by Daniel Hathaway

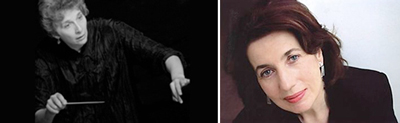

The burning question after The Cleveland Orchestra’s concert on Thursday April 24 was why it took so long to bring conductor Jane Glover and pianist Imogen Cooper — either singly or together — to Severance Hall. The two British artists collaborated to produce a spectacular performance of Beethoven’s first concerto, and Glover led pristine and loveable readings of sinfonias by C.P.E. Bach and Johann Baptist Waṅhal* as well as a finely shaped account of Haydn’s “Drum Roll” symphony.

Glover set up a bright, sprightly introduction for Cooper in the Beethoven (the pared-down string section allowed the orchestra to play with amazing transparency). Responding with verve and an effortless elegance, Cooper breezed through her passagework, made perfect joins with Glover and the orchestra and pointed up exquisite moments like the sudden shift into E-flat. The recapitulation of the first movement was announced by a surprising blaze of horns and Cooper’s initially calm, orderly cadenza suddenly jolted the ear with wild chord juxtapositions. “She’s fantastic!” cried a woman in the row behind me. No shushing and no argument there.

Cooper said in an interview with this publication that she and Glover met in London to talk through the concerto and decided just for fun to try the second movement in the key of G rather than Beethoven’s eccentric choice of A-flat. Verdict? Beethoven was right, and so he proved to be once again at Severance Hall, where Cooper’s marvelous shaping of phrases — along with expressive solos by flutist Saeran St. Christopher and clarinetist Franklin Cohen — also made the slow movement something special.

Was that a gasp we heard when Glover started the finale? It was fast — and as light as a good soufflé — but that was no problem for Cooper, who once again brought her flawless technique to bear. Glover drew propelling inner rhythms from the orchestra that often go unheard, and conductor and pianist gave special attention to the key change after the cadenza. Beethoven No. 1 is always delightful to hear but this performance was a standout. The audience warmly called pianist and conductor back for several bows.

Though wildly popular in Berlin in his day, Carl Phillip Emmanuel Bach isn’t heard so often in today’s concert halls, even in concerts by period ensembles. His Sinfonia No. 2 in E-flat, which opened Thursday’s concert was, in fact, a first performance for The Cleveland Orchestra. In the hands of a conductor like Jane Glover who obviously admires his music, C.P.E. Bach can sound quite fresh and inventive. This sinfonia opened with enough trilling back and forth between violins and winds to bring smiles to faces. Glover made the music thrive by adroitly shaping its phrases and surges.

A bit of humor preceded Waṅhal’s Sinfonia in g minor after intermission, when a librarian appeared a bit late with the score and garnered a round of applause. The Bohemian composer’s sinfonia (he wrote it in Vienna) was agreeable but unmemorable except for a lovely violin and viola duet during the trio of the minuet (Peter Otto and Lynne Ramsey) and some stirring violin passages in the final Allegro.

The third symphony on the program was Haydn’s 103rd, a masterful piece played magisterially by Glover and The Cleveland Orchestra, who sculpted its phrases with distinction, brought out its surprising harmonic contrasts and rejoiced in its jokes — like the beginning of the finale where the violins seem to have forgotten to play, hanging the accompanying horns out to dry and requiring another start. A marvelous ending to a concert distinguished by some of the best ensemble playing you’ll ever hear anywhere.

* As the composer spelled his name. In the 20th century, he suddenly became Jan Křtitel Vaňhal, a modern Czech rendering printed in the program.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com May 6, 2014.

Click here for a printable copy of this article.