by Peter Feher

CLEVELAND, Ohio — There’s never been a better time to buy a couple of extra tickets to The Cleveland Orchestra.

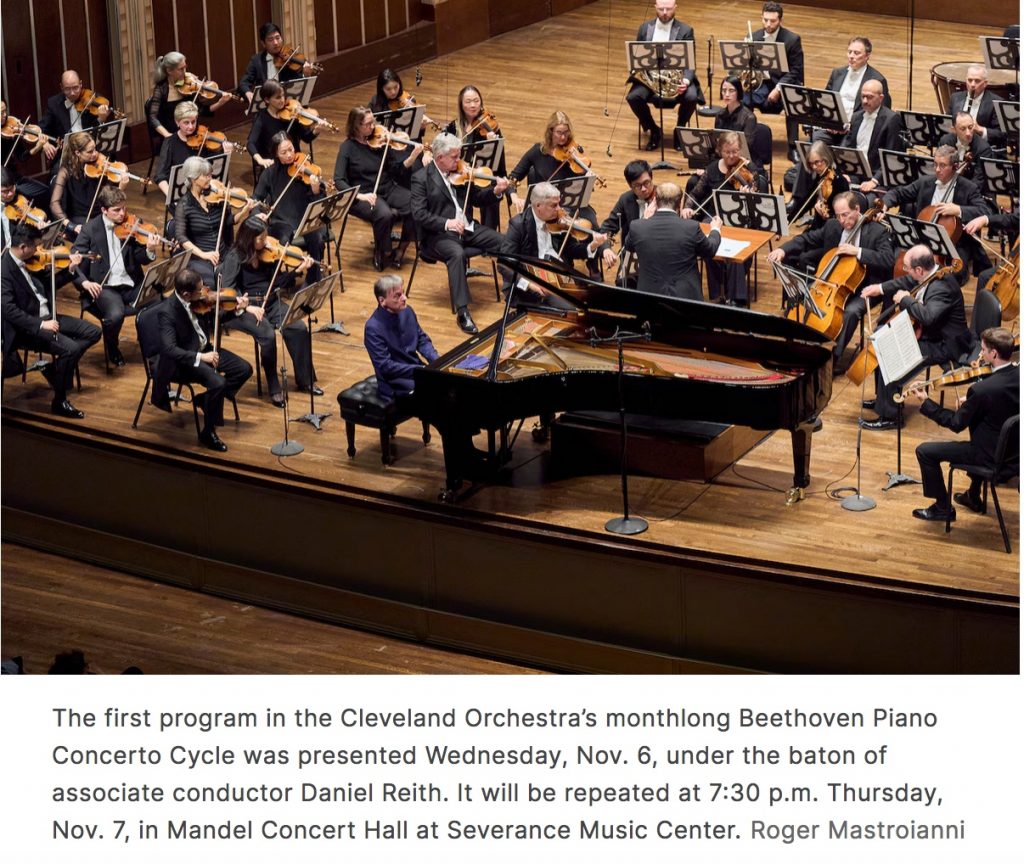

Not one but four stellar soloists took the stage at Severance Music Center on Wednesday, Nov. 6 — representing about half of the star-studded lineup coming to Cleveland over the next two weeks. The big event of the Orchestra’s fall season, a complete cycle of Beethoven’s piano concertos, is set to feature a different headliner for almost every piece.

This wasn’t the original plan, but with music director Franz Welser-Möst undergoing medical treatment and unable to conduct — and the scheduled soloist for the entire cycle, Igor Levit, withdrawing as a result — the Orchestra had to adapt. The personnel changes were announced on Monday, Nov. 4, including associate conductor Daniel Reith’s stepping in to lead all the performances, which run through Nov. 17.

What was supposed to be a marathon has become something of a mini festival, which is good news for committed and casual concertgoers alike. Any pianist will tell you that choosing a favorite Beethoven concerto is impossible. Offering a mix of performers is an invitation for audiences to experience even more of this essential repertoire.

For its sheer variety of soloists, the opening program of the cycle couldn’t be beat. Pianist and Northeast Ohio native Orion Weiss joined the previously scheduled lineup of violinist Augustin Hadelich and cellist Julia Hagen in a polished performance of Beethoven’s Triple Concerto on the first half of Wednesday’s concert.

The trio’s virtuosity helped carry the piece, which in lesser hands can sound somewhat pale. Beethoven’s extraordinary decision to score a concerto for this combination of instruments doesn’t automatically make for exciting music. Much of the material is repetitive — appearing first in the cello, then in the piano’s left hand, then in the violin, then in the piano’s right. The story goes that the composer wrote an easier keyboard part for a young patron and more difficult violin and cello parts.

The strings sustain the piece, and Hagen, making her Cleveland Orchestra debut, soared in the lofty melodies that permeate each movement. Hadelich sweetened every phrase he touched. With Weiss supplying the bravura, the three players traded solo lines back and forth — in competition, in agreement, in jest — always working to find the meaning within each repetition.

Sir Stephen Hough had the evening’s second half to himself, soloing in the Third Concerto, a sensible place to continue the cycle. This work showcases all the sparkle of Beethoven’s early period, starting with a first movement that, cadenza aside, could easily be mistaken for Mozart. Yet the piece also foreshadows musical developments to come, notably in its choice of key, C-minor, which held an almost fateful significance for Beethoven.

Hough struck a miraculous balance between styles, often to otherworldly effect. In the Largo second movement, he played so softly that time seemed to stop while he nonetheless kept the tempo rolling. Tasteful moments of understatement stood out in his interpretation, even amid the extroverted gestures of the finale. Throughout, Reith deferred to the pianist and coaxed a beautiful sound from the Orchestra in support.

For an encore, Hough performed Frédéric Chopin’s Nocturne in E-Flat Major Op. 9, No. 2 — a bit of a break from Beethoven, he said.

You couldn’t keep the pianist away from the stage, explained André Gremillet, the Orchestra’s president and CEO, before the concert’s second half. Hough had suffered an injury at his hotel earlier in the day, but he wasn’t about to call for a substitute if he could help it.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com November 14, 2024.

Click here for a printable copy of this article