by Daniel Hathaway

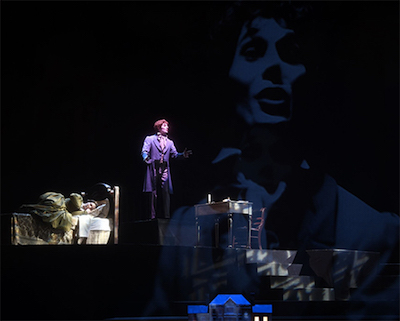

His Oberlin Opera Theater production, which opened for four performances last week in Hall Auditorium, frames the entire action behind a gauzy scrim. Projections layer ectoplasmic images over the dimly-lit figures of the former valet and governess of the manor house named Bly who return after their violent deaths to lay claim to the souls of the children Miles and Flora. No, the Governess isn’t making things up!

There’s still plenty of ambiguity left in Myfanwy Piper’s libretto, based on Henry James’ novella of the same name. Evil has visited this country manor house, and although strong hints of sexual exploitation are dropped, they’re referred to obliquely, but never named. Young Miles is expelled from his school (“an injury to his friends”). In a Latin lesson, he turns rhymes meant to help memorize the gender of nouns into sniggering innuendo, and invents a creepy song he calls Malo. After catching fleeting visions of the two dead servants, the Governess concludes that “…things have been done here that are not good, and have left a taste behind them.”

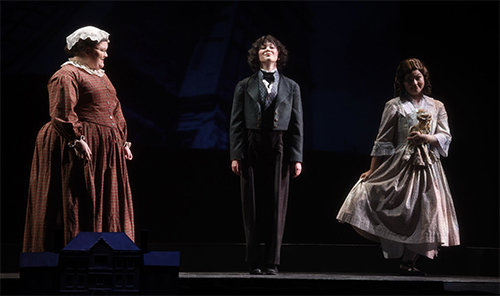

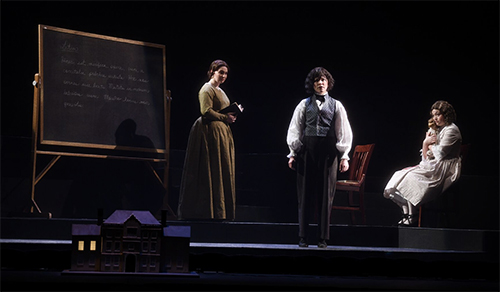

Field’s staging also suggests rather than bespeaks. Scenic designer Laura Carlson-Tarantowski’s platforms and minimal furniture make up the set, its only striking feature a scale model of the manor house whose windows light up to indicate where the action is taking place. Jeremy K. Benjamin’s lighting subtly isolates the opera’s many scenes and adds a touch of surreal imagery. Only Chris Flaharty’s handsome period costumes are fully realized.

Economy characterizes the music as well. Britten’s lean and frequently chilling score calls for a chamber orchestra of only thirteen players, but it brilliantly underscores the onstage events. Though only subliminally apparent to the listener, the whole opera is in theme-and-variation form, its music derived from a spiraling, twelve-tone row that creates an undercurrent of dramatic tension. Conductor Christopher Larkin and his one-player-on-a-part ensemble were flawless on opening night, Wednesday, March 7. Everyone was a soloist, but percussionist Samuel Hoffacker was particularly impressive on a variety of instruments, and pianist Emilija Rozukaite produced great flurries of notes for Tori Adams to pantomime to during Miles’ headbanging piano lesson.

Wednesday’s cast was similarly strong on the vocal front (that group returned on Saturday, while a second cast took the stage on Friday and Sunday). After the scene-setting Prologue, dramatically sung by Conor Brereton, the clear-voiced Caitlin Aloia introduced herself as the Governess in an expressive monologue enroute to her new job.

Whitney Campbell, as Mrs. Grose the housekeeper, met her at the front door of Bly, introducing the Governess’ new charges, Katherine Lerner Lee as Flora and Tori Adams as Miles. Campbell made for an appropriately matronly worrywort, and Lee and Adams were entirely credible acting and singing the roles of children, Lee capturing the fussiness of a doll-toting child, and Adams nailing the personality of an impish young boy.

Peter Quint and Miss Jessel were arrestingly spooky from their first appearances at the tower and across the lake. Quint, sung alluringly and with astonishing control by Nicholas Music, was just as the Governess described him: “…tall, clean-shaven, yes, even handsome. But a horror!” The “lovely Miss Jessel,” played by Cara Bender, was substantial in voice but sepulchral in visage. In a subsequent manifestation, they comically emerged from under the Governess’ bed, adding humor to the hideous.

As the screw of the plot turns, Quint’s and Jessel’s influence over Miles and Flora grows more intense, and the nature of their power increasingly explicit. Finally, Miles owns up to stealing a letter the Governess has written to the children’s guardian detailing all the strange events at Bly. Encouraged by the Governess, Miles exorcises the former valet by calling him by name: “Peter Quint, you devil!” Miles dies in her arms while she sings his Malo song.

Not a happy Mozartian finale, but gripping. Oberlin Opera Theater’s The Turn of the Screw added up to a riveting evening of music drama that could stand up proudly to most professional productions.

Photos by Yevhen Gulenko.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com March 15, 2018.

Click here for a printable copy of this article