by Daniel Hathaway

Kent State University musicology professor Theodore Albrecht, who is deep into translating relatively unexplored Beethoven documents, has turned up some surprises. Among them is the suggestion that Beethoven could still hear — if not well — at the premiere of the Ninth. “All the stone-deaf Beethoven stories go out the window,” the scholar said in a recent telephone interview.

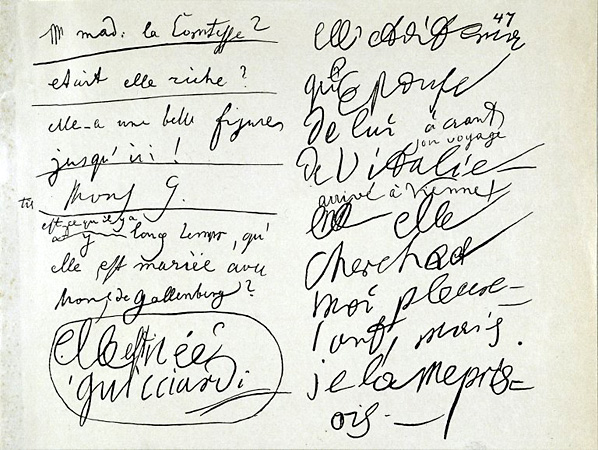

That and other discoveries have come to light in the course of Albrecht’s current research project: translating Beethoven’s 139 “Conversation Books” for the first-ever English edition. As he notes in an article scheduled to appear this spring in the Beethoven Journal,

By 1818, Beethoven’s deafness had progressed to such an extent that, with increasing frequency, he began to carry blank books with him, so that his friends and acquaintances, especially when in public, could write their sides of conversations without being overheard, while Beethoven himself customarily replied orally. He, too, wrote in them — shopping lists, errands to run, or books advertised in the local newspapers.

At an American Musicological Society meeting, he was huddled with some of his fellow academics when one of them asked him what his next project would be. He replied that he was working on personnel lists from Vienna premieres of Beethoven’s works. “How about translating the conversation books?”

“Oh, no,” Albrecht said, gesturing toward Beethoven scholar Lewis Lockwood. “That’s his job, he’s working on that.” Lockwood demurred. “We’ve decided that that’s too much busywork. If you want it, you can have it.”

The project was originally conceived as a publication of the 250 top quotations from the conversation books, but Albrecht soon realized that was too narrow a focus. “How can you tell what the top 250 are unless you translate everything?” He was also interested in what the conversations had to say about the premiere of the Ninth Symphony, which required a deeper dive into the material.

As a trial balloon, Albrecht began by translating Books No. 1 and 95, which are owned by the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn. Then after getting the go-ahead from his editor (“Good luck on the other 137”), he embarked on the rest, which the composer’s secretary, Anton Schindler, had acquired when Beethoven died. “Nobody thought they were worth anything,” Albrecht said. Schindler ended up selling them to the Berlin State Library in 1846 in exchange for a pension.

“There is a rumor that Schindler destroyed two-thirds of the books,” Albrecht said, “but that’s bogus. The books from 1820-1822 are missing, but that’s probably because they were in a trunk that bounced off the cart when Beethoven was traveling from Baden to Vienna.”

The mills of publishing grind slowly, especially where multiple owners of manuscripts and successions of editors are involved. After that initial conversation at the AMS meeting in 1996, it took until 2013 for the final legal agreements to be hammered out.

The task gets more complicated because of the level of detail. “In a normal book, I suppose you could get away with three or four subject headings per page,” Albrecht said. “In this case, if Beethoven made a shopping list of fifteen items, they all have to be indexed, including the tooth powder and the boot polish — he prefers a specific brand.”

Since the pages of the notebooks lack dates, much of Albrecht’s work involves establishing chronologies of events. “It takes a lot of sleuthing, but you just do it. It’s helpful that Schindler told us what the composer’s daily schedule was like, and another account in an 1823 interview is very close to Schindler’s.

“We know that Beethoven got up around 5 am, worked until the house started moving, and wrote letters before noon. Then he went out for dinner or coffee, ran errands, came home, read, and went to bed early. He was such a creature of habit that you can link events to dates in the conversation books.”

In a 2001 book, the Australian physician Peter J. Davies listed more than 40 contemporary references to Beethoven’s hearing problems. In the course of translating the conversation books, Albrecht has picked up more evidence, including notes from a visitor who reported that the composer understood him when he spoke into his left ear, and a random encounter in a coffee house with a hard-of-hearing person who asked Beethoven for advice about using mechanical devices like ear trumpets. (“By abstaining from using them, I have fairly preserved my left ear,” Beethoven wrote.)

In addition to an intriguing episode when Franz Liszt came to visit and played for Beethoven, Albrecht quotes a little recollection from the young Gerhardt Bruening, who grew up to become a prominent Viennese physician: “One time, at dinner at our apartment, one of my sisters let out a loud piercing shriek, and the fact that he still heard it made [Beethoven] so happy that he laughed out loud.”

One might think that Albrecht’s revelation of these cumulative bits of evidence would have shaken things up a bit in the classical music world, but old traditions die hard. A February article in The Guardian about his research did cause a bit of a stir, but as he said, “Thunderbolts have not descended on me yet.”

Albrecht noted that while the kind of research the conversation books require is painstaking and sometimes tedious, he’s careful not to let that come across when he writes about it. “I try to make it look as easy as possible,” he said, adopting a heavy Hungarian accent to quote some advice George Szell liked to give to The Cleveland Orchestra: “It must sound spontaneous, but it’s the result of me-tic-u-lous preparation.”

Published on ClevelandClassical.com April 27, 2020.

Click here for a printable copy of this article