by Jarrett Hoffman

•Tonight: Cleveland Orchestra plays Berg and Schubert

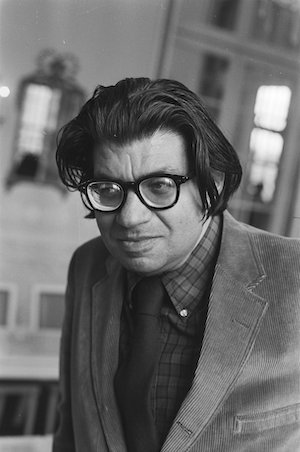

•News: Jejuana C. Brown (pictured) joins the Orchestra as Director of Diversity & Inclusion

•Almanac: Morton Feldman and his important decision to leave a concert early

HAPPENING TODAY:

Tonight at 7:30 pm, Franz Welser-Möst and The Cleveland Orchestra will be joined by Joélle Harvey (soprano), Daryl Freedman (mezzo-soprano), Julian Prégardien and Martin Mitterrutzner (tenors), Dashon Burton (bass-baritone), and the Cleveland Orchestra Chorus for a program that includes Berg’s Lyric Suite and two works by Schubert: the Symphony No. 8 and the Mass No. 6. Interestingly, the movements of the Berg and Schubert 8 are interwoven — Berg, Schubert, Berg, Schubert, Berg. Take a look here, where you can also find tickets. It’s the first of three performances over the coming days.

IN THE NEWS:

Earlier this week, The Cleveland Orchestra announced the hiring of Jejuana C. Brown as Director of Diversity & Inclusion. In this newly created position that reports directly to the Orchestra’s President & CEO, Brown will develop “a comprehensive equity, access, diversity, and inclusion plan that aligns with the Orchestra’s objective to promote diversity as an essential element of the organization’s core values, goals, and mission, which is to inspire and enrich lives by creating extraordinary musical experiences at the highest level of artistic excellence.”

Brown has previously been Director of Inclusive Culture & Talent Initiatives at Greater Cleveland Partnership, and led strategic projects for several departments at her alma mater, Cleveland State University, where she earned a Master of Education in Adult Learning and Development and a Graduate Certificate in Diversity Management. She is currently pursuing her Doctorate of Executive Leadership at the University of Charleston (West Virginia) and serves on the boards of the Journey Center for Safety & Healing, Cleveland Society for Human Resource Management, and Facing History & Ourselves (Cleveland).

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

Feldman’s close association with John Cage is well known, as is the influence of Abstract Expressionists on his music — and those two facts are related. It was through Cage that Feldman was introduced to such artists as Robert Rauschenberg and Sonja Sekula.

And how did Feldman meet Cage? Here’s where that impulse comes in — it was at a concert by the New York Philharmonic, in the lobby, after both had decided to leave following the audience’s disrespectful reaction to Anton Webern’s Op. 21 Symphony. (They did not stay for the following work, which depending on the account was either by Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff.)

If only we could all know when in life impulsiveness is a good thing! (I guess then it wouldn’t be impulsive…) Anyway, Feldman chose wisely.

Before reading further, let’s do an experiment — take a moment to listen to a little bit of Feldman’s Intersection I (1951), just enough to get a taste.

Did you do it? I’m waiting…

At the encouragement of Cage, Feldman began to develop nontraditional, graphic forms of notation that left such elements as pitch up to the choice of the performer. In Intersection I, as Samuel Clay Birmaher writes in an article for New Music USA,

Notes are represented by boxes on a grid. Pitches are not specified; instead, the vertical placement of the box represents the low, middle, or high range of the instrument, from which each player individually selects a note. Players on the same part begin notes on their own, but release together…

Understanding how the notation functions can make a big difference in following along with and appreciating the music. Listen again and see what you think.

You can’t do Feldman justice without noting his late style of extreme length in his music. As Tom Service writes in an article for The Guardian, after listening to these works,

My sense of time had been altered, so intently focused was I on the way the music changed from note to note and chord to chord…You don’t really listen to these pieces, you live through them and with them. By the end of the Second String Quartet, I felt it was living inside me too.

Even without listening to all 84 minutes of the 1985 Piano and String Quartet, you can get a strong sense of what Service means by that. Listen here.