by Daniel Hathaway

TODAY’S ALMANAC:

With some 1,128 surviving works, picking just a few to mark the composer’s passing is an exercise in futility. Two of them bookend his career in fascinating ways.

At the end of his life, Bach crowned his contrapuntal achievements with The Art of Fugue, a work that in a manuscript from the early 1740s contains twelve fugues and two canons on a single theme. By 1751, a year after the composer’s death, a revised edition had added two new fugues and two new canons as well as three pieces he may never have intended to include in the collection.

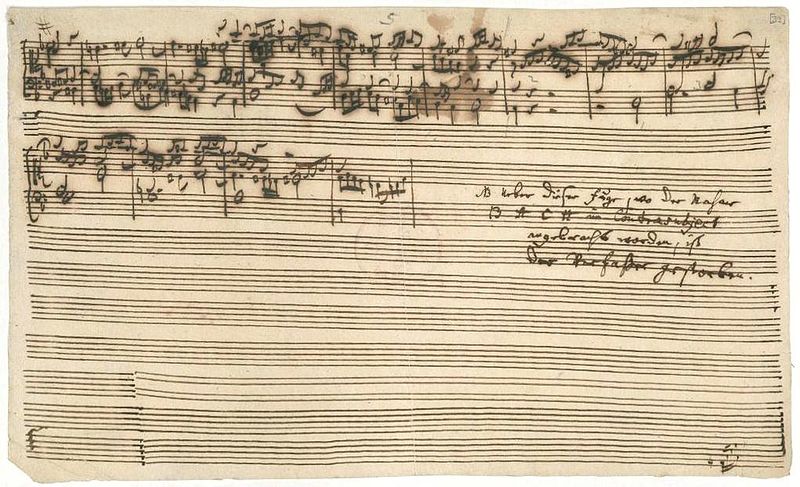

One of those three pieces is the autograph manuscript of an unfinished fugue that breaks off after measure 239 with a notation in the hand of C.P.E. Bach (above):

At the point where the composer introduces the name BACH in the countersubject to this fugue, the composer died.

That’s probably another of the musicological legends that makes classical music history so appealing to program commentators — scholars have pointed out that the composer’s failing eyesight would have made writing impossible well before 1750.

In any case, that errant fugue has come to be known as the final Contrapunctus in the collection. Some composers have set out to finish it, while various performers — there’s no instrumentation indicated — have decided to just let the piece unravel as a symbol of Bach’s unfinished business.

Click here to watch Musica Antiqua Köln take the latter course.

At the other end of his career, when Bach was about 22 and organist of the Church of Divi Blasii in Mühlhausen, he wrote the funeral cantata Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit (“God’s time is best”), a work that continues to hold a special place in his portfolio.

Click here to watch a performance of BWV 106 by Oberlin Baroque on Early Music America’s Young Performers Festival in Boston on June 17, 2011. The sound is a bit sub-par, but the performance is lovely. Or for a more atmospheric experience, watch Ton Koopman lead his Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra and Choir in a candlelit performance in a Gothic church (somewhere!)

Incidentally, on this date in 1850, the Bach-Gesellschaft was founded and embarked on the publication of the composer’s complete works, a monumental task that was completed with the publication of its 46th volume in 1900. Robert Schumann was among the founders.

NEWS BRIEFS:

Akron’s Dr. Kwame Scruggs, founder and director of the local nonprofit Alchemy, received the Innovation in Teaching Artistry Award from the Association of Teaching Artists on July 23. “The concept of Alchemy is to provide a safe environment and sense of community to assist in the development of adolescent males through mentoring and the telling, discussion, and analysis of mythological stories and fairy tales told to the beat of an African drum.” The organization has collaborated with the Akron Symphony, and was the backdrop for the feature-length documentary Finding the Gold Within (available on Amazon Prime).

The latest edition of Musical America’s One to One features a discussion with Susan Feder, program officer for the Arts and Culture Program of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the largest funder of the arts in the U.S. “She explains the recent shift in focus to social justice and how Mellon has been responding to what she describes as the ‘twin pandemics’ of COVID-19 and the killing of George Floyd, which has brought to the surface the urgency of inclusivity among all organizations, particularly in classical music. Recovery from both pandemics will be slow, she says; Mellon intends to assist with both.” Watch here.