by Daniel Hathaway

The second week coincides with Oberlin’s Summer Trumpet and Percussion Institutes, so there are new groups on campus vying for rooms in an already tight situation because of construction. Harpsichordists showed up for their master class to watch a group of percussionists discussing the finer points of tambourines. Trumpeters are taking over the Methodist Church next door.

Since rooms are at a premium, you can encounter groups using every available space — like the gaggle of theorbos meeting with Lucas Harris in the lobby of Warner Concert Hall (above).

One of the oddities of BPI is that you have to arrange meals on your own. Most summer institutes offer a communal dining plan that encourages camaraderie as well as nutrition, but during these two weeks in Oberlin you have to strike up conversations and launch friendships in different ways.

After a few days, kindred spirits find each other, as did a group of us who sat together during last week’s faculty concert on Friday evening. We kept our seats during intermission, and the conversation turned to Talcott Hall, the hulking 19th-century stone pile right across the street where most of us are billeted. Built in 1886 as a residence for women, it now houses students of all genders from second year up who regard it as prime dormitory real estate.

Someone else noted that he’d explored Talcott’s rather creepy basement while checking out the laundry room, and another said, ‘There’s an attic too — the door is right next to my room with a padlock on it. But I haven’t heard any spooky sounds up there — yet.” That was the day before the bat began flying around over our heads. Final observation: “Have you looked inside the refrigerator in the second floor kitchen? There are no shelves! The food is just piled up.” Welcome to dormitory life. But the rooms are huge, with high ceilings and big windows. It was good advice to bring a fan.

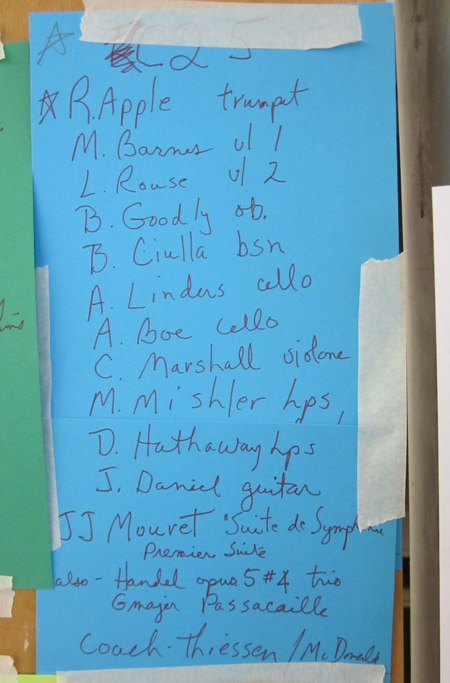

But back to Baroque music. On Monday morning, the faculty re-huddled on the Warner Concert Hall stage to make up ensembles for the second week. Last week’s student concert included performances by 20 groups. Week two will feature only 14, but many of those ensembles will be larger than before. My group includes two violins, oboe, trumpet, and a continuo section of two cellos, bassoon, double bass, guitar, and two harpsichords, and the main work — familiar to fans of Masterpiece Theater — is the first suite from Mouret’s Suites de Symphonies, to be coached by the early trumpet expert John Thiessen. As a bonus, my friend Ana Boe is one of the cellists.

A virginal came into play for Peter Phillips’ keyboard version of Caccini’s Amarilli de Julio Romano. Pointing out the arrangement’s relationship to lute music, Lisa Crawford counseled the student to define which part of music was part of the song and which was a flight of ornamentation. She said that the “dripping fingers” hand position you see ladies using in contemporary illustrations works well on the short natural keys of the instrument.

Monday’s ensemble coaching session proved that the large continuo department needed to deploy its forces strategically. We added the lovely Passacaglia from Handel’s Opus 5, No. 4 sonata to our program and gave it a readthrough.

The evening’s continuo class dug back into the issues of voice leading — how well-behaved voices move between chords. Joe Gascho’s three rules: voices don’t move at all unless they have to; if they do, they should move stepwise; and they should always avoid creating parallel fifths and octaves between pairs of voices.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com June 29, 2017.

Click here for a printable copy of this article