized: drum hits (= gun shots?), flute solos (= freedom’s proxy?), march tunes and folk tunes (= possible resistance against the Soviet regime?). But as for their plain meaning, David Rothenberg in his pre-concert lecture summed it up: “Who can tell?”

Leonidas Kavakos is a striking presence onstage. His long, straight hair, lanky frame, and almost supernatural violin tone imbued a dark and disturbing atmosphere. He was impressive in the lyrical opening, offering the right amount of sadness and introspection. Each of the three movements’ cadenzas benefitted from Kavakos’s smart pacing and storyteller instincts. The Adagio was quite wonderful, with long-lined phrasing and more intense violin tone, even in the softest passages. In the last movement,Welser-Möst’s sensitive, light touch carried the day, enhancing Shostakovich’s aggressive grotesquerie.

Kavakos rewarded the attentive audience with an encore: the Sarabande and Double from J.S. Bach’s B minor Partita.

After the intermission, Welser-Möst made a rare announcement from the podium. He said he was grateful to be back and appreciated the affection. Then he quickly deflected attention to announce the recent passing of Clara Taplin Rankin, a longtime member of the orchestra’s Board of Trustees, at the age of 107. The performance of the Beethoven Symphony was dedicated to her, a person “full of humanity, intelligence, and joy.”

Welser-Möst’s Eroica was both lyrical and hyper-charged. He drew a performance that was urgent, fiery, and gorgeous, and the orchestra was set to eleven. Tempos were generally fast, providing a sense of both danger and thrill. String playing was crisp and clear. The horns (aside from one uncharacteristic fluff) were glorious, reveling in their hunting horn spotlight in the Trio of the Scherzo and at the climax of the funeral march. The trumpets, too, generated waves of excitement in their big moments.

Cellos and double basses brought enormous breadth and volume that energized the rest of the orchestra. The variations in the finale were buoyant, with some magnificent flute playing by Jessica Sindell. The arrival at the finish line by the full ensemble was exuberant. Welcome back, Franz.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 5, 2025.

Click here for a printable copy of this article