by Tom Wachunas

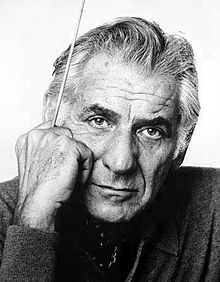

The evening commenced with his rarely performed Trouble in Tahiti, a one-act, two-character opera which Bernstein completed in 1951 while on his honeymoon with Chilean actress Felicia Cohn Montealegre. The timing was quite ironic if only because on one level the work is a cynical commentary on marriage. Additionally, Bernstein was acutely sensitive to America’s post-war euphoria in an increasingly affluent middle-class looking for an idyllic life in suburbia. His libretto for Trouble in Tahiti is a biting critique of materialism and a dour questioning of the American Dream itself.

Bernstein’s score is an ingenious melding of contrasting jazz and pop idioms of the day, rendered here by a pared-down ensemble that played nonetheless in a very large way, crisply embracing the story’s emotional and psychological tensions. It is the story, superbly directed here by Craig Joseph, of one day in the life of Sam, played by baritone Dan Boye, and Dinah, played by mezzo soprano Ellie Jarrett Shattles — a disillusioned, constantly arguing husband and wife. Beneath their veneer of carefree consumerism lies a bitter yearning to reclaim marital intimacy. Boye’s throaty vocals were well suited to his character’s chilling haughtiness tempered with moments of vulnerability. Shattles was riveting as the sassy, nagging wife given to episodes of tender self-examination and confession. In one scene, as she was alone watching a South Sea romance film called Trouble in Tahiti, she brought down the house with a hilarious aria that was both a tirade against the film’s silliness and a longing to escape into its magic. Meanwhile, a constant presence was the crackling jazz trio of Hilerie Klein Rensi, Scott Esposito, and George Milosh. Crooning in tight harmonies, and often sounding like goofy radio jingles about blissful family living, they were the equivalent of a mischievous Greek chorus relentlessly intoning sardonic comments.

The second half of the evening began with the full ensemble performing composer Eric Benjamin’s To LB: A Thank You Note. CSO Music Director Gerhardt Zimmermann has commissioned several works from Benjamin in the past — each noteworthy, to be sure — but I found this one to be the most beautiful to date. It’s an intensely personal and savory homage, inspired by Benjamin’s time spent with Bernstein in a master class at Tanglewood in 1989. Especially gratifying is how Benjamin has given us a moving remembrance of Bernstein’s spirit — the arc of his musical attitude, his religiosity — without falling into gratuitous stylistic imitation. Much of the music possesses an arresting sense of jaunty optimism and ever-emerging, triumphal adventure that at one point gives way to a sweetly contemplative melody, initiated by the piano, and blooming into a lushly romantic interlude before the breathtaking crescendo of the finale.

Benjamin’s marvelous piece was certainly a well-placed lead-in to the last work on the program, Bernstein’s groundbreaking Symphonic Dances from West Side Story. These collide-o-scopic dances comprise a veritable rollercoaster of gripping rhythms, textures, and moods — at once raw and refined, punchy and poetic, and by the end, achingly poignant. The orchestra’s performance was yet another spellbinding exposition of what makes the CSO such a compelling musical entity — a treasure-trove of rapturous aural power and clarity consistently balanced with genuinely alluring lyrical grace.

In this work, and for that matter throughout the entire evening, Zimmermann conducted with genuinely emotive authority. It was not an authority born of any autonomous bravado, but one clearly rooted in an understanding of what Bernstein once wrote about conducting: “Perhaps the chief requirement of [the conductor] is that he be humble before the composer; that he never interpose himself between the music and the audience; that all his efforts, however strenuous or glamorous, be made in the service of the composer’s meaning — the music itself, which, after all, is the whole reason for the conductor’s existence.”

Following the ebullient standing ovation for Symphonic Dances, Zimmermann, with a conspiratorial smile, asked the house, “How about one more?” whereupon he and his magnificent ensemble lit up the place again by launching another dazzling musical rocket in the form of Bernstein’s Overture to Candide.

As the enchanted audience exited Umstattd Performing Arts Hall, the air was palpably buzzing with folks exclaiming their delight and happily humming the infectious melodies they’d just heard. We had been summarily transported to…somewhere. That’s the joy of music.

Published on ClevelandClassical.com October 10, 2018.

Click heree for a printable copy of this article